Hong Kong J Psychiatry. 2006;16:65-70

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

I Karakaya, B Agaoglu, A Coskun, SG Sismanlar, NC Memik, O Yildizoc

Dr Isik Karakaya, MD, Kocaeli University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Kocaeli, Turkey.

Professor Belma Agaoglu, MD, Kocaeli University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Kocaeli, Turkey.

Professor Aysen Coskun, MD, Kocaeli University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Kocaeli, Turkey.

Dr Sahika G Sismanlar, MD, Kocaeli University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Kocaeli, Turkey.

Dr Nursu Cakin Memik, MD, Kocaeli University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Kocaeli, Turkey.

Dr Ozlem Yildizoc, MD, Kocaeli University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Kocaeli, Turkey.

Address for correspondence: Isik Karakaya, Cumhuriyet mah, Misir

sok, EK-AS Sit. A-Blok Daire: 7, Plajyolu-Izmit, Kocaeli, Turkey 41100.

Tel: (90 262) 226 9749; Fax: (90 262) 303 8003

E-mail: karakaya73@yahoo.com

Submitted: August 3 2006; Accepted: November 15 2006

Abstract

Objective: This study investigated high school students' symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder one and six months after a terrorist attack in Istanbul, Turkey on November 2003, and the relationship between the severity of the post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and the level of depression and anxiety.

Patients and Methods: 113 students filled in questionnaires and were assessed by use of Child Post-traumatic Stress Reaction Index, Children's Depression Inventory, and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children.

Results: We found high rates of post-traumatic stress reactions at the end of the first month (51.3%). The assessment of the students at the end of six months revealed that the symptoms of post- traumatic stress disorder tended to persist, although the total scores of Child Post-traumatic Stress Reaction Index were decreased. Post-traumatic stress disorder scores were significantly correlated with the scores of depression and anxiety at both assessments (p < 0.05).

Conclusion: These results indicate that post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms can be seen after a stressful event that was perceived as life-threatening by at least some of the children, even though the children did not experience major losses, injury, or ongoing disruption in the community.

Key words: Adolescent, Child, Stress disorder, Post-traumatic, Terrorism, Turkey

Introduction

Terrorism is defined by the US Department of Defense1 as "the calculated use of violence or threat of violence to inculcate fear intended to coerce or to intimidate govern- ments and societies in the pursuit of goals that are generally political, religious, or ideological". The goal of terrorism is not only to cause visible disaster, but also to inflict psycho- logical fear and intimidation at any time, during periods of peace or conflict. The few studies available on the subject of terrorism and children emerged in the aftermath of several terrorist events. An early descriptive study of the children kidnapped from their school bus in Chowchilla indicated that circumstances of extreme life threat could strongly affect child victims.2,3 State terrorism in Guatemala between 1981 and 1983,4,5 Scud missile attacks and terror- ist activities in Israel,6-8 bombing of the Alfred P. Murray Building in Oklahoma City9,10 and the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks11-13 are some of the events evaluated in stud- ies in the literature.

Children vary in their reactions to traumatic events.14 Some may suffer from worries and bad memories that dissipate with time and emotional support. Other children may be more severely traumatised and experience long-term problems. Children's emotional reactions may develop immediately after the trauma or may occur later. Acute stress disorder is the most common psychiatric disorder follow- ing traumatic events.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a reaction that may occur after a period of time.1, 2,10 PTSD rarely occurs in isolation. Children with PTSD may be more likely to have comorbid conditions because traumatic insults occur in developmental stages that are particularly sensitive to disruptions. Psychological disorders that commonly occur in conjunction with PTSD in children include depres- sion, feeling of guilt and hopelessness, acute stress disorder, and generalised anxiety disorder.2,10 Furthermore, depression and anxiety were reported to be prevalent among traumatised children, similar to the case in traumatised adults as depicted by other researchers.2,10,14

On November 20, 2003, a bomb exploded in Istanbul, Turkey; 14 people died and a greater number were injured in the attack. The students of a high school, not far from the site of attack, were in their classrooms during the explosion. No one was injured in the school. Telephone contact was established between school and parents, and parents learned that their children were safe. It took almost 3 hours for the parents to arrive at the school due to the chaos. During that time all the students and teachers were collected in the school garden that is the safest place at the school. Until the parents arrived at the school, none of the students were allowed to leave the school premises and nobody could come in. The children did not see the rescue operations but could hear them. The aim of this study was to investigate the frequency of PTSD symptoms, and the relationship between the severity of the PTSD symptoms and the level of depression and anxiety in Turkish children who experienced this attack.

Patients and Methods

Subjects

The study was carried out on sixth, seventh and eighth grade students of the index high school who were present at the time of the explosion. All of the students of sixth, seventh and eighth grade (n = 132) agreed to participate, and a total of 113 students completed the study. Nineteen students were absent at the time of second evaluation and were therefore excluded from the analyses. The students who completed the study neither had any direct physical exposure nor personally knew anyone killed or injured in the explosion.

Procedure

The clinical research team visited the school to coordinate and assist in data collection. Parental consent was obtained with the help of the school management prior to the commence- ment of the study and all students agreed to participate. There were 20-25 students in each class and subjects completed the scales in their classrooms on the same day. They were informed about the nature of the questionnaires before their administration, and a child and adolescent psychiatrist was available to answer any questions the students might have. The children did not undergo any treatment or counseling during the investigation period.

Instruments

The scales were given to the students 1 and 6 months after the bombing. The interviewers administered Child Post- Traumatic Stress Reaction Index (CPTSD-RI), Children's Depression Inventory (CDI), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAI-C), and an information form to the students. A 15-item information form prepared by the authors was designed to obtain information on demographic charac- teristics, trauma experience and history of previous trauma. The CPTSD-RI is a 20-item self-report scale designed to assess post-traumatic stress reactions of children between the ages of 6 and 16 following exposure to a broad range of traumatic events.15 The scale has been found to be valid in detecting PTSD according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Revised Third Edition (DSM-III-R) criteria.16 Items are rated on a 0-4 scale. Scores are classified as "mild" (total score of 12-24), "moderate" (25-39), "severe" (40-59) and "very severe PTSD reaction" (above 60).17 Inter-rater reliability is high, with Cohen kappa of 0.87 for inter-item agreement. CPTSD-RI was translated into Turkish and the validity and reliability of the Turkish version was evaluated by Erden et al.18 The Turkish version yielded significant positive correlations between DSM-IV PTSD criteria and CPTSD-RI scores (p < 0.001- < 0.01).18 The CDI is a 27-item self-report scale that measures cogni- tive and somatic symptoms of depression and is one of the most widely used scales in childhood depression. Each item lists three choices rated 0, 1, or 2 depending on the level of severity. In the current study, alpha values ranged from 0.61 to 0.91, which is consistent with other research.19 CDI was also translated into Turkish and the validity and reliability of the Turkish version was verified by Oy.20 STAI-C,21 also called "How I feel questionnaire", is an adaptation of the adult scale for school children. The inventory assesses global anxiety that varies with situations (state anxiety) and anxiety that is stable across time and situations (trait anxiety). The scale has high internal and test-retest reliabilities and moderate validity.22 STAI-C was translated into Turkish and the validity and the reliability of the Turkish version was tested by Ozusta.23

Statistical Analysis

The data were analysed by use of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 10.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). One-way analysis of variance was used to compare the difference between the mean scores of the three groups following the analysis of distribution within groups. When a significant difference was found, the groups were compared pair-wise to determine the origin of the difference. Student's t test or Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare the groups according to the distribution of the data. A p value lower than 0.05 was considered significant. Paired samples t test was employed to compare the scores obtained on first and second evaluations. Pearson correlation coefficient and partial correlation test were used to analyse the relationship between the scores of PTSD, depression and anxiety.

Results

Sample Characteristics

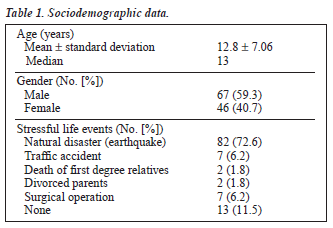

113 students were assessed. The age range was 12-14 years, with a mean of 12.8 years [standard deviation (SD), 7.06]. Sixty seven (59.3%) were males and 46 (40.7%) were females. All of the students were in their classrooms during the explosion, and no one was injured during the bombing. No previous trauma or crisis was reported by 11.5% of the students, whereas 88.5% had had various traumatic and/or crisis experiences (Table 1).

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms

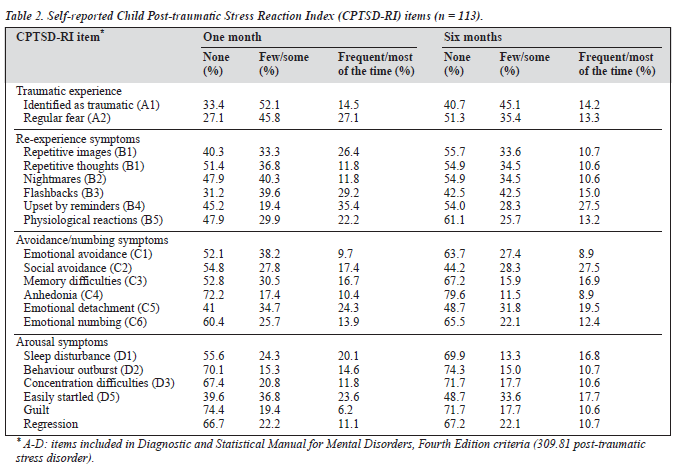

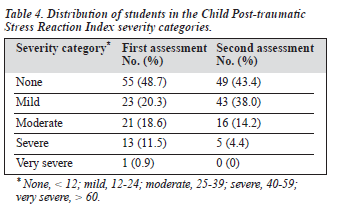

Fifty eight children (51.3%) reported post-traumatic stress reactions of at least mild severity: 23 (20.6%) reported mild, 21 (18.6%) moderate, 13 (11.5%) severe, and 1 (0.9%) very severe PTSD reactions during the first assessment. The mean CPTSD-RI score was 21.3 (SD, 1.25; range, 1-65). The most frequently reported symptoms in the first assessment were regular fear, repetitive images, fear of recurrence, emotional detachment, being easily startled, and being upset by reminders (Table 2).

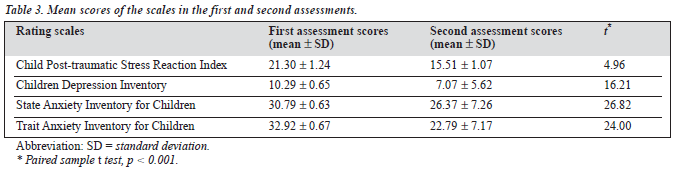

There was a statistically significant gender difference in the mean CPTSD-RI scores, with girls having significantly higher scores (p < 0.01). The mean scores of CDI, trait STAI-C and state STAI-C were 10.29 ± 0.65, 32.92 ± 0.67 and 30.79 ± 0.63, respectively (Table 3). The results of the first assessment revealed positive and significant correlations between the scores of PTSD and the level of depression (r = 0.60; p < 0.01), the level of trait anxiety (r = 0.71; p < 0.01), and the level of state anxiety (r = 0.52; p < 0.01). After controlling for state and trait anxiety scores, correla- tion analysis revealed a weak but significant positive corre- lation between the levels of PTSD and depression (r = 0.20; p < 0.05). If the depression scores were controlled for, a moderately positive correlation between trait anxiety levels and PTSD scores (r = 0.52; p < 0.05), and a weak positive correlation between state anxiety levels and PTSD scores (r = 0.20; p < 0.05) were found (Table 2).

At the 6-month follow-up assessment, 64 children re- ported post-traumatic stress reactions, of whom 43 (38.0%) had mild, 16 (14.2%) moderate, and 5 (4.4%) severe PTSD symptoms. None of the children had very severe post- traumatic stress symptoms. The mean CPTSD-RI score was 15.51 (SD, 1.07; range, 1-52; 95% confidence interval, 15.32-15.70). The most frequently reported symptoms were fear of recurrence, emotional detachment, being easily startled, being upset by reminders, and social avoidance (Table 2). No gender difference was observed in the mean CPTSD-RI scores. The mean scores of CDI, trait STAI-C and state STAI-C were 7.07 ± 5.62, 26.37 ± 7.26, and 22.79 ± 7.17, respectively (Table 3). According to the rating scales at 6 months, there were significant correlations between the scores of PTSD and the level of depression (r = 0.36; p < 0.01), and the levels of trait (r = 0.28; p < 0.01) and state anxiety (r = 0.25; p < 0.01). In partial correlation analysis, a positive correlation was still detected between depression and PTSD scores (r = 0.22; p < 0.05), controlling for state and trait anxiety levels. However, when depression scores were controlled for, significant correlation between levels of PTSD and state and trait anxiety detected at 1 month (r = 0.06; p = 0.56) disappeared at 6 months (r = 0.11; p = 0.24) [Table 3].

When comparing the severity of the symptoms of PTSD observed in the students who had no previous experience of a traumatic event or crisis (n = 13), those who had one previous experience of a traumatic event and/or crisis (n = 35) and those who had more than one previous experience of traumatic event (n = 65), the differences between the groups were statistical- ly significant at both assessments (F = 8.71, p < 0.001 and F = 4.91, p = 0.009, respectively). After analysis by Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) test, this difference was found attributable to the students who had more than one traumatic event (chi-squared = 16.58; p = 0.001 versus chi- squared = 13.19; p = 0.001). The students who endured more than one traumatic event had higher CPTSD-RI scores than the others. We did not find any significant difference in the mean scores of the students who had no experience of a traumatic event and those who had one traumatic event.

A statistically significant decrease in the total CPTSD- RI scores was detected (Table 3). The frequency of mild PTSD reactions was found to be increased at 6 months (Table 4). In the second assessment, the severity of PTSD symptoms was unchanged in 50 students (44.3%), whereas it decreased in 52 (46.0%), and increased in 11 (9.7%).

Discussion

In this study, we found high rates of post-traumatic stress reactions among teenage middle school students who ex- perienced a terrorist attack. The students were assessed one and six months after the terrorist attack in order to evaluate the effect of time on PTSD symptomatology in early adolescence. Twenty three students (20%) had mild and 35 (31%) had moderate to severe PTSD symptoms at the 1-month assessment. At the 6-month follow-up assessment, 43 students (38.0%) had mild and 21 (18.6%) had moderate to severe symptoms of PTSD. The majority of studies refer to young people who experienced natural catastrophic events such as floods (with prevalence of 37% at post-flood and 7% at 17 years later),24 hurricanes (short-term prevalence of 3-9%)25,26 and earthquakes (rates varying from 37% to 91%).27 The frequency of PTSD in children who en- countered terrorist activities ranged between 28% and 50%.6,7,9,13,28,29 Pynoos et al16 studied children who had lived through a sniper attack at their school. Nearly 40% were found to have moderate to severe PTSD. Fourteen months later, Nader et al30 assessed the same children and reported that 74% of those most severely affected by being in the playground at the time of the incident still reported high levels of PTSD, while 19% of the children who did not witness the incident reported some degree of PTSD. Thabet and Vostanis31 assessed Palestinian children who experienced war traumas. PTSD reactions of at least mild intensity were observed in 72.8% of the sample, while 41% reported moderate/severe PTSD reactions.

The total scores of CPTSD-RI of the female students and of those who had more than one previous trauma experience were found to be higher at both assessments in this study. Inconsistent findings exist regarding gender differences in the development of PTSD symptoms after exposure to any trauma. Some investigators reported no gender difference,32,33 whereas others suggested that there were more severe and longer symptoms of PTSD in girls.34 Cumulative traumas were also suggested to be associated with more severe and longer symptoms of PTSD.35

The most frequently reported symptoms at both assess- ments were fear of recurrence of the trauma, emotional detachment, being easily startled, being upset by reminders and avoidance of situations that reminded the trauma. In regards to the responses of the adolescents (ages 12-18), our findings were consistent with the literature.36 Studies have established that the diagnostic criteria of PTSD in children and adolescents were not totally met and that only some of the symptoms were present.37,38

Yule and Udwin39 and Goenjian et al40 reported positive correlations between the levels of PTSD, depression and anxiety. We found that the PTSD scores were significantly correlated with the scores of depression and anxiety at both assessments. It is known that especially PTSD and major depressive disorder-dysthymia are frequently seen together in children and adolescents. Several authors have hypothesised that PTSD precedes and predisposes to the onset of major depressive disorder rather than the reverse.41 On the other hand, some authors suggested that previous psychiatric illness was related to the development of PTSD symptoms.15,17 However, based on the results of our study, we could not answer the question whether anxiety and depressive symptoms caused a tendency to PTSD or devel- oped secondary to PTSD.

Longitudinal studies have reported that the symptoms of PTSD may last for years.27,42,43 Children who develop PTSD reactions after exposure to terrorism often continue to manifest symptoms of PTSD over time, even though terrorist activities or threats are no longer present.44,45 The assessments of the students at 6 months revealed that the symptoms of PTSD persisted although the total CPTSD-RI scores were found to be decreased. In the second assessment, it was found that the severity of PTSD symptoms reported during the first assessment did not change in 44.3%, whereas it was found to be decreased in 46.0%, and increased in 9.7% of students. The finding that PTSD symptoms in some students did not change or increased at second assessment might be attributed to various factors, such as media exposure or emotional contagion from parents or peers.

Our study had several limitations. Children's family char- acteristics and previous psychiatric history, which might play an important role in the development and the chronicity of the symptoms of PTSD, were not evaluated. Another limi- tation was the absence of assessment of global functioning or a clinical interview in addition to the CPTSD-RI in order to establish whether children met all the criteria for PTSD according to DSM-IV. Also, because the scale was used to assess post-traumatic stress reactions following a specific trauma, we were unable to include any type of control group in our study.

These results indicated that PTSD symptoms could be seen after a stressful event that was perceived as life-threatening by at least some of the children, even if the children did not experience major losses, injury and there was no ongoing disruption in this community.

References

- US Department of Defense. Department of Defense Combating Ter- rorism Program (Department of Defense Directive Number 2000.12). Available from: www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB55/2000.12.pdf

- Terr LC. Children of Chowchilla: a study of psychic trauma. Psychoanal Study Child. 1979;34:547-623.

- Terr LC. Chowchilla revisited: the effects of psychic trauma four years after a school bus kidnapping. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:1543-50.

- Melville MB, Lykes MB. Guatemalan Indian children and the socio- cultural effects of government-sponsored terrorism. Soc Sci Med. 1992; 34:533-48.

- Miller KE. The effects of state terrorism and exile on indigenous Gua- temalan refugee children: a mental health assessment and an analysis of children's narratives. Child Dev. 1996;67:89-106.

- Laor N, Wolmer L, Mayes L, et al. Israeli preschoolers under the Scud missile attacks. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:416-23.

- Laor N, Wolmer L, Mayes L, et al. Israeli preschool children under Scuds: a 30 month follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:349-56.

- Wolmer L, Laor N, Cicchetti DV. Validation of the Comprehensive Assessment of Defense Style (CADS): mothers' and children's re- sponses to the stresses of missile attacks. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189: 369-76.

- Pfefferbaum B, Nixon SJ, Tucker RM, et al. Posttraumatic stress re- sponses in bereaved children following the Oklahoma City bombing. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;39:1372-9.

- Pfefferbaum B, Seale T, McDonald N, et al. Posttraumatic stress two years after the Oklahoma City bombing in youths geographically dis- tant from the explosion. Psychiatry. 2000;63:358-70.

- Hoge CH, Pavlin JA. Psychological sequelae of September 11. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:443-5.

- Schlenger WE, Caddell JM, Ebert L, et al. Psychological reactions to terrorists attacks. Findings from the national study of Americans' reac- tions to September 11. JAMA. 2002;288:581-8.

- Susser E, Jackson H, Hoven C. Terrorism and mental health in school: the effects of September 2001 on New York City schoolchildren. Avail- able from: www.fathom.com/feature/19050.

- Yehuda R, Mc Farlane AC, Shalev AY. Predicting the development of posttraumatic stress disorder from the acute response to a traumatic event. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;62 (Suppl 17):23-8.

- Frederick CJ. Children traumatized by catastrophic situations. In: Eth S, Pynoos RS, editors. Post-traumatic stress disorder in children. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1985.

- Pynoos RS, Frederick C, Nader K, et al. Life threat and posttraumatic stress in school-age children. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:1057-63.

- Goenjian A, Pynoos R, Steinberg A, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in children after the 1988 earthquake in Armenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1174-84.

- Erden G, Kilic EZ, Uslu RI, Kerimoglu E. The validity and reliability study of the Turkish version of child posttraumatic stress reaction index. Çocuk ve Gençlik Ruh Sagligi Dergisi. 1999;6:143-9.

- Kovacs M. Children's Depression Inventory Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi- Health Systems; 1992.

- Oy B. Children's Depression Inventory: A study of reliability and validity. Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi. 1991;2:132-6.

- Spielberger CD, Edwards CD, Montuori J, Lushene R. State-Trait Anxi- ety Inventory for Children. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1973.

- Carey MP, Faulstich ME, Carey TC. Assesment of anxiety in adolescents: concurrent and factorial validities of the Trait anxiety scale of Spielberger's State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for children. Psychol Rep. 1994;5:331-8.

- Ozusta S. State-trait anxiety inventory for children: A study of reliabil- ity and validity. Turk Psikoloji Dergisi. 1995;10:32-44.

- Green BL, Grace M, Vary MG, Kramer T, Gleser GC, Leonard A. Chil- dren of disaster in the second decade: A 17-year follow-up of Buffalo Creek survivors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:71-9.

- Garrison CZ, Bryant ES, Addy CL, Spurrier PG, Freedy JR, Kilpatrick DG. Post-traumatic stress disorder in adolescents after Hurricane Andrew. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1193-201.

- Shannon MP, Lonigan CJ, Finch AJ, Taylor CM. Children exposed to disaster: Epidemiology of posttraumatic symptoms and symptom profile. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:80-93.

- Pynoos RS, Goenlian A, Tashjian M, et al. Posttraumatic stress reac- tions in children after the 1988 Armenian Earthquake. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:239-47.

- Kinzie JD, Sack WH, Angell RH, Manson S, Rath B. The psychiatric effects of massive trauma on Cambodian children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1986;25:370-6.

- Laor N, Wolmer L, Cohen D. Mother's functioning and children's symp- toms 5 years after a Scud missile attack. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158: 1020-6.

- Nader K, Pynoos R, Fairbanks L, Frederick C. Children's PTSD reac- tions one year after a sniper attack at their school. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1526-30.

- Thabet AA, Vostanis P. Post-traumatic stress reactions in children of war. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 1999;40:385-91.

- Burton D, Foy D, Bwanausi C, et al. The relationship between trau- matic exposure, family dysfunction, and posttraumatic stress symp- toms in male juvenile offenders. J Trauma Stress. 1994;7:83-93.

- Sack WH, Clarke GN, Seeley J. Posttraumatic stress disorder across two generations of Cambodian refugees. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1160-6.

- Helzer JE, Robins LN, McEnvoy L. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the general population. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1630-4.

- Mollica RF, Poole C, Son L, Murray CC, Tor S. Effects of war trauma on Cambodian refugee adolescents' functional health and mental health status. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1098-106.

- Weisenberg M, Schwartzwald J, Waysman M, Solomon Z, Klingman A. Coping of school-age children in the sealed room during the Scud mis- sile bombardment and postwar stress reactions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:462-7.

- Cohen JA, Mannaririno AP. Factors that mediate treatment outcome of sexually abused preschool children: six and 12-monh follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:44-51.

- Pfefferbaum B. Posttraumatic stress disorder in children: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1503- 11.

- Yule W, Udwin O. Screening child survivors for posttraumatic stress disorder: Experiences from the 'Jupiter' sinking. Br J Clin Psychol. 1991;30:131-8.

- Goenjian AK, Pynoos RS, Steinberg AM, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in children after the 1988 earthquake in Armenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1174-84.

- AACAP Official Action. Summary of the Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with posttrau- matic stress disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37: 997-1001.

- Almqvist K, Brendell-Farsberg M. Refugee children in Sweden: post- traumatic stress disorder in Iranian preschool children exposed to or- ganized violence. Child Abuse Negl. 1997;41:450-7.

- Desivilya H, Gal R, Ayalon O. Long term effects of trauma in adolescents: comparison between survivors of a terrorist attack and control counterparts. Anxiety Stress Coping. 1996;9:1135-50.

- Pfefferbaum B, Gurwitch R, McDonald N, et al. Posttraumatic stress among young children after the death of a friend or acquaintance in a terrorist bombing. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:386-8.

- Koplewicz HS, Vogel JM, Solento MV, et al. Child and parent response to the 1993 World Trade Center Bombing. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15: 77-85.