Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2006;16:87-91

Original Article

A Preliminary Stduy of the Effects of Music Therapy on Agitation in Chinese Patients with Dementia

音樂治療對華裔痴呆患者激越行為的初步研究成效

RWK Tuet, LCW Lam

脫永基、林翠華

Mr RWK Tuet, MSc, Chung Shak Hei Home for the Aged, Hong Kong, China.

Prof LCW Lam, MD, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, New Territories, Hong Kong, China.

Tel: (852) 2607 6026; Fax: (852) 2667 1255; E-mail: cwlam@cuhk.edu.hk

Submitted: 17 October 2006; Accepted: 5 January 2007

Abstract

Objective: Agitation was common in patients suffering from moderate to severe dementia, for which music therapy is one of the commonly used non-pharmacological interventions. This preliminary report addresses the effectiveness of music therapy for demented patients residing in a local care setting for the elderly.

Patients and Methods:This was a crossover study. Fourteen patients with dementia exhibiting at least one type of agitated behaviour were recruited and divided into 2 groups. For 3 weeks, 1 group received music therapy and the other usual care with no special intervention. Thereafter, the 2 groups were crossed over with respect to the active and control interventions for further 3 weeks. Behaviour disturbances were measured by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory and the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory. Assessments were conducted before attending (pre-music or pre-control therapy); just after completion of music or control therapy (end-music or end-control therapy) and 3 weeks after music therapy (post-music therapy).

Results: There were significant reductions of total Neuropsychiatric Inventory and Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory scores at the end-music therapy period (Wilcoxon signed rank tests, p < 0.001). Similar reductions were not found after usual care (end-control period). No lasting effects were observed after withdrawal of music therapy for 3 weeks (pre-music therapy vs post-music therapy; Wilcoxon signed rank tests, p = not significant).

Conclusion:These preliminary results suggest that music therapy may have positive effects on behavioural disturbances manifested by demented elders. Although the effects were not persistent, music therapy may be considered for further research as a continuous means of reducing agitation in care settings for the older persons.

Key words: Dementia; Music therapy; Psychomotor agitation

摘要

目的:激越行為在中度至嚴重痴呆患者中非常普遍,音樂治療是其中一項非藥物治療方法。這初步研究報告探討音樂治療對居於院舍、患有痴呆的長者激越行為的效果。

患者與方法:是項病例對比研究共14名至少患有一種激越行為的痴呆患者參與。患者分為兩組,第一組首先接受三星期音樂治療,另一組則沒有接受特別治療。三星期後,兩組互相對換。研究探用神經精神料問卷(NPI)及Cohen-Mansfield激越行為量表(CMAI) 計算行為困擾程度,並幸福患者進行三個階段(音樂治療前、剛完成音樂治療,及音樂治療結束後三星期)的評估。

結果:NPI及CMAI的總分在剛完成音樂治療後明顯下降(Wilcoxon signed rank test, p < 0.001 ) 而對照組在這兩方面則沒有明顯下降。音樂治療完結三星期後,激越行為回復音樂治療前水平(音樂治療前對比音樂治療結束後三星期. Wilcoxon signed rank test, p = not significant) 。

結論:這項初步研究顯示,音樂治療可能對年長痴呆患者的行為困擾有正面影響。雖然其效果未能在療程完結後持續,但作為可改善長者在護理環境下激越行為的漸進方法,應考慮對音樂治療作更深入的探討。

關鍵詞:痴呆、音樂治療、激越行為

Introduction

Dementia is a debilitating and irreversible neurological disease and as it progresses, behavioural and psychological social disturbances (BPSD) increase.1 The most challenging behaviours can be agitation.2 Behavioural and psychological disturbances are an integral part of the disease process and present severe problems to patients and their caregivers. For one-third of community-dwelling older persons with dementia, the severity of BPSD is clinically significant,3 and increases to almost 80% for persons with dementia living in institutions.4 Despite a high prevalence, the conceptual framework of agitation in dementia has not been consistently defined. Cohen- Mansfield et al5,6 proposed that agitation may be a construct of interrelated behaviour problems, rather than a unified concept. Agitated behaviours can be broadly divided into physically non-aggressive with / without disturbing elements, physically aggressive, and verbally aggressive behaviours. The frequency of agitated behaviours is positively related to the level of cognitive impairment. An explanatory framework has been proposed. The Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold model7 proposed that as the level of dementia increases, the threshold for baseline agitated behaviour decreases. The amount and intensity of stressors contribute to the overall risk for agitated behaviour. This model also predicts that despite impaired brain function, baseline desirable behaviour can be maximised by modifying environmental stimuli and controlling for factors that correlate with the perception of stressors.8 As music therapy (MT) may be an effective calming agent, its potential for reducing agitation in demented patients deserves further exploration.

According to the American Music Therapy Association’s website, MT is the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualised goals within a therapeutic relationship.9 It has been used as a non-pharmacological intervention for patients of all ages in a variety of clinical practice settings. Elderly people with dementia are especially susceptible to the incongruence created by unfamiliar environments that may result in negative psychosocial outcomes.10 Elderly with dementia may evoke memories encoded with familiar environmental cues, such as old pictures and familiar music.11,12 Since elderly with dementia are impaired in terms of new learning, maximising the sense of familiarity may enhance their functional abilities,13 and could even stimulate remote memories associated with positive feelings.14 A previous report indicated that the areas of the brain that respond to music are the last to deteriorate in dementia and suggested that music may be one form of communication that remains preserved in such individuals.15 Memory for familiar music may prompt motor activity or memory recall, and be used as a stimulus and / or catalyst for reminiscences of forgotten memories.16,17 Music that elicits positive memories possesses a soothing effect and may reduce agitation in older people with dementia.18 According to recent studies on the effects of MT, most reported reduced agitated, aggressive or disruptive behaviours during and after the MT session.19-22

One study suggested that music-based exercise programmes have beneficial effects on cognition among patients with moderate to severe dementia.23

As different cultures have different perceptions about music, this study aimed to explore the effects of group MT on Chinese subjects with dementia complicated by agitated behaviour. In this preliminary study, music was viewed as a noninvasive intervention. The effects of planned MT sessions on BPSD among agitated, elderly subjects with dementia were therefore evaluated and potential implications discussed.

Methods

Subjects and Settings

Sixteen residents were recruited from 2 residential homes and 1 day-care centre for the elderly in Hong Kong. They included 13 women and 3 men, aged 84 to 101 years. The diagnosis of dementia was based on the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR).24 The CDR was performed by the principal investigator, who was an occupational therapist (OT) with certified training on its administration. First, only subjects with an impairment level between 2 (moderate) and 3 (severe) were included. Second, they had to manifest at least one type of agitated behaviour per week: aggressiveness or physically non-aggressive but with verbal and / or vocal agitation. Third, subjects could not be totally deaf or have severe hearing problems and had to be able to listen and respond to simple conversations by the staff. Fourth, the subject’s family members or guardians had to consent to their subjects’ participation in the study. Ethics approval was granted from the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Design and Procedure

A trial with crossover design was adopted. The 16 subjects were equally divided into 2 groups. The first was submitted to MT sessions for 3 weeks and the second received usual care (UC, control therapy) over that period. Three weeks after termination of the music sessions, the second group was submitted to MT sessions and the first group received UC. The MT sessions took place in groups inside the respective centres, 3 times weekly. Each session lasted 45 minutes during the late afternoon (when the ‘peak’ for agitated behaviour usually occurs), and was conducted by the OT and 2 therapist assistants. The content of each session was standardised and divided into an introduction (to greet and know each other), instrumental music (use of simple musical instruments to follow songs), and exercises with music (e.g. kicking balls with music). The OT recorded the performance of each subject before and at the end of each MT or control session and 3 weeks later. For the control sessions, no special intervention was administered.

Content of the Music Therapy

A pilot study to identify the suitable piece of music and standardise the logistics of the group session was carried out with 6 patients, before the actual programme began. The exploratory session included listening and singing songs without a musical instrument, listening to songs accompanied by different kinds of musical instruments, playing exercises when listening to songs. Examples of pieces chosen included relaxing western and Chinese traditional music. The observers recorded the reaction and performance of each subject.

Chinese folk music songs were identified as the most stimulating. Two subjects could sing along whilst the songs were played. For the playing of musical instruments, some were placed on the table for the subjects to exercise free choice, with the assistance of staff. However, 2 subjects changed their instruments frequently during the sessions. In the later part of the MT sessions, a balloon was placed on the table to facilitate free bodily movements.

Assessment Tools

The CDR24 is a semi-structured clinical rating of the severity of dementia. The severity of cognitive impairment was rated by evaluation of 6 areas of cognition and functioning, which included: orientation, memory, judgement / problem- solving, community living, hobbies and habits, as well as personal care. A score of 0 indicated normal cognition, a score of 1 or more indicated clinical dementia (1: mild; 2: moderate, 3: severe).

The Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory5,6 (CMAI) is a 29-item caregiver-rated scale, developed for use in nursing homes in order to record the frequency of agitated behaviours over a 2-week period. Factor analysis revealed 3 syndromes of agitated behaviour: physically aggressive, physically non-aggressive, and verbally agitated. The CMAI evaluates the frequency of agitated behaviours. The total agitation score was calculated by summing the scores for the individual behaviours.

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory25,26 (NPI) is a caregiver-rated semi-structured interview to identify the pattern and profiles of neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with neurodegenerative disorders. Ten neuropsychiatric symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, agitation, depression, apathy, euphoria, disinhibition, anxiety, irritability, aberrant motor behaviours), and 2 vegetative symptoms (night-time behaviours and appetite disturbances) were evaluated. The total NPI score was calculated by multiplying the scores of the frequency and severity of each symptom, and summing the subtotals. In this study, a Chinese version of NPI nursing home version was used.

Assessment Schedule

Nursing staff of the care and attention homes collected the data. Before the programme started, a training session on the use of CMAI and NPI was given to all involved nursing staff. Responsible nursing staff collected data at 3 time- points: at baseline before any MT sessions began (pre-), in the week after the sessions ended (end-), and 3 weeks after the sessions (post-). If a patient was absent on more than 4 sessions, whether due to refusal, hospitalisation or home- leave, that individual was excluded.

Statistical Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows version 13.0 was used for the analyses. Non-parametric tests were used to determine whether there were any significant group (MT & UC) differences in behavioural measures (NPI and CMAI scores) at the baseline (pre-), upon completion of MT (end-), and 3 weeks after MT has completed (post-). The changes of total NPI and CMAI scores were compared between the MT and UC periods using Mann-Whitney U tests. Statistical significance was set at a level of 0.05.

Results

One subject withdrew from the study, having refused to continue, and 1 was withdrawn as she was hospitalised. Thus the total number of patients who completed the study was 14; 12 women and 2 men, aged from 80 to 101 (mean [SD], 90 [5.5]; median, 91) years. Twelve subjects were diagnosed as Alzheimer’s disease and 2 were diagnosed as having vascular dementia. Eleven subjects had not received any education, 2 had received primary education, and 1 had received secondary education. The Mini-Mental State Examination scores ranged from 0 to 21.

Effects of Music Therapy on Total Neuropsychiatric Inventory Scores

The total NPI scores before MT (pre-NPI) ranged from 6 to 57 (mean [SD], 25.2 [16.4]). The NPI scores after the MT (end-NPI) ranged from 3 to 24 (9.6 [6.3]). Significant differences in NPI scores were identified between the pre- and end-NPI scores in the MT group (Wilcoxon signed rank test, z = 3.73, p < 0.001). Compared to the baseline, there were no significant differences in the total NPI scores 3 weeks after the MT (post-NPI) [range, 6-54; mean (SD), 25.1 (15.7)] (Wilcoxon signed rank test, z = 1.62, p = 0.11). In the UC group, there was no significant change in total NPI scores from pre-NPI (6-55; 25.5 [16.4]) to end-NPI (6- 55; 25.2 [16.2]) [Wilcoxon signed rank test, t = 1.41, p = 0.16].

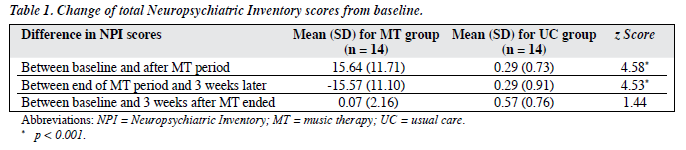

The Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare the difference of NPI scores in the MT and UC groups. There were no significant differences in the change of NPI scores between the baseline and 3 weeks after the MT. There was a significant drop in the NPI scores immediately after the MT (Mann-Whitney U test, z = 4.58, p < 0.001), but not following UC (end-control therapy). Details are summarised in Table 1.

Effects of Music Therapy on Total Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory Scores

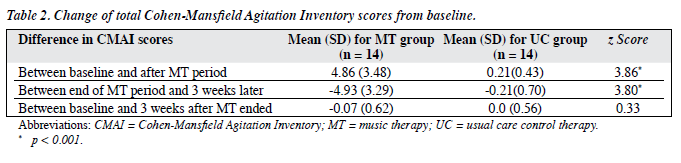

As for the pre-CMAI score, it ranged from 0 to 29 (mean [SD], 12.4 [8.5]). After the MT sessions (end-CMAI), the score ranged from 0 to 16 (7.5 [5.3]) [Wilcoxon signed rank test, z = 3.42, p = 0.001]. The 3-week post-CMAI scores (0-28, [12.4 (8.3)]) were not significantly different from those at baseline (pre-CMAI) [Wilcoxon signed rank test, z = 0.33, p = 0.74]. The CMAI scores of the UC group remained stable with no significant change being noted throughout the study period (Wilcoxon signed rank tests between pre-CMAI, end-CMAI and post-CAMI scores, p = not significant). Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to compare the difference in CMAI scores between MT and UC groups. There was no significant change in total pre-CMAI scores and 3 weeks after completion of MT or UC (post-CMAI) [Mann-Whitney U test, z = 0.33, p = 0.74]. There was also a significant reduction of end-CMAI scores in those receiving MT (z = 3.86, p < 0.001); similar reductions in CMAI scores were not found in the UC group. Details are shown in Table 2.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that MT may be beneficial in reducingbehaviouralproblemsdisplayedbydementedelderly, though there was no clear theory to explain how it may affect physical and psychological responses. For demented elderly patients, music may be helpful in re-orientation, rebuilding social links, eliciting memory, and raising their morale.18

It seemed that there was no continuing effect following MT; patients with dementia elicited similar behavioural problems again after 3 weeks. This finding was similar to that reported by Ashida27 with no lasting effect observed after the sessions ended. The Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold model proposes that agitation may be reduced by modifying environmental stimuli and controlling for factors that correlate with perception of stressors.7 Accordingly, if MT ceases, the modifying environmental stimuli also cease and agitated behaviour recurs.

The results of this study were limited by its sample size, and because patients were chosen from local health care settings. In these settings patients encounter multiple medical problems and frequent hospitalisation. The small sample size precluded further analyses of the effects of MT on individual BPSD scores. It would also have been of interest to explore the effects on non-agitated behaviours commonly found in demented elders. To obtain a more representative result, a larger randomised controlled trial on MT was needed. A second limitation was that there was no control over psychotropic medications used during the study period. Possible interactions between music intervention and medication effects were not examined. Possible effects of music as an adjunctive therapy for pharmacological interventions should be a target in future studies. Third, the subjects involved were mostly suffering from moderate to severe dementia, and hence findings may not be generalised to persons with milder forms of dementia. Fourth, group sessions were held in 2 different settings. Differences in settings may contribute to the variability in the way the intervention was implemented and the way subjects respond to the treatment, thus leading to increased variability in outcomes, though having only 1 OT implementing the MT might have minimised discrepancies. Fifth, due to limitation in resources, the raters were staff at the respective centres and were not blinded to the intervention schedule, which may introduce biases in assessment. However, as our results suggesting that MT offered a transient effect on BPSD were consistent with other previous reports in the literature, they were likely to have been reliable.

Until more definitive treatments for demented elderly become available, different strategies should be explored to minimise the impact of the disease on daily activities. Our preliminary results suggest a positive effect of MT on behavioural disturbances manifested by demented elders. Although the effects were not persistent, MT may be considered for further research as another means of reducing agitation in care settings for older persons. The role of MT (including different kinds of MT) on other medical diagnoses such as stroke and Parkinsonism should also be explored.

Acknowledgements

The authors wanted to express their thanks to the therapy assistants for their help in conducting the MT sessions, as well as the participants and their caregivers for their kind consent and cooperation throughout the study period.

References

- Gotell E, Brown S, Ekman SL. Caregiver singing and background music in dementia care. West J Nurs Res 2002;24:195-216.

- Smith AG. Behavioral problems in dementia. Strategies for pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic management. Postgrad Med 2004;115:47-52,55-6.

- Lyketsos CG, Sheppard JM, Rabins PV. Dementia in elderly persons in a general hospital. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:704-7.

- Margallo-Lana M, Reichelt K, Hayes P, Lee L, Fossey J, O’Brien J, et al. Longitudinal comparison of depression, coping, and turnover among NHS and private sector staff caring for people with dementia. BMJ 2001;322:769-70.

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Rosenthal AS. A description of agitation in a nursing home. J Gerontol 1989;44:M77-84.

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Rosenthal AS. Dementia and agitation in nursing home residents: how are they related? Psychol Aging 1990;5:3-8.

- Hall GR, Buckwalter KC. Progressively lowered stress threshold: a conceptual model for care of adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 1987;1:399-406.

- Hall GR, Buckwalter KC, Stolley JM, Gerdner LA, Garand L, Rideway S, et al. Standardized care plan. Managing Alzheimer’s patients at home. J Gerontol Nurs 1995;21:37-47.

- Johnson CM, Geringer JM, Stewart EE. A descriptive analysis of internet information regarding music therapy. J Music Ther 2003;40:178-88.

- Mirotznik J, Ruskin AP. Inter-institutional relocation and its effects on psychosocial status. Gerontologist 1985;25:265-70.

- 1 Knight RG. Controlled and automatic memory process in Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex 1998;34:427-35.

- Son GR, Therrien B, Whall A. Implicit memory and familiarity among elders with dementia. J Nurs Scholarsh 2002;34:263-7.

- Camberg L, Woods P, McIntyre K. SimPress: a personalized approach to enhance well-being in persons with dementia. Volicer L, Bloom- Charette L, editors. In: Enhancing the quality of life in advanced dementia. Brunner/Mazel, Philadelphia; 1999:126-40.

- Sung HC, Chang AM. Use of preferred music to decrease agitated behaviors in older people with dementia: a review of the literature. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:1133-40.

- Crystal HA, Grober E, Masur D. Preservation of musical memory in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neruosurg Psychiatry 1989;52:1415-6.

- Cuddy LL, Duffin J. Music, memory, and Alzheimer’s disease: is music recognition spared in dementia, and how can it be assessed? Med Hypotheses 2005;64:229-35.

- Clair AA. The effect of singing on alert responses in persons with late stage dementia. J Music Therap 1996;33:234-47.

- Gerdner LA. Effects of individualized versus classical “relaxation” music on the frequency of agitation in elderly persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Int Psychogeriatr 2000;12:49-65.

- Clark ME, Lipe AW, Bilbrey M. Use of music to decrease aggressive behaviors in people with dementia. J Gerontol Nurs 1998;24:10-7.

- Jennings B, Vance D. The short-term effects of music therapy on different types of agitation in adults with Alzheimer’s. Activities, Adaptation and Aging 2002;26:27-33.

- Remington R. Calming music and hand massage with agitated elderly. Nurs Res 2002;51:317-23.

- Brotons M, Marti P. Music therapy with Alzheimer’s patients and their family caregivers: a pilot project. J Music Ther 2003;40:138-50.

- Van de Winckel A, Feys H, De Weerdt W, Dom R. Cognitive and behavioral effects of music-based exercises in patients with dementia. Clin Rehabil 2004;18:253-60.

- Morris JC. Clinical dementia rating: a reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int Psychogeriatr 1997;9 Suppl 1:173-6.

- Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994;44:2308-14.

- Leung VP, Lam LC, Chiu HF, Cummings JL, Chen QL. Validation study of the Chinese version of the neuropsychiatric inventory (CNPI). Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:789-93.

- Ashida S. The effect of reminiscence music therapy sessions on changes in depressive symptoms in elderly persons with dementia. J Music Ther 2000;37:170-82.

Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2006, Vol 16, No.3 91