Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2007;17:131-8

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr LW Choy, MBBS, MRCPsych (UK), FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

Dr ELW Dunn, MBBS, MRCPsych (UK), FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr LW Choy, Department of Psychiatry, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital. 3 Lok Man Road, Chai Wan, Hong Kong, China.

Tel: (852) 2595 4338; Fax: (852) 2595 9721; E-mail: choylw@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 16 July 2007; Accepted: 7 September 2007

Abstract

Objectives: To identify clinical determinants of length of psychiatric inpatient stay.

Participants and Methods: Seven hundred and sixty psychiatric inpatients were included. Socio-demographic, administrative, clinical, treatment, and service factors were retrieved from patients' records.

Results: The mean length of stay was 62 days. Ethnicity, marital status, occupation, priority follow-up status, type of discharge, criminal record, diagnosis, history of aggression and suicide attempts, duration and number of past psychiatric admissions, age of onset and duration of illness, use of medication, consultation needed, number of consultations needed, transfer needed, day hospital arrangement after discharge, occupational therapy, and medical social worker services were all found to correlate significantly with length of stay (p < 0.05). These variables accounted for 47.6% of the total variance in length of stay. Length of stay has no correlation with readmission within 1 and 3 months.

Conclusions: Since many predictive variables for the length of stay of patients are readily available on admission, early efforts should be made to identify potential long-stay patients and proactive measures should be implemented to minimise their length of stay.

Key words: Length of stay; Mentally ill patients; Socioeconomic factors

摘要

目的:探討影響精神科病人住院時間的臨床因素。

參與者與方法:研究對象為760位精神科病人。從病人紀錄中找出社會人口學、行政、臨床、治 療、及服務方面的因素。

結果:病人平均住院時間為62天。與住院時間相關的因素有:種族、婚姻狀況、職業、優先隨約、出院理由、犯罪紀錄、診斷、攻擊行為及自殺紀錄、過往因精神病入院的次數及時間、首發精神病的年齡會及病期、用藥紀錄、就診需要及次數、轉介、職業治療、醫務社會工作者的服務(p < 0.05) 。這些變項影響47.6%住院時間的變數。住院時間長短與1 至3個月內再入院無關。

結論:多項影響住院時間的因素,都可在入院時知悉。應及早辨認出有機會長住醫院的病人,並採取積極的措施,減少病人的住院時間。

關鍵詞:住院時間、精神科書病人、社會經濟學因素

Inpatient stays in psychiatric hospitals are longer than those seen in all other specialties. Since inpatient stay is usually the most expensive aspect of patient care,1 an understanding of the determinants of inpatient stay can help to better predict the length of stay (LOS). This may, in turn, improve budgeting and management of healthcare costs. Previous studies have demonstrated the role of a number of clinical determinants in the LOS in psychiatric hospitals. While some studies found that older patients are more prone to stay longer,2-8 one study found that those in the extreme age-groups (under 20 and over 60 years of age) were more susceptible.9 Numerous studies have found that unmarried patients,5,9-13 and those living alone1,14 or not living with family,10 have longer LOS. One study reported that male patients left hospital earlier than female patients.11 Migrant status was associated with shorter LOS in one German study15 while unemployment and lower educational level are associated with longer hospitalisation.5,9,11

Psychiatric diagnosis has been the most extensively studied variable that affects LOS. Schizophrenia, mood disorders, and learning disabilities predict longer LOS in many studies1,3,6,15-17 while adjustment disorders18,19 and personality disorders predict shorter LOS.6,18 Depression, dementia, and organic disorders predict longer LOS in psychogeriatric populations.9,20 Patients with co-morbid psychiatric diagnoses are discharged earlier than those with a single diagnosis.15 Some studies have found, however, that psychiatric diagnosis alone is not a good predictor of LOS.21,22 Substance and alcohol abuse was consistently associated with shorter LOS in many studies.3,4 A history of violence and self-harm was found to be an important predictor of a longer LOS.23 Some treatment factors have been investigated. Electro-convulsive therapy treatment during hospitalisation predicted a longer LOS.1,2,24 One study reported that clozapine treatment is associated with a decrease in hospital bed-days among patients with chronic schizophrenia.25 Patients with chronic medical illnesses tend to stay longer.10,26 The impact of a physical illness on LOS (usually making them tend to stay longer) is particularly strong in depressed patients.27,28 A multiplicity of previous psychiatric admissions is associated with an increased LOS in many studies2,3,14,29 but one showed that patients with fewer previous admissions stayed longer.5 Duration of the previous admission correlates positively with LOS12 and the number of inter-disciplinary consultations for non- psychiatric health problems during hospitalisation also correlate positively with LOS.2,24

Problems with aftercare and living arrangements accounted for a long LOS in some studies.30 Some patients lose their abode during the acute illness and finding suitable placements for them often takes a long time.31 Therefore, the availability of strong step-down programmes, day hospitals, and outreach programmes facilitate shorter LOS.32-34 Some clinical administrative indicators have been shown to correlate with LOS. For instance, ‘circumstance on admission’ (i.e. who accompanied the patients on admission) is a significant determinant of LOS. Patients not accompanied by anyone on admission stayed longer.14 Voluntary patients stay for shorter periods11 while patients admitted under compulsory orders stay longer.2 Some studies have shown that brief admissions lead to frequent readmissions35,36 but a recent systematic review asserted that a planned short-stay policy does not encourage a ‘revolving door’ pattern of admission for people with serious mental illness.37 Mattes38 also found that a longer LOS did not decrease subsequent readmissions, improve social adjustment, or decrease psychopathology. There is a paucity of data on the clinical determinants of LOS in Chinese populations.39 Being a housewife, an unemployed woman, single, in an older age-group, and having a history of violence are all associated with a longer LOS. Among the clinical reasons for detaining patients at hospital, ‘danger to others’ or ‘socially disruptive’ were quoted as barriers for discharge.40

Delivery of a comprehensive psychiatric service based in a general hospital has been the general trend in the mental health service in Hong Kong. The Department of Psychiatry of the Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital (PYNEH) is one such newly established regional psychiatric unit, serving Hong Kong Island and the Eastern Kowloon regions since the 1990s. This study aimed to examine the clinical determinants of the LOS of patients in this clinical setting and to investigate the relationship between LOS and readmission rate. The PYNEH Ethics Committee approved this study. Permission was also given by the Chief of Service of the psychiatric unit of PYNEH to review the psychiatric case records.

Methods

Subjects

The cases studied were patients who resided in the districts served by the Hong Kong East Cluster Hospitals (an official regional hospital network defined geographically by the Hospital Authority) and were admitted to the Psychiatric Inpatient Unit of PYNEH during the 1-year period from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2001. Cases were identified and retrieved through Hospital Authority computerised clinical records (also known as the Clinical Management System [CMS]).

If a patient was admitted to the PYNEH Psychiatric Inpatient Unit more than once during the study period, information would be obtained from the first admission only. Patients not residing in districts served by the Hong Kong East Cluster Hospitals before the index admission were excluded. Patients admitted during the study period but not yet discharged by 31 December 2004 were also excluded.

Measurement

The information abstracted from case notes included the admission records, treatment progress, and case summary. Information was also gathered from the CMS to retrieve different potential variables for predicting LOS.

Socio-demographic Factors

These included age on index admission, gender, race, language, marital status, education, occupation, living situation before admission (i.e. whether the patients lived alone or with relatives or friends), living condition before admission (e.g. own home or hostel), circumstances on admission (i.e. whether the patient was accompanied by relatives or friends upon admission to ward), discharge destination (e.g. returning home / admission to half- way houses [HWH] / old-age homes [OAH] / other institutions).

Administrative Factors

These included sources of referral (i.e. different hospitals and clinical departments), legal status upon admission (i.e. compulsory or voluntary admission), priority follow-up (PFU) status (i.e. a system used in Hong Kong to classify patients according to their violent propensity: non-PFU for absence of history of significant violence, target and sub- target for cases with violent propensity), criminal record, type of discharge (i.e. whether they were discharged against medical advice, with improvement or in remission, died or absconded, etc.), and legal status upon discharge.

Clinical Factors

These included clinical diagnoses according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision criteria (World Health Organization, 1992), co-morbidity, family history of mental illness, number of previous psychiatric admissions (including admission to other hospitals), age of onset of psychiatric illness, duration of illness from the onset, duration of last psychiatric admission, number of chronic medical illnesses (those requiring regular follow- up and treatment), previous aggression, aggression before admission, victims of aggression (i.e. relatives or hospital staff or others), history of suicide, suicide attempt before admission, substance misuse (past or current use; regular or recreational use; types of illicit drugs used), alcohol misuse (i.e. excessive use / alcohol dependence / chronic use with complications).

Treatment Factors

These included electroconvulsive therapy during hospitali- sation, psychotropic medication including depot medica- tion, atypical antipsychotics, clozapine, services provided by clinical psychologists, medical social workers (MSWs), occupational therapists (OT), community psychiatric nurses, physiotherapists, interdisciplinary consultations for non-psychiatric problems during the index admission (i.e. consultations with other departments of PYNEH for care of medical problems), number of consultations needed, transfer needed (i.e. transfer to other specialty wards of PYNEH).

Service Factors

We also examined whether patients had received any special rehabilitation programmes. There are 3 main psychiatric rehabilitation services provided: Rehabilitation Oasis (R.O.), EXITERS programme, and day hospital. Rehabilitation Oasis is mainly a rehabilitation programme for patients on waiting lists for HWH. The EXITERS programme was started in July 2002 at PYNEH. Its main focus is to provide intensive rehabilitation in a home-like setting for patients that have been hospitalised for more than 6 months, in order to help them to integrate into the community again. The day hospital provides an after-care rehabilitation programme for discharged patients who need regular, close supervision.

Length of Stay and Readmission

The number of days a patient stayed in hospital during the index admission, including the day of discharge and days during home leave trials away from wards, was recorded. Data on readmissions within 1 and 3 months were collected.

Statistical Analysis

Prior to the performance of a multivariate analysis of the clinical determinants of LOS, univariate analyses were used to compare LOS across different categorical groups using an independent sample t test for a 2-sample comparison and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for a multi- group comparison. When using the ANOVA, a post-hoc Scheffe’s multiple-range test was used to minimise type-I errors resulting from multiple comparisons. For continuous independent variables (e.g. age), either Pearson or Spearman rank correlation analyses were performed, depending on the parametric properties of the variables in question. A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed to examine the major determinants of LOS and a stepwise multiple regression analysis was also done to explore any independent variables that should be included in the model. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 level. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Windows version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, US).

Results

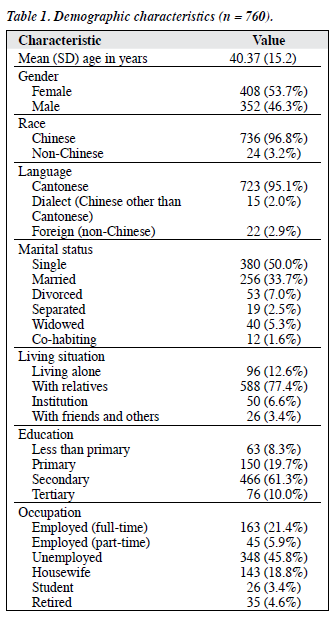

A total of 797 admissions met the inclusion criteria during the study period, 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2001. Of these 797 patients, 4 (0.5%) were still inpatients by 31 December 2004, so were excluded. Of the remaining 793 patients, case records and data were available for 760 (over 95%). These 760 cases became the subjects of this study. The mean LOS was 62.4 days and the median was 30.0 days; 13.3% of the cases were discharged within 1 week, 85.3% of them were discharged within 3 months, and 93.2% within 6 months.

Sample Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of cases are shown in Table 1. A total of 577 (75.9%) subjects were admitted as voluntary patients while 177 (23.3%) were compulsorily admitted, 6 (0.8%) were informal cases. Regarding PFU status, 684 (90.0%) patients belonged to the non-PFU group, 68 (8.9%) were target cases, and 7 (0.9%) were sub- target cases. A total of 673 (88.6%) cases had no previous criminal records. Sixty (7.9%) subjects were discharged against medical advice.

The most common principal psychiatric diagnoses were schizophrenia and psychotic disorders (n = 426, 56.1%). This was followed by depressive disorders (n = 106, 13.9%), bipolar affective disorders (n = 76, 10.0%), substance- and alcohol-related disorders (n = 55, 7.2%), adjustment disorders (n = 33, 4.3%), and dementia and organic disorders (n = 19, 2.5%). Co-morbidity was present in 131 (17.2%) subjects. One hundred and ninety six (25.8%) patients had chronic medical illnesses; 168 (22.1%) had a family history of mental illness; 191 (25.1%) had a history of suicide attempts and 77 attempted suicide before the index admission. One hundred and thirty one (17.2%) patients had a history of aggressive behaviour and 72 displayed aggression before the index admission. Alcohol- related problems were present in 41 (5.4%) subjects; 106 (13.9%) had a history of illicit drug use and 76 were regular users. Five subjects received electroconvulsive therapy during the index admission; 202 (26.6%) received depot medication and 20 (2.6%) received clozapine. Two hundred and sixteen (28.4%) subjects received occupational therapy, 310 (40.8%) got assistance from the MSW, 75 (9.9%) received clinical psychology sessions, and 196 (25.8%) were attended by a community psychiatric nurse. One hundred and fifty four (20.3%) subjects needed consultation with other departments during hospitalisation and 21 needed transfer to other specialty wards. Forty two (5.5%) patients received services from our rehabilitation team; 3 of these joined R.O., 4 joined the EXITERS programme, and 35 joined the day hospital upon discharge.

Factors Affecting Length of Stay

Those patients who were Chinese, single, and unemployed stayed longer than married patients. Patients discharged to HWH and OAH stayed much longer than patients discharged home. Those with a PFU-target status stayed longer than non-PFU cases and patients with criminal records also stayed longer. Diagnostic groups correlated with LOS. The LOS in subjects with schizophrenia and psychotic disorders was significantly longer than that of patients with depressive disorders. Patients with a previous history of aggression stayed longer. The duration of the last psychiatric admission, number of previous psychiatric admissions, age of onset, and duration of illness were all found to have a significant correlation with LOS. There were 426 (56.1%) subjects in the sample with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and psychotic disorder. Significant factors affecting LOS in this subgroup are shown in Table 2.

Predictors of Length of Stay

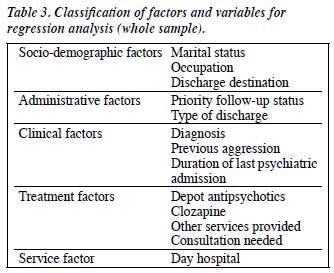

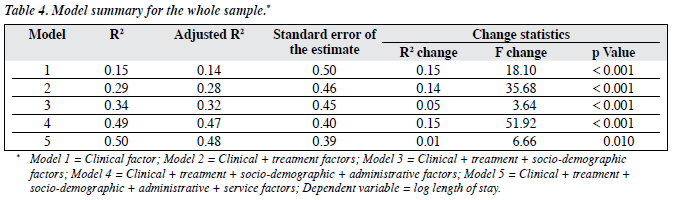

Of the variables correlating significantly with the LOS, those variables that were subsets or duplicates of other variables were excluded from the final analysis. The variables included in the final regression model are shown in Table 3 and the model summary is displayed in Table 4. The variables in the final model explained 47.6% (adjusted R2 = 0.476) of LOS of the whole sample.

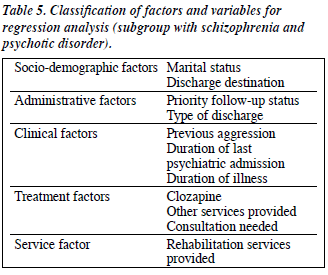

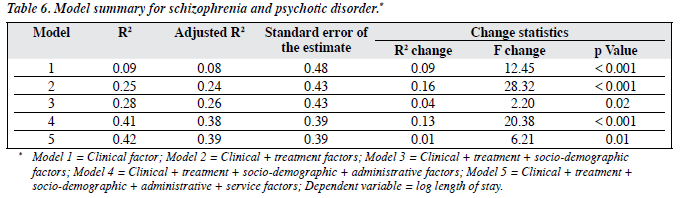

For the schizophrenia and psychotic disorders subgroup, the selected variables are listed in Table 5 and the model summary is shown in Table 6. The sequence of factors entered in the model was: first the clinical factors, followed by treatment factors, then the socio-demographic factors, administrative factors and, finally, the service factors. The 11 variables in the final model explained 38.9% (adjusted R2) of the total variance in LOS.

Length of Stay and Readmission

Fifty one patients were readmitted to hospital within 1 month and 91 were readmitted within 3 months. It was found that LOS had no statistically significant correlation with readmission within 1 and 3 months (p = 0.64 for 1 month, p = 0.89 for 3 months).

Discussion

In this study, the case notes for 95% of all eligible patients were retrieved. The case notes, along with supplementary information from the CMS, were judged to be sufficient to address the key objectives of this study. This study may be limited by being conducted at the Department of Psychiatry in PYNEH. Our results may not be generalisable to other psychiatric service settings in Hong Kong due to intrinsic differences in hospital administration, service infrastructure, and the socio-economic status of different catchment populations. For instance, in our study the mean LOS is 62 days and median is 30 days. Also, 85.3% of the cases in this study sample were discharged within 3 months, compared with only 55% in a survey done at Castle Peak Hospital (CPH).40 Most (93.2%) of our patients were discharged within 6 months and 96.8% within 12 months compared with 85% within 12 months at CPH.40 Despite these intrinsic limitations, the sampling frame chosen was considered appropriate. Firstly, patients living in districts served by other hospital clusters will receive outpatient follow-up care in other settings. Our sampling method minimised the administrative and service factors that can confound LOS and readmission. Secondly, an examination of more recent samples would not allow adequate observation of the LOS and would thus compromise an examination of the determinants of LOS. Other than the readmission rate, other outcome variables, such as carers’ burden, suicide rates during post- discharge period and violence, that might affect LOS, were not examined. As in all retrospective care records review studies, the quality of case note documentation affects the result. Moreover, some important potential determinants of LOS, e.g. the severity of the psychiatric illness, symptom profiles, level of functioning etc. cannot be retrieved from case records.

Chinese patients stayed longer than non-Chinese patients. Such a finding is consistent with western studies.15,19

As many of the non-Chinese patients were domestic helpers from South-east Asia, most returned to their home countries with their employment contracts terminated after they were admitted to the psychiatric unit. There was a tendency for single patients to stay longer.10-13 While the observation of longer LOS in unemployed patients replicated that seen in other studies,5,11 occupational status was not significantly associated with LOS in the schizophrenia subgroup. It is postulated that many of those patients with schizophrenia who were described as having ‘employment’ actually worked in sheltered workshops or under a supported employment scheme. Patients discharged to HWH and OAH stayed in hospital much longer than those returning home. This reflected the long waiting times for HWH and OAH places.40

Subjects with a history of aggression stayed longer, a finding consistent with a past study.23 Patients with a history of suicide attempts before admission stayed for shorter periods.18 It was also shown that ‘danger to self’ was less frequently quoted as a reason for detaining a patient in hospital than ‘danger to others’.40 This reflected that psychiatrists tended to let patients with aggressive histories stay for longer, but not the suicidal ones. The reasons might be 2-fold: first, depressive symptoms may be more responsive to treatment; and second, and more importantly, attempted suicide is not regarded as serious as the killing or wounding of others.

In this study, it was observed that patients receiving depot antipsychotics stayed longer. This may be attributed to the typical clinical profile of depot recipients who usually have limited insight and poor drug compliance and require longer hospitalisation for stabilisation. Patients on clozapine treatment tended to stay longer, contrary to the study by Reid et al,25 who found that clozapine was associated with a decrease in hospital bed-days for patients with chronic schizophrenia. In our local clinical context, clozapine treatments are usually started during the index admission for resistant symptoms of schizophrenia and such clinical decisions are usually made after a reasonable period of inpatient treatment. Moreover, the need for 18 consecutive weekly white cell counts for drug safety monitoring adds a longer stay. The LOS might be lower in this group if we follow them up for an adequate period of time. In a local study of problems associated with discharge, among the procedural reasons for delay in discharge, ‘OT or MSW assessment not ready’ was the most frequently cited reason.40 The other reason might be that long-stay patients are more likely to be referred to the MSW for placement problems, which in turn warrants referral to the OT to prepare them for community living in residential rehabilitation facilities. Patients who were discharged with day hospital support spent a much shorter time in hospital. The availability of outpatient alternatives like day treatment encourages rapid discharge.

In the final regression model of the full sample, the 13 variables were able to explain 47.6% of the total variance in LOS. This was much higher than in western studies.14,32 The present study design could be improved by adding a validation sample to test the regression model and the predictive factors. For instance, a multi-centre study would be a useful means of investigating the effect of institutional factors such as admission criteria and treatment philosophy on LOS. Assessment of symptomatology and global functioning, using a dimensional approach, will add useful information for predicting LOS on top of the categorical diagnosis; this can be achieved with a prospective study. As many of the factors significantly associated with discharge were readily available on admission, efforts to identify potential long-stay patients should be made early and proactive measures should be implemented to minimise the LOS.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Miss Crystal Chow, PYNEH statistician for generating the patient list and all the staff of our medical records office for helping locate the case records.

References

- Creed F, Tomenson B, Anthony P, Tramner M. Predicting length of stay in psychiatry. Psychol Med 1997;27:961-6.

- Blais MA, Matthews J, Lipkis-Orlando R, Lechner E, Jacobo M, Lincoln R, et al. Predicting length of stay on an acute care medical psychiatric inpatient service. Adm Policy Ment Health 2003;31:15- 29.

- Huntley DA, Chow DW, Christman J, Csernansky JG. Predicting length of stay in an acute psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Serv 1998;49:1049- 53.

- Jayaram G, Tien AY, Sullivan P, Gwon H. Elements of a successful short-stay inpatient psychiatric service. Psychiatr Serv 1996;47:407- 12.

- Munley PH, Devone N, Einhorn CM, Gash IA, Hyer L, Kuhn KC. Demographic and clinical characteristics as predictors of length of hospitalization and readmission. J Clin Psychol 1977;33:1093-9.

- McLay RN, Daylo A, Hammer PS. Predictors of length of stay in a psychiatric ward serving active duty military and civilian patients. Mil Med 2005;170:219-22.

- Stoskopf C, Horn SD. Predicting length of stay for patients with psychoses. Health Serv Res 1992;26:743-66.

- Sajatovic M, Donenwirth K, Sultana D, Buckley P. Admissions, length of stay, and medication use among women in an acute care state psychiatric facility. Psychiatr Serv 2000;51:1278-81.

- Rud J, Noreik K. Who become long-stay patients in a psychiatric hospital? Acta Psychiatr Scand 1982;65:1-14.

- Allodi F, Cohen M. Physical illness and length of psychiatric hospitalization. Can Psychiatr Assoc J 1978;23:101-6.

- 1 Altman H, Angle HV, Brown ML, Sletten IW. Prediction of length of hospital stay. Compr Psychiatry 1972;13:471-80.

- Jakubaschk J, Waldvogel D, Wurmle O. Differences between long-stay and short-stay inpatients and estimation of length of stay. A prospective study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1993;28:84-90.

- Laessle RG, Yassouridis A, Pfister H. Sociodemographic characteristics and length of psychiatric hospital stay: application of a proportional hazards model. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1988;77:349-51.

- Cyr JJ, Haley GA. Use of demographic and clinical characteristics in predicting length of psychiatric hospital stay: a final evaluation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983;51:637-40.

- Stevens A, Hammer K, Buchkremer G. A statistical model for length of psychiatric in-patient treatment and an analysis of contributing factors. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001;103:203-11.

- Hallak JE, Crippa JA, Vansan G, Zuardi AW. Diagnostic profile of inpatients as a determinant of length of stay in a general hospital psychiatric unit. Braz J Med Biol Res 2003;36:1233-40.

- Saeed H, Ouellette-Kuntz H, Stuart H, Burge P. Length of stay for psychiatric inpatient services: a comparison of admissions of people with and without development disabilities. J Behav Health Serv Res 2003;30:406-17.

- Brock IP 3rd, Brown GR. Psychiatric length of stay determinants in a military medical center. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1993;15:392-8.

- Tucker P, Brems C. Variables affecting length of psychiatric inpatient treatment. J Ment Health Adm 1993;20:58-65.

- Draper B, Luscombe G. Quantification of factors contributing to length of stay in an acute psychogeriatric ward. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1998;13:1-7.

- Caton CL, Gralnick A. A review of issues surrounding length of psychiatric hospitalization. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1987;38:858- 63.

- McCrone P, Phelan M. Diagnosis and length of psychiatric in-patient stay. Psychol Med 1994;24:1025-30.

- Greenfield TK, McNiel DE, Binder RL. Violent behavior and length of psychiatric hospitalization. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1989;40:809- 14.

- Herr BE, Abraham HD, Anderson W. Length of stay in a general hospital psychiatric unit. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1991;13:68-70.

- Reid WH, Mason M, Toprac M. Savings in hospital bed-days related to treatment with clozapine. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1994;45:261- 4.

- Lyons JS, McGovern MP. Use of mental health services by dually diagnosed patients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1989;40:1067-9.

- Schubert DS, Yokley J, Sloan D, Gottesman H. Impact of the interaction of depression and physical illness on a psychiatric unit’s length of stay. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1995;17:326-34.

- Sloan DM, Yokley J, Gottesman H, Schubert DS. A five-year study on the interactive effects of depression and physical illness on psychiatric unit length of stay. Psychosom Med 1999;61:21-5.

- Hopko DR, Lachar D, Bailley SE, Varner RV. Assessing predictive factors for extended hospitalization at acute psychiatric admission. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:1367-73.

- Levine MS, Weiner OD, Carone PF. Monitoring inpatient length of stay in a community mental health center. J Nerv Ment Dis 1978;166:655- 60.

- Kirshner LA, Johnston L. Length of stay on a short-term unit. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1985;7:149-55.

- Okin RL, Pearsall D, Athearn T. Predictors about new long-stay patients: were they valid? Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:1596-601.

- De Francisco D, Anderson D, Pantano R, Kline F. The relationship between length of stay and rapid-readmission rates. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1980;31:196-7.

- Thompson EE, Neighbors HW, Munday C, Trierweiler S. Length of stay, referral to aftercare, and rehospitalization among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv 2003;54:1271-6.

- Kennedy P, Hird F. Description and evaluation of a short-stay admission ward. Br J Psychiatry 1980;136:205-15.

- Appleby L, Desai PN, Luchins DJ, Gibbons RD, Hedeker DR. Length of stay and recidivism in schizophrenia: a study of public psychiatric hospital patients. Am J Psychiatry 1993;150:72-6.

- Johnstone P, Zolese G. Length of hospitalization for people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD000384.

- Mattes JA. The optimal length of hospitalization for psychiatric patients: a review of the literature. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1982;33:824-8.

- Fan BY, Siegel C, Goodman AB, Lin SP, Yeh EK. Length of hospital stay for active treatment psychiatric patients in Taiwan. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei) 1987;40:245-54.

- Cheung HK. Survey of discharge problems in Castle Peak Hospital. Memo of Castle Peak Hospital; August 1984.