Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2009;19:97-102

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

中文版的執行功能測試(C-EXIT25)在香港華籍人口中的最 佳切點分數

陳秀雯、李曉媚、彭麗君、黃秀雯、趙鳳琴、林翠華

Prof Sandra Sau-man Chan, MRCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), FHKCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Ms Catherine Hiu-mei Li, BSocSc (Hons), MSW, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Ms Shirley Lai-kwan Pang, Hons Dip (Coun & Psy), BSc (Hons), Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Ms Corine Sau-man Wong, BCogSc (Hons), Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Prof Helen Fung-kum Chiu, FRCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), FHKCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Prof Linda Chiu-wa Lam, FRCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), FHKCPsych, MD, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Prof Sandra SM Chan, Department of Psychiatry, G/F, Multicentre, Tai Po Hospital, 9 Chuen On Road, Tai Po, Hong Kong, China.

Tel: (852) 2607 6025; Fax: (852) 2667 1255;

E-mail: schan@cuhk.edu.hk

Submitted: 14 November 2008; Accepted: 5 January 2009

Abstract

Objectives: To determine the optimal cut-off score on the Chinese version of the Executive Interview to discriminate all-cause dementia patients from non-dementia subjects.

Participants and Methods: A total of 141 community-dwelling elders were assessed with the Chinese version of the Executive Interview, the Cantonese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination, and Nelson’s Modified Card Sorting Test. Severity of dementia was determined using the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale.

Results: Higher total scores on the Chinese version of Executive Interview (greater impairment) yielded a statistically significant negative correlation with Nelson’s Modified Card Sorting Test’s ‘Number of categories’, but positive correlations with the test’s ‘Errors’, ‘Perseverative errors’, ‘Non-perseverative errors’, and ‘Percentage of perseverative errors’. The sensitivity and specificity at different cut-off values on the Chinese version of the Executive Interview used to plot the receiver operating characteristic curve gave an area under the curve of 0.97 (95% confidence interval, 0.94-0.99; p ≤ 0.01). The cut-off value of 15 best distinguished Clinical Dementia Rating 0 and 0.5 from Clinical Dementia Rating 1 and 2 (sensitivity = 90.7%; specificity = 87.2%).

Conclusions: The results of the current study and the previous pilot study support that the Chinese version of the Executive Interview as a potentially useful bedside tool for executive functional assessment in Chinese elders, by virtue of good internal consistency, inter-rater reliability, concurrent validity and discriminatory power.

Key words: Aged; Dementia; Geriatric assessment; Neuropsychological tests; Psychiatric status rating scales

摘要

目的:探討香港華籍人口中,使用中文版的執行功能測試分辨痴呆症患者及非痴呆症患者的最 佳切點分數。

參與者與方法:共141位居住在社區的老人接受中文版的執行功能測試、廣東話版的簡短智能測 驗,及Nelson的修改式卡片分類測驗。並使用臨床痴呆評估量表量度痴呆症的嚴重程度。

結果:中文版的執行功能測試得分高,與Nelson的修改式卡片分類測驗中的「分類數」呈顯著 負相關,但與「錯誤」、「持續性錯誤」、「非持續性錯誤」,以及「持續性錯誤的百分比」 呈顯著正相關。中文版的執行功能測試在不同切點的敏感性及特異性在ROC曲線下之區域為 0.97(95%置信區間:0.94-0.99;p £ 0.01)。切點為15最能分辨臨床痴呆評估量表0-0.5及1- 2(敏感性 = 90.7%;特異性 = 87.2%)。

結論:根據內部一致性、評分者信度、同時效度、以及辨別力,本研究及過往一項先導研究的 結果均顯示,中文版的執行功能測試是用於檢測華籍老年人執行功能一種有用的臨床工具。

關鍵詞:年老、痴呆症、老人檢測、醫科學生、神經心理測試、精神狀態量表

Introduction

‘Executive control functions’ (ECFs) broadly encompass a range of cognitive skills that are responsible for the planning, initiating, sequencing, and monitoring of complex goal-directed behaviour. Well-known executive tests like the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), the Stroop, the Category Test, and Trails B have been specifically associated with frontal lobe structural or metabolic changes.1-5 Classical ECF measures are often multidimensional and no single measure comprehensively assesses all ECF domains. The ECF has not been a routine domain for clinical assessment, by virtue of its perceived complex construct by most clinicians. The relative paucity of validated bedside instruments is another reason. Although these ECF measures have a reasonably high level of validity,6 they are not user- friendly as bedside clinical tools. Consequently, they are often restricted to research endeavours, and their use for daily clinical assessment of ECF is limited.7-9

It is generally agreed that an ideal bedside instrument should be user-friendly for most frontline carers (including non-professionals), feasible (not time-consuming or demanding for auxiliary tools), and reliable across situations and between raters. For the purpose of screening, it should also have reasonable validity, which includes good sensitivity and specificity. One of the examples is the Folstein’s Mini-Mental State Examination available since 1970s, which is a short bedside tool that has become a popular test for screening out patients with dementia and monitoring disease progress. In terms of ECF assessment, a validated bedside measure of executive dyscontrol known as the Executive Interview (EXIT25) contains 25 items and requires 15 minutes to administer.10 It is a structured interview and the comprehensive range of symptoms of executive failure elicited by it include: perseveration, imitation behaviour, echopraxia, echolalia, intrusions, frontal release signs, lack of spontaneity, prompting, disinhibited and utilisation behaviours. It was reported to have high internal consistency (a = 0.85) and inter-rater reliability (r = 0.91). Scores of the EXIT25 also correlate well with WCST categories (r = 0.54), Trail Making Part B (r = 0.64), the Test of Sustained Attention (Time, r = 0.82; Errors, r = 0.83), and Lezak’s Tinker Toy Test (r = 0.57). Scores range from 0 to 50 with high scores indicating impairment. A score of 15/50 best discriminates normal elderly from all-cause dementia (sensitivity = 0.93, specificity = 0.83, area under the receiver operating characteristic [ROC] curve [AUC] = 0.93, n = 200).

There is dearth of data concerning ECF profiling in Chinese elders. Since performance in standardised ECF tests are often subject to educational level and cultural biases,11,12 validation of a user-friendly bedside instrument in the Chinese language may provide an alternative convenient tool for such profiling in our locality, which is suitable for daily clinical practice. We have previously reported the results of a pilot study on the correlational properties of the Chinese version of Executive Interview (C-EXIT25) with formal ECF measurement and other validated global cognitive tests for elders.13 That study showed that C- EXIT25 has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s a = 0.79) and inter-rater reliability (r = 0.91, p < 0.01). The correlational properties of the C-EXIT25 to provide indices of the Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (MCST)8,14,15 were superior to the Cantonese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (C-MMSE)16 and the Chinese version of the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale,17 even after adjusting for age, gender, and educational level. It also discriminates different stages in Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR).18,19 Given the small sample size and the inadequate number of normal controls in the pilot study, we lacked the statistical power to set up a ROC analysis to examine how well the C-EXIT25 discriminates normal from dementia subjects at different cut-off points. The objective of this study was to determine the optimal cut-off score on the C-EXIT25 that discriminates all-cause dementia from non-dementia subjects.

Methods

The details of translation, back-translation, pilot-application and adaptation were reported in another paper.13 In brief, the original English version of EXIT2510 was translated to Chinese and back-translated to affirm its face validity. Items on ‘Number-Letter Task’, ‘Word Fluency Task’, ‘Anomalous Sentence Repetition’, ‘Memory/Distraction Task’, ‘Interference Task’, and ‘Serial Order Reversal Task’ required major adaptation to fit into our local cultural / linguistic context. This was because direct translation was not appropriate for the following reasons: (1) The basic linguistic unit in the English language is the alphabet, while ideographic characters are used in Chinese, there being no grammatically equivalent expressions in Chinese. (2) The translated items were not common colloquial expressions and demanded a sophisticated level of comprehension. (3) The task becomes too easy even for highly impaired subjects, after direct translation. For example, in the “Number-Letter Task” (Item 1), the alphabets A to E are changed to the non- numerical chronological words of “甲,乙,丙,丁,戊” since none of the study participants understand English, and these chronological words are well-known to most local Chinese without reliance on a sophisticated education. In the “Memory/Distraction Task” (Item 6), the 3 items used are “Apple”, “Train”, “Newspaper” in Chinese language, as in the 3-item registration and retrieval test in C-MMSE.16 These 3 items have the same number of syllables in Chinese and are common daily commodities from different categories. The original EXIT25 uses forward and backward spelling of the word “Cat” after the initial registration, so as to distract subjects before retrieval of the 3 registered items. Again, due to different language structure, we added questions about the appearance of a cat such as “how many legs does a cat have?” or “how many ears?” or “how many tails” to serve as a distraction, and we trust that the level of difficulty relative to our local elders was compatible with that in the original version targeted at English-speaking elders. Such semantic contexts also introduce the same interference with the subsequent retrieval of registered items, so that some impaired participants add words related to “Cats” during subsequent recall. As for the “Interference Task” (Item 7), the original version uses “Brown” printed in black while we use “Red” (in Chinese) printed in black. It is adapted this way, since the Chinese expression for the English word “Brown” has 2 Chinese characters, and to local elders of elementary educational level, such characters are not as well-known as the word “Red” expressed in a single Chinese character. Lastly, the “Serial Order Reversal Task” (Item 22) was totally revamped since the original English version asked subjects to recite months of the years backward, while most of the calendar nomenclatures in the Chinese language are simple numerical values, making the task too simple for most impaired elders. Although there are some forms of calendar nomenclature that use distinct non-numerical chronological phrases or words, they are too difficult for even highly educated local elders and hence were considered not applicable. Taking into account all these linguistic and cultural limitations as well as the tentative construct of this task (testing serial order reversal on well-learnt sequences that demand moderately sustained attention), we asked subjects to do serial-2 subtractions starting from 20. The serial-2 subtraction (a common bedside test) taxes executive function since it requires reorganising a well-learnt set with good working memory and sustained attention, which cannot be completed solely by relying on semantic retrieval of memory. The length of this task is similar to the “Calender” version of the original EXIT25, and being reasonably free of educational bias — it does not demand sophisticated scholastic skills.

The initial translated Chinese version was administered to 15 consenting elders conveniently recruited from a psychogeriatric outpatient clinic for a pilot run. Minor final modifications were made to the questionnaire before administering it formally to our recruits.

Subjects and Assessments

Elders, aged 65 years or above, and capable of giving written informed consent (or with available next-of-kin to give consent in case of mental incapacity), were conveniently selected from several psychogeriatric clinics. The latter included clinics of The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) and several local community elderly facilities. Recruitment was in 2 periods (2003-2004 and 2005-2007). The subjects were selected irrespective of their diagnoses or co-morbid medical conditions. Dementia staging, defined by CDR18,19 was assigned by an independent psychiatrist blinded to the C-EXIT25 scores. The assessment battery (detailed below) was administered by 2 research assistants who received relevant training in the pilot phase of the study, during which they achieved satisfactory inter-rater reliability (Pearson correlation, 0.91; p < 0.01). Exclusion criteria were: stage 3 (severe) dementia on CDR, inability to follow simple commands, inability to speak Cantonese, or sensory / physical deficits that precluded performing the testing procedures.

Details of the assessment entailed the following:

- Demographics (gender, age, educational level, marital status, living arrangements, and physical health screen), which were all charted on a standard data entry form.

- The C-EXIT25 described

- The C-MMSE,16 which is an 11-item brief bedside cognitive test that comprises questions on time / place orientation, memory (immediate and delayed recall), ideomotor praxia, language and visuo-spatial tasks. It has been validated in Chinese and has been widely used in daily clinical practice and

- The MCST,8,14,15 which utilises 2 identical subsets of 24 response cards out of the 128 original cards used in the WCST, given out in a particular sequence, such that no consecutive cards share the same attribute (form, colour, and number). The test also allows subjects to decide the initial sequence of sorting principles in the first 3 categories. The number of consecutive correct sorts is reduced from 10 to 6 for a category to be The test is halted when the 3 categories are completed twice or when all 48 response cards have been exhausted. The MCST has proved popular with researchers investigating ECF and is able to discriminate between patients with frontal lobe lesions and normal controls, but is rather equivocal for differentiating subjects with the former and those with non-frontal lobe lesions.20 Despite its shortcomings compared to the full WCST (lack of detailed psychometric profiling, and normative), it was nevertheless chosen for this study, because in our prior experience the full WCST was too cumbersome for our local elderly with a limited level of education. Moreover, the MCST has been experimented with local community-dwelling Chinese people, whose performance profile correlated well with relevant demographic factors.14 It is thus a feasible alternative to the full version of the WCST and has local reference data.

This study protocol was approved by the Joint CUHK- New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CRE-2003.260; CRE-2004.103).

Data Analyses

The ROC curve was plotted using measures of sensitivity and specificity at various C-EXIT25 cut-off values. The ROC curve is used to demonstrate the overall discriminatory power of assessment tools over a range of cut-off values. The optimal cut-off value is indicated by the part of the curve closest to the upper left corner. The AUC is a measure of the diagnostic power of the test. A perfect test will have an AUC of 1.0, and AUC of 0.5 means the test performs no better than chance. All statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows version 16.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US).

Results

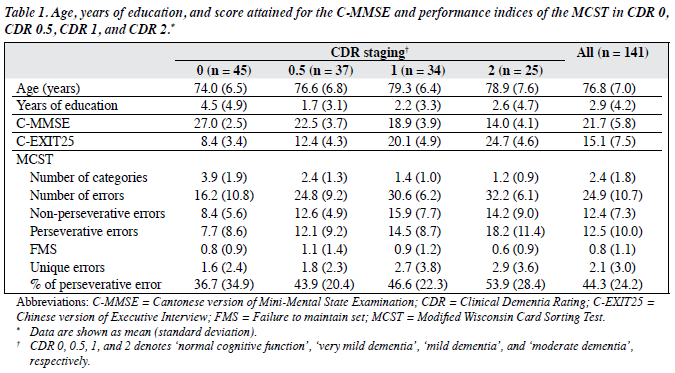

A total of 141 elders consented to participate in this study and completed all the assessments. There was a predominance of female subjects across all groups of dementia staging (female, 103; male, 38). The mean age of all the subjects was 76.8 (standard deviation, 7.0) years. The mean age and years of education of subgroups classified by the CDR staging are shown in Table 1. The CDR of 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 denotes ‘normal cognitive function’, ‘very mild dementia’, ‘mild dementia’, and ‘moderate dementia’, respectively.

Descriptive Profiles of the Cognitive Measures (Chinese Version of Executive Interview, Cantonese Version of Mini-Mental State Examination, Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test)

The mean total scores of the C-EXIT25 and C-MMSE as well as performance indices of the MCST (‘Number of categories’, ‘Total number of errors’, ‘Non-perseverative errors’, ‘Perseverative errors’, ‘Percentage of perseverative errors’, ‘Failure to maintain set’, ‘Unique errors’) across CDR stages 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 are shown in Table 1.

Correlations between Parameters of the Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and the Chinese Version of Executive Interview

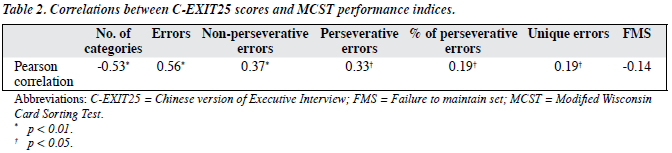

Table 2 shows that higher total scores on the C-EXIT25 (greater impairment) correlates negatively with ‘Number of categories’ but positively with ‘Errors’, ‘Perseverative errors’, ‘Non-perseverative errors’, and ‘Percentage of perseverative errors’ at statistically significant levels. The observed negative correlation between total score on the C- EXIT25 and ‘Failure to maintain set’ did not reach statistical significance.

Optimal Cut-off Score on the Chinese Version of Executive Interview that Distinguishes Subjects with Clinical Dementia Rating of 1 or Above from Others

Table 3 shows the sensitivity and specificity at different cut-off values on the C-EXIT25. Its AUC was 0.97 (95% confidence interval, 0.94-0.99; p ≤ 0.01). The cut-off value of 15 best distinguishes CDR 0 and 0.5 from CDR 1 and 2 (sensitivity = 90.7%; specificity = 87.2%).

Discussion

The results of the present study support the discriminant validity of the C-EXIT25 in Chinese elders, given that the AUC was close to 1.0 in the ROC analysis. A score of 15/50 on the C-EXIT25 best discriminates CDR 0 / 0.5 from CDR 1 / 2 cases with optimal specificity plus sensitivity. The concurrent validity for the C-EXIT25 has been discussed in a previous pilot study that compared the scores it yielded with those from the MCST (an alternative measure of ECF).13 In our pilot study,13 it was shown that the total C-EXIT25 score correlates moderately well at statistically significant levels with ‘Number of categories’ (Pearson correlation = –0.53, p < 0.01) and other performance indices of the MCST. Such observations are consistent with the original validation study of the EXIT25 in a Caucasian population, in which the Pearson correlation coefficient between the total score and the WCST category was -0.54.10

Our results need to be interpreted in the context of methodological limitations, which mainly arise from sampling. For instance, subjects were conveniently sampled from a community setting. Hence, we could not be sure of their representativeness with respect to the clinical population and community. However, the correlational properties of the C-EXIT25 to MCST performance indices in samples collected at 2 different time-points (the current study vs the pilot validation study13) retained a similar pattern, i.e. higher scores on the C-EXIT25 correlated negatively with the MCST category to a moderate degree (Pearson correlation coefficient approximated to -0.5, p < 0.01). This suggests the concurrent validity of the C-EXIT25 in elders was consistent in different samples that were not randomly selected from the reference population. The non-restrictive subject inclusion criteria adopted in this study (i.e. inclusion irrespective of diagnoses, co-morbid medical conditions or dementia subtype) allowed our results to be generalised to real- life clinical settings. Yet they also introduced unmeasured confounders that might have influenced subject performance in the respective cognitive tests. Future studies should be conducted in larger samples to examine the discriminant property of the C-EXIT25 in subtypes of dementia or subgroups classified by their different medical / psychiatric co-morbidities.

Conclusion

The results of the current study and the previous pilot study support that the C-EXIT25 is a potentially useful bedside tool for ECF assessment in Chinese elders, by virtue of good internal consistency, inter-rater reliability, concurrent validity, and discriminatory power.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Prof DR Royall for his kind permission to adapt the original EXIT-25 to Chinese and all his generous advice and support.

Declaration of interest

This study is supported by the US National Institute of Health’s Global Health Research Initiative Program For New Foreign Investigators (Grant Number: 5-R01TW0007256- 03).

References

- Milner B. Effects of different brain lesions on card sorting. Arch Neurol 1963;9:90-100.

- Drewe The effect of type and area of brain lesion on Wisconsin card sorting test performance. Cortex 1974;10:159-70.

- Malloy P, Rasmussen S, Braden W, Haier RJ. Topographic evoked potential mapping in obsessive-compulsive disorder: evidence of frontal lobe dysfunction. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:63-71.

- Marenco S, Coppola R, Daniel DG, Zigun JR, Weinberger Regional cerebral blood flow during Wisconsin Card Sorting Test in normal subjects studied by xenon-133 dynamic SPECT: comparison of absolute values, percent distribution values, and covariance analysis. Psychiatry Res 1993;50:177-92.

- Bench CJ, Frith CD, Grasby PM, Friston KJ, Paulesu E, Frackowiak RS, et al. Investigations of the functional anatomy of attention using the Stroop test. Neuropsychologia 1993;31:907-22.

- Royall DR, Lauterbach EC, Cummings JL, Reeve A, Rummans TA, Kaufer DI, et Executive control function: a review of its promise and challenges for clinical research. A report from the Committee on Research of the American Neuropsychiatric Association. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2002;14:377-405.

- Haaland KY, Vranes LF, Goodwin JS, Garry PJ. Wisconsin Card Sort Test performance in a healthy elderly population. J Gerontol 1987;42:345-6.

- Nelson HE. A modified card sorting test sensitive to frontal lobe defects. Cortex 1976;12:313-24.

- Robinson LJ, Kester DB, Saykin AJ, Kaplan EF, Gur RC. Comparison of two short forms of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Arch Clin Neuropsychol 1991;6:27-33.

- Royall DR, Mahurin RK, Gray Bedside assessment of executive cognitive impairment: the executive interview. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992;40:1221-6.

- Anthony JC, LeResche L, Niaz U, von Korff MR, Folstein Limits of the ‘Mini-Mental State’ as a screening test for dementia and delirium among hospital patients. Psychol Med 1982;12:397-408.

- Nelson A, Fogel BS, Faust Bedside cognitive screening instruments. A critical assessment. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986;174:73-83.

- Chan SM, Chiu FK, Lam CW. Correlational study of the Chinese version of the executive interview (C-EXIT25) to other cognitive measures in a psychogeriatric population in Hong Kong Chinese. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;21:535-41.

- Chan CW, Lam LC, Wong TC, Chiu Modified Card Sorting Test Performance among community dwelling elderly Chinese people. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2003;13:2-7.

- de Zubicaray GI, Smith GA, Chalk JB, Semple J. The Modified Card Sorting Test: test-retest stability and relationships with demographic variables in a healthy older adult sample. Br J Clin Psychol 1998;37:457-66.

- Chiu HF, Lee H, Chung WS, Kwong PK. Reliability and validity of the Cantonese version of MMSE — a preliminary study. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 1994;4:25-8.

- Chan AS, Choi A, Chiu H, Lam L. Clinical validity of the Chinese version of Mattis Dementia Rating Scale in differentiating dementia of Alzheimer’s type in Hong Kong. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2003;9:45-55.

- Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin Anew clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry 1982;140:566-72.

- Morris JC, Storandt M, Miller JP, McKeel DW, Price JL, Rubin EH, et al. Mild cognitive impairment represents early-stage Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2001;58:397-405.

- de Zubicaray GI, Ashton R. Nelson’s (1976) Modified Card Sorting Test: a review. Clin Neuropsychol 1996;10:245-54.