Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2009;19:112-6

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

圍產期的焦慮及抑鬱症狀:轉介至香港一所地區醫院的綜合兒 童發展服務的個案

姚家聰、司徒偉倫、黃碧君、苗延瓊

Dr Michael GC Yiu, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Kowloon East Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, China.

Mr Wai-lun Szeto, BSc in Nursing (Hons), Master in Primary Health Care, Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, China.

Ms Gillian PK Wong, BSc in Nursing (Hons), Advanced Practice Nurse (Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, United Christian Hospital, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, China.

Dr May YK Miao, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Kowloon East Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr May YK Miao, Department of Psychiatry, Comprehensive Child Development Service (CCDS), United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

Tel: (852) 2727 8350; Fax: (852) 2348 8315; E-mail: miaoyk@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 16 October 2008; Accepted: 2 February 2009

Abstract

Objectives: To review the demographic profiles of new psychiatric referrals to the Comprehensive Child Development Service of a regional hospital in Hong Kong and study their psychiatric diagnostic profiles.

Participants and Methods: Consecutive patients referred to the Comprehensive Child Development Service from October 2006 to July 2008 were enrolled. Psychiatric diagnosis was made by a specialist psychiatrist, according to the International Classification of Diseases – 10th Revision. Antenatal and postnatal patients were studied separately. With regard to the 2 major diagnostic groups (depressive and anxiety disorders), risk factors — including marital status, unplanned pregnancy, maternal psychiatric history, personal psychiatric history, and complications in previous pregnancies — were analysed and compared.

Results: A total of 181 cases referred to psychiatry were included; 24 (13%) were antenatal, while 157 (87%) were postnatal. There were 2 main diagnostic groups, namely patients with depressive spectrum disorder and anxiety spectrum disorder. Among the 24 antenatal patients, 17 (71%) had anxiety, and 4 (17%) had depressive spectrum disorder. Among the 157 postnatal patients, 67 (43%) had depressive spectrum symptoms and 76 (48%) had anxiety spectrum symptoms.

Conclusions: The impression that depressive disorder was the only significant mental disorder of pregnancy in the perinatal period needs further evaluation. A high percentage of patients suffered anxiety spectrum disorders during the perinatal period. Screening, early detection, and effective intervention for anxiety disorders should also be an important component of the Comprehensive Child Development Service programme.

Key words: Anxiety disorders; Depression, postpartum; Pregnancy; Perinatal care

摘要

目的:回顧新轉介至香港一所地區醫院的綜合兒童發展服務的個案的人口學資料,和探討這些個案的精神診斷資料。

參與者與方法:參與者包括在2006年10月至2008年7月期間,被轉介至綜合兒童發展服務的人仕。精神科醫生根據國際疾病分類ICD-10編碼作出臨床診斷。本研究分別探討產前及產後的病人。對於分別有焦慮及抑鬱症的兩組病人,會分析及比較其風險因素,包括婚姻狀況、是否意外懷孕、孕婦的家族精神紀錄、個人的精神紀錄,以及過往妊娠有否出現併發症。

結果:被轉介的個案共有181個,包括24個(13%)產前病人和157個(87%)產後病人。個案可分為抑鬱症及焦慮症兩種。24位產前病人中,17位(71%)有焦慮症,4位(17%)有抑鬱症。157位產後病人中,67位(43%)有抑鬱症,76位(48%)有焦慮症。

結論:過往認為圍產期中抑鬱症是唯一具影響的疾病這種看法需要作進一步的檢討。事實上,圍產期內也會出現高比率的焦慮症。篩檢、盡早監測,以及有效地處理焦慮症是綜合兒童發展服務不可或缺的。

關鍵詞:焦慮症、產後抑鬱症、妊娠、圍產期的護理

Introduction

Childbirth is one of the most complicated events in human experience in terms of biological, psychological, and social perspectives. Childbirth is viewed by society as a joyful event. However the real experiences of mothers are often more complex than this idealized image. Instead of the expected fulfilment and tranquility, many women struggle with new sets of demands and expectations, loss of order and routine, feelings of being ‘trapped’, and having to endure sleepless nights. The transition in their role to the parenthood may also involve changes in relationships with their partners, career decisions, and social isolation. Other challenges may involve financial distress and housing problems (especially when a pregnancy is unplanned). The stresses and emotional upheaval in vulnerable women may predispose them to psychiatric morbidity.

Most reports regarding psychiatric disturbances in the postpartum period fall into 3 groups — postpartum blues, postpartum depression, and postpartum psychosis. Some of the disturbances are part of what may be termed general psychiatric disorders, but some may be closely related to the reproductive process. Apart from the postpartum psychosis, other non-psychotic disorders are commonly subsumed under the rubric of antenatal and postnatal depression. There are dangers of grouping diverse disorders under a single heading.1 Some studies show that anxiety disorders may be more common than depression.2-4 Anxiety disorders in pregnancy and childbirth have a specific focal content, for which specific interventions may be indicated.5

The focus of antenatal anxiety could be: fear of foetal abnormality, fear of foetal loss (especially after previous reproductive difficulties and losses),6 fear of stillbirth, fear of childbirth, and fear of inadequacy as a mother. The focus of postnatal anxiety could be: fear of the newborn, based on the awesome responsibility of care7; some mothers develop infant-focused anxiety, or obsessive impulses and thoughts, with phobias about the baby.8 Fear of cot death could result in exhausting nocturnal vigilance.9 Moreover, many mothers are excessively troubled about the health and safety of their children.

One in 10 women suffer from postnatal depression (PND) without psychotic features.10 Prevalence rates vary depending on the population studied, the method of assessment, and the length of the postpartum period under evaluation. A striking feature of PND is that it impacts both mother and infant. Its effects include cognitive and social difficulties, difficulty in attachment and infant development. All such adverse effects may persist even after resolution of maternal symptoms.11 Postnatal depression also affects relationship with the partner, and appears to exacerbate problems that existed before the pregnancy, since a poor marital relationship has been described to be a risk factor for PND.12

Relatively little attention has been given to the relationship between anxiety disorders and childbirth. The 2 conditions frequently co-exist.13 It is highly likely that many women who report depression in the postpartum period also experience clinically significant levels of anxiety. Recent studies suggest that postpartum anxiety disorders are underestimated and are more common than depression.14-18 A prospective study demonstrated that nearly 20% of postpartum women reporting dysphoria also experience panic and / or obsessive compulsive symptoms.19 Anxiety appears to be a common experience in women who are 4 to 6 months postpartum.19 There could be a biological basis for some postpartum anxiety. Mc Ivor and colleagues20 studied the growth hormone response to apomorphine (a test of D2 receptor sensitivity) in 14 puerperal women with a history of depression. The greatest increase in receptor sensitivity was found in the 3 women who developed postpartum anxiety disorders.

Women exhibit increased levels of cortisol during pregnancy and at the beginning of the postpartum period.21 Carlson22 reported that anxiety symptoms and stress often co-exist with increased cortisol levels. Pregnant women with co-morbid anxiety and depression — but not depression alone — have elevated cortisol levels; such co-morbidity being particularly associated with negative pregnancy- specific experiences.23

Postnatal depression and ‘postnatal blues’ were perceived as common pregnancy-related psychiatric disorders. Such emphasis needs to be carefully evaluated.

Methods

Consecutive cases referred to the psychiatrist of the Comprehensive Child Development Service (CCDS) from October 2006 to July 2008 were assessed and recruited into the study. The specialist psychiatrist conducted a clinical interview for each subject. All participants were categorised according to the International Classification of Diseases – 10th Revision (ICD10) into different psychiatric diagnoses. Demographic factors and potential risk factors were recorded on a data sheet, including: marital status, planned or unplanned pregnancy, maternal family history of psychiatric illness, history of psychiatric illness,10,24 history of miscarriages and stillbirths, history of termination of pregnancy, treatment history for infertility25,26 and psychiatric complications during pregnancy.27

Statistical Analysis

Subjects were grouped into antenatal and postnatal subgroups. In each subgroup, the risk factors for anxiety spectrum versus depressive spectrum disorder were analysed. The Chi-square test was used to compare categorical data for the groups. Student’s t test (for parametric data) and the Mann-Whitney U test (for non-parametric data) were employed to compare corresponding numerical data. A p value of less than 0.05 was taken as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows version 13.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US).

Results

A total of 181 cases referred to the psychiatrist were included; 24 (13%) were antenatal, and 157 (87%) postnatal (Table 1).

The majority of antenatal cases were referred by Department of the Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the United Christian Hospital (67%). The main source of referral for postnatal cases was from Maternal and Child Health Centres (MCHCs) of the Department of Health (59%). In both antenatal and postnatal groups, the majority of subjects were permanent residents of Hong Kong (75% for both); corresponding figures for new immigrants (mainly from Mainland China) were 13% and 20%.

Profiles of Psychiatric Diagnoses

Two main diagnostic groups emerged: (1) depressive spectrum group (depressive episode and recurrent depressive episodes) and (2) anxiety spectrum group (phobic anxiety, other anxiety disorders — panic disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, and mixed anxiety and depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and reaction to stress). In the antenatal group, 4 (17%) belonged to the depressive spectrum group and 17 (71%) were in the anxiety spectrum group. In the postnatal group, 67 (43%) to the depressive spectrum group and 76 (48%) belonged to the anxiety spectrum group (Table 2).

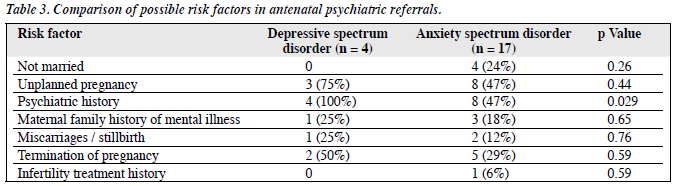

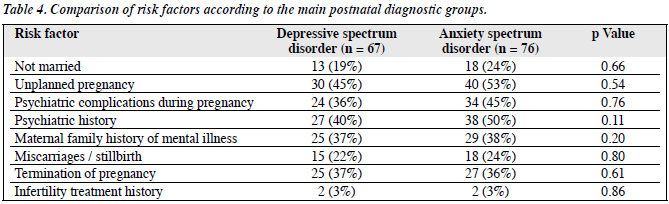

In the antenatal group, there was a higher prevalence of subjects with a depressive spectrum psychiatric history (p = 0.029), all of whom had suffered past depressive episodes. There were no other statistically significant differences in risk factor profiles between these 2 major diagnostic groups among the antenatal and postnatal cases (p > 0.05; Tables 3 and 4).

Discussion

In our study, anxiety symptoms appeared to be more common during pregnancy and equally common after delivery, suggesting that pregnancy-related anxiety disorders should not be neglected. In another cohort study using serial self- reported measures, anxiety was more common during pregnancy, but depression was commoner after delivery.28 It has also been reported that antenatal anxiety was an independent predictor of postpartum depression.29

There is a well-established overlap between anxiety disorders and depressive syndromes. Panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, and post- traumatic disorder have all been demonstrated to have significant co-morbidity with depression. The difficulty in distinguishing anxiety disorders from depression in pregnant women has been demonstrated, although very few self-report screening inventories for anxiety disorders were found to be sensitive or reliable.30 Anxiety disorders are symptomatically similar to depressive disorders; they share common vulnerability factors and many of the treatments for both sets of disorders are similar. This study reflects no major difference in risk factors between anxiety and depressive spectrum disorders for both the antenatal and postnatal groups.

That the clinical diagnosis was based on clinical judgement according to ICD10 is a limitation of the present study. For more robust diagnostic validity, we should use a structured diagnostic interview, such as the Structured Clinical Interview of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual – IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). Co-morbidities and Axis II diagnoses were not assessed. The patients were referred to a specialist service and therefore likely to be suffering more severe disorders. Most of the referrals were screened in the MCHCs, either by psychiatric nurses or on-site psychiatrists. The majority of patients with milder problems were managed by nurses and doctors in the MCHCs. The lack of subjects with no psychiatric diagnosis upon assessment at CCDS indicated that all these referred patients were more severely affected. Our sample size, especially for the antenatal group, was small. We grouped several different entities under 2 common and major diagnostic groups, and thus the heterogeneous arrays of perinatal psychiatric conditions were not separately and discretely studied.

The impression of depressive disorders as the only significant mental disorder of pregnancy and the perinatal period is probably an oversimplification. In this study sample, there was a notably higher proportion than commonly perceived who suffered from anxiety spectrum disorder during the pregnancy and the postnatal period. The implications of these results are significant, because little attention has been given to peripartum anxiety. Women experiencing clinically significant generalised anxiety symptoms during pregnancy and following childbirth are not being identified and referred to appropriate mental health services. In the future, it is important to map the precise course of anxiety and depression during the whole of pregnancy as well as post-delivery. It would be useful to identify risk factors, so that vulnerable women could be identified and provided timely services. It is also important for future research to investigate whether existing treatments for anxiety disorders are equally applicable in this particular population.

Screening, detection, and interventions to deal with anxiety disorders in the perinatal period should be an important component of further research and development for the CCDS programme.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Chung-ming Chu of the United Christian Hospital for his advice on statistical analysis.

References

- Brockington IF. Book forum. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:2.

- Matthey S, Barnell B, Howie P, Kavanagh DJ. Diagnosing postpartum depression in mothers and fathers: whatever happened to anxiety? J Affect Disord 2003;74:139-47.

- Ross LE, Gilbert Evans SE, Sellers EM, Romach MK. Measurement issues in postpartum depression part 1: anxiety as a feature of postpartum depression. Arch Womens Ment Health 2003;6:51-7.

- Wenzel A, Haugen EN, Jackson LC, Brendle JR, Anxiety symptoms and disorders at eight weeks postpartum. J Anxiety Disord 2005;19:295- 311.

- Brockington IF, Macdonald E, Wainscott G. Anxiety, obsessions and morbid preoccupations in pregnancy and the puerperium. Arch Womens Ment Health 2006;9:253-63.

- Heymans H, Winter ST. Fears during pregnancy. An interview study of 200 postpartum women. Isr J Med Sci 1975;11:1102-5.

- De Armond M. A type of post partum anxiety reaction. Dis Nerv Syst 1954;15:26-9.

- Sved-Williams AE. Phobic reactions of mothers to their own babies. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1992;26:631-8.

- Weightman H, Dalal BM, Brockington IF. Pathological fear of cot death. Psychopathology 1998;31:246-9.

- O’Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression: a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 1996;8:37-54.

- Murray L, Fiori-Cowley A, Hooper R, Cooper P. The impact of postnatal depression and associated adversity on early mother-infant interactions and later infant outcome. Child Dev 1996;67:2512-26.

- Milgrom J, McCloud PI. Parenting stress and postnatal depression stress medicine. Stress Med 1996;12:177-86.

- Maser JD, Cloninger CR. Comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1990.

- Hertzberg T, Wahlbeck K. The impact of pregnancy and puerperium on panic disorder: a review. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 1999;20:59- 64.

- Button JH, Reivich RS. Obsessions of infanticide. A review of 42 cases. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1972;27:235-40.

- Chapman AH. Obsessions of infanticide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1959;1:12-6.

- Burttolph ML, Holland AD. Obsessive compulsive disorder in pregnancy and childbirth. OCD: theory and management. 2nd ed. Chicago: Year book Medical Publishers; 1990: 89-95.

- Wenzel A, Haugen EN, Jackson LC, Robinson K. Prevalence of generalized anxiety at eight weeks postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health 2003;6:43-9.

- Wenzel A, Gorman LL, O’Hara MW, Stuart S. The occurrence of panic and obsessive compulsive symptoms in women with postpartum dysphoria: a prospective study. Arch Womens Ment Health 2001;4:5- 12.

- Mc Ivor RJ, Davies RA, Wieck A, Marks MN, Brown N, Campbell IC, et al. The growth hormone response to apomorphine at 4 days postpartum in women with a history of major depression. J Affect Disord 1996;40:131-6.

- O’Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Varner MW. Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders: psychological, environmental, and hormonal variables. J Abnorm Psychol 1991;100:63-73.

- Carlson NR. Physiology of behavior. 7th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2001.

- Evans LM, Myers MM, Monk C. Pregnant women’s cortisol is elevated with anxiety and depression — but only when comorbid. Arch Womens Ment Health 2008:11:239-48.

- Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004;26:289-95.

- Kumar R, Robson KM. A prospective study of emotional disorders in childbearing women. Br J Psychiatry 1984;144:35-47.

- Elliott SA. Pregnancy and after. In: Rachman S, editor. Contributions to medical psychology. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1984: 93-116.

- Heron J, O’Connor TG, Evans J, Golding J, Glover V; The ALSPAC Study Team. The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. J Affect Disord 2004;80:65- 73.

- Sutter-Dallay AL, Giaconne-Marcesche V, Glatigny-Dallay E, Verdoux H. Women with anxiety disorders during pregnancy are at increased risk of intense postnatal depressive symptoms: a prospective survey of the MATQUID cohort. Eur Psychiatry 2004;19:459-63.

- Muzik M, Klier CM, Rosenblum KL, Holzinger A, Umek W, Katschnig H. Are commonly used self-report inventories suitable for screening postpartum depression and anxiety disorders? Acta Psychiatric Scand 2000;102:71-3.

- Stuart S, Couser G, Schilder K, O’Hara MW, Gorman L. Postpartum anxiety and depression: onset and comorbidity in a community sample. J Nerv Ment Dis 1998;186:420-4.