Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2008;18:123-5

CASE REPORT

氟西汀與鋰的結合療法引致的血清素症候群

Dr R Mahendran, MB, BS, M Med (Psych), FAMS, Clinical Associate Professor, Institute of Mental Health/Woodbridge Hospital, Singapore.

Address for correspondence: Clin A/Prof R Mahendran, Institute of Mental Health/Woodbridge Hospital, 10, Buangkok View, Singapore 539747.

Tel: 65 6389 2000; Fax: 65 6385 5900;

E-mail: rathi_mahendran@imh.com.sg

Submitted: 12 March 2008; Accepted: 2 May 2008

A rare presentation of the serotonin syndrome occurred following the use of a fairly common combination of the antidepressant fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and lithium carbonate, a mood-stabiliser. The syndrome is characterised by a sudden onset of mental state changes, autonomic instability, and increased neuromuscular activity. Recovery occurred after discontinuation of the drug combination. The mood symptoms were subsequently treated with an atypical antipsychotic. Fatalities and complications may be associated with the serotonin syndrome. A detailed medication history, awareness of the syndrome, and early recognition are crucial for effective management.

Key words: Antidepressive agents; Drug interactions; Mental disorders; Serotonin uptake inhibitors

結合使用抗抑鬱藥氟西汀和情緒穩定劑碳酸鍊鋰(一種選擇性血清素調節劑) 的療法相當普遍。本文報告由這種結合療法引致血清素症候群的罕見病。血清素症候群的特徵是突發的精神狀態改變、自律神經失調,以及神經肌肉活動增加。病人停止服用藥物後,徵狀減退,再接受非典型抗精神病藥物來治療情緒改變。血清素症候群可能引致併發症甚至死亡。詳細的用藥史、對此病的認識,以及早診斷都是獲得良好療效的關鍵。

關鍵詞:抗抑鬱藥劑、藥物相互作用、精神異常、血清素回收抑制劑

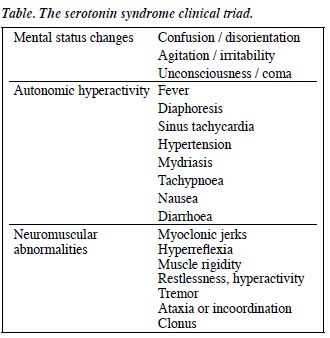

Serotonin syndrome is a potentially fatal condition that presents with psychiatric and neurologic symptoms arising from a hyperserotonergic state. The serotonin elevation has a dose-effect on the severity of serotonergic symptoms.1 The syndrome was initially identified in animal studies; the first human cases were reported in the 50s.2,3 The serotonin syndrome is described as a clinical triad of mental state disturbances, autonomic hyperactivity, and neuromuscular abnormalities (Table)4 but these features are not always consistently present in every patient.

There is still a lack of awareness and recognition of the syndrome mainly because of its rarity. A PubMed search revealed 3 case reports of serotonin syndrome with the fluoxetine / lithium combination.5-7 In a fourth case report the serotonin syndrome was precipitated by dextromethorphan abuse in a patient treated with fluoxetine and lithium.8 All these cases involved Caucasian patients and the 2 cases published in English were female patients, one a 36-year- old and the other a 61-year-old.5,7 We report a case in a male Chinese patient who developed the serotonin syndrome while on treatment with fluoxetine and lithium carbonate, in order to highlight the syndrome’s features and demonstrate how it may mimic several other conditions.

Case Report

A 53-year-old male presented in December 2006 to a psychiatric hospital with a 3-week history of low mood, poor sleep and appetite, weight loss, and thoughts that his life was meaningless and empty. He also reported auditory hallucinations and persecutory ideas that were mood- congruent. There was no psychiatric history or history of medical or surgical illnesses. There was no history of illicit substance or alcohol use and no history of self-medication. There were no significant findings on physical examination and his baseline haematology, renal and thyroid function tests were within normal limits. He was diagnosed with a first episode of a major depressive disorder, moderate with psychotic features.9

He was started on dothiepin (75 mg at night) and sodium valproate (400 mg at night). His condition worsened and he became withdrawn and uncommunicative and developed further loss of appetite. After 2 days, the sodium valproate was stopped and replaced with lithium carbonate (400 mg at night) that was increased to 600 mg the following day. On the fifth day, the dothiepin was stopped and the treating team added fluoxetine 20 mg per day to the lithium carbonate.

By the next day he was found to be slightly stiff with tremors. He was disorientated, confused, and restless. His blood pressure, which had been within the normal range, increased to 140/100 mm Hg and his pulse rate was 90 beats per minute. His mood was still depressed, and he became increasingly irritable. The confusion and restlessness persisted. He was nursed intensively with supervision of his activities of daily living and monitoring of mental state and vital parameters. Over the next 3 days his blood pressure fluctuated between 130/80 and 180/100 mm Hg. He spiked a fever of 38.5°C and was sweating and restless. Muscle rigidity was noted, accompanied by hyperreflexia, clonus, and occasional twitching of his limbs.

Repeated haematology and biochemistry, urine tests and serial creatinine kinase levels were normal and the serum lithium was within normal limits (< 0.5 mEq/L). There was no evidence of a septic cause. An electrocardiogram and chest X-ray were normal. Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed no organic or structural abnormalities. By the fourth day, the differential diagnoses being considered included serotonin syndrome and catatonia. The former was considered the most likely based on the clustering of signs and symptoms, medication used and the chronological sequence of events and duration. All the medications were stopped and he was continuously monitored and given supportive measures such as hydration. His condition stabilised rapidly over the next 5 days but his mood was increasingly depressed and he was still experiencing auditory hallucinations, so he was started on low doses of an atypical antipsychotic (olanzapine). There was no recurrence of any physical symptoms and his mood eventually improved with appropriate dose titration.

On reviewing his history, it was evident that he had serotonin syndrome. He had not received any antidopaminergic agents. Both fluoxetine and lithium carbonate are medications that have been associated with the serotonin syndrome and there is evidence that lithium may actually increase the risk of the syndrome when administered with serotonergic agents.10,11

Discussion

While the serotonin syndrome has traditionally been described with proserotonergic drugs, this patient’s condition was precipitated by a combination of medications that, although associated with an increased risk, is infrequently seen. A confounding issue was the use of a mood stabiliser and an antidepressant, despite practice guidelines recommending the combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic for a major depressive disorder with psychotic features.12 The rapid medication switches and dose escalations may have increased the risk. Common medical conditions known to increase the risk of serotonin syndrome, such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, hypercholesterolaemia, and damaged vascular or pulmonary endothelium were not present in this patient.13

The serotonin syndrome can present with a range of symptoms, both varied and non-specific, and ranges in degree from mild to severe states. This can contribute to diagnostic difficulties. Neuromuscular symptoms and clonus in a patient being treated with serotonergic drugs are highly diagnostic. These features became the Sternbach criteria following a review of a small series of cases presenting with serotonin syndrome.11 The Sternbach criteria also requires exclusion of other medical conditions and antidopaminergic drug use. More recently the Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria14 has listed clinical findings with statistically significant associations with serotonin syndrome. These are primarily neuromuscular including hyperreflexia, clonus (inducible, spontaneous and ocular), myoclonus, peripheral hypertonicity, and shivering. Autonomic states listed include tachycardia, mydriasis, diaphoresis, diarrhoea, and the presence of bowel sounds. Mental state changes were agitation and delirium.14 The case reported here meets these diagnostic criteria.

The underlying pathophysiology in serotonin syndrome is enhanced serotonin neurotransmission and stimulation of central and peripheral serotonin receptors.15 The actual incidence of serotonin syndrome remains unknown. The use of combination therapy, augmentation strategies, and pharmacokinetic interactions that increase serotonergic stimulation increase the risk. A recent report linked 146 cases of serotonin syndrome with the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and it reportedly occurs in 14 to 16% of people who overdose with SSRIs.16,17 Some thus refer to it as serotonin toxicity to emphasise this dose relationship and poisoning from ingestion of the medication. The onset is usually rapid — less than an hour in cases of self-poisoning — but there are also reports of delayed onset occurring several weeks after the addition of another medication.18

The differential diagnosis for serotonin syndrome includes the anticholinergic syndrome, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and malignant hyperthermia. In this patient, catatonia with depression was a serious consideration. The clinical picture in those with catatonic features include: (1) motor immobility manifested as catalepsy or stupor, (2) excessive motor activity, (3) extreme negativism, (4) peculiarities of voluntary movement manifested as posturing, stereotypical movements, and (5) echolalia or echopraxia.9 The clinical presentation and the recovery on withdrawal of fluoxetine and lithium made catatonia an unlikely primary diagnosis.

The anticholinergic syndrome results from poisoning with an anticholinergic agent. The clinical presentation is somewhat similar to the serotonin syndrome in the autonomic changes of hypertension, tachycardia, tachypnoea, and hyperthermia but the patient’s skin is erythematous, hot and dry, bowel sounds are decreased and absent, and there are no neuromuscular abnormalities.14 The neuroleptic malignant syndrome is an idiopathic reaction to dopamine antagonist medication which produces bradykinesia over a few days.19 Symptoms such as altered consciousness, diaphoresis, hyperthermia, and autonomic changes are shared with the serotonin syndrome but the neuromuscular changes in neuroleptic malignant syndrome include ‘lead-pipe’ rigidity in all muscle groups with bradyreflexia. In addition, a marked elevation of creatinine kinase and leukocytosis are characteristic of the neuroleptic malignant syndrome and absent in serotonin syndrome.20 It has been suggested that both these conditions may not be specific syndromes but rather part of a non-specific generalised neurotoxic syndrome and subtypes of catatonia.21 Lastly, malignant hyperthermia is a pharmacogenetic disorder related to inhalational anaesthesia or succinylcholine use. Autonomic changes are present but the skin has a distinctive mottled appearance with rigor mortis-like rigidity and hyporeflexia.

Management of the serotonin syndrome involves immediate discontinuation of suspected medications, supportive care, control of autonomic instability and hyperthermia, control of agitation and, if needed, the use of serotonin antagonists such as cyproheptadine.14 Up to 70% of cases recover within 24 hours but symptoms may persist longer in those patients who have received drugs with long elimination half-lives or active metabolites.10 Although this patient recovered from the serotonin syndrome, fatalities and complications including disseminated intravascular coagulation, rhabdomyolysis, hypotension, and acute renal failure have been reported.22

Physicians need to be aware of this syndrome in order to recognise it early and manage it effectively. Better prescription practices, particularly avoiding polypharmacy and recognising that those patients who need combination or augmentation strategies must be closely monitored and followed, are required.23 A thorough medication history from patients is crucial as over-the-counter medications, illicit substances, and dietary supplements have also been implicated in the serotonin syndrome.24

References

- Gillman PK. Understanding toxidromes: serotonin toxicity: a commentary on Montanes-Rada et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2005;25:625-6.

- Bogdanski DF, Weissbach H, Udenfriend S. Pharmacological studies with the serotonin precursor, 5-hydroxytryptophan. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1958;122:182-94.

- Gillman PK. Serotonin syndrome: history and risk. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 1998;12:482-91.

- Martin TG. Serotonin syndrome. Ann Emerg Med 1996;28:520-6.

- Muly EC, McDonald W, Steffens D, Book S. Serotonin syndrome produced by a combination of fluoxetine and lithium. Am J Psychiatry 1993;150:1565.

- Karle J, Bjorndal F. Serotonergic syndrome — in combination therapy with lithium and fluoxetine [in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger 1995;157:1204-5.

- Loza B. A case of serotonin syndrome [in Polish]. Psychiatr Pol 1995;29:529-38.

- Navarro A, Perry C, Bobo WV. A case of serotonin syndrome precipitated by abuse of the anticough remedy dextromethorphan in a bipolar patient treated with fluoxetine and lithium. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2006;28:78-80.

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM IV TM. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1112-20.

- 1 Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1991;148:705- 13.

- Andreescu C, Mulsant BH, Peasley-Miklus C, Rothschild AJ, Flint AJ, Heo M, et al. Persisting low use of antipsychotics in the treatment of major depressive disorder with psychotic features. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:194-200.

- Brown TM, Skop BP, Mareth TR. Pathophysiology and management of the serotonin syndrome. Ann Pharmacother 1996;30:527-33.

- Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, Dawson AH, Whyte IM. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM 2003;96:635-42.

- Sternbach H. Serotonin syndrome: how to avoid, identify and treat dangerous drug interactions. Current Psychiatry 2003;2:124-6.

- Montanes-Rada F, Bilbao-Garay J, de Lucas-Taracena MT, Ortiz-Ortiz ME. Vanlafaxine, serotonin syndrome, and differential diagnoses. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2005;25:101-2.

- Isbister GK, Bowe SJ, Dawson A, Whyte IM. Relative toxicity of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in overdose. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2004;42:277-85.

- von Halling Laier MG, Gram LF. Serotonin syndrome and malignant neuroleptic syndrome. A review based on the material from the National Board of Adverse Drug Reactions [in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger 1996;158:6933-7.

- Guzé BH, Baxter LR Jr. Current concepts. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. N Engl J Med 1985;313:163-6.

- Levenson JL. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1985;142:1137-45.

- Fink M. Toxic serotonin syndrome or neuroleptic malignant syndrome? Pharmacopsychiatry 1996;29:159-61.

- Rosebush P, Garside S, Levinson A, Schroeder JA, Richards C, Mazurek M. Serotonin syndrome: a case series of 16 patients. Ann Neurol 2002;52:554.

- Baubet T, Peronne E. Serotonin syndrome: critical review of the literature. Rev Med Interne 1997;18:380-7.

- Lane R, Baldwin D. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced serotonin syndrome: review. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997;17:208-21.