J.H.K.C. Psych. (1993) 3, 19-27

SPECIAL TOPIC: CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

Summary

This study aims at exploring the problem of suicide among children and youths under 21 in Hong Kong in the past 10 years (1981-1990) by reviewing the coroner's reports. The suicide rate for age group 10-20 is found to be 2.2 per 100,000. Although the phenomenon is not as serious as in other countries such as Japan and the U.S.A., it has caused great concern to the public. Unfortunately, the nature of the problem, especially its causes, has been in a certain extent distorted by the public. Certainly, the school should not be the only system in which various kinds of effort are to be put to prevent suicide among children and youths. The deteriorating family structure in Hong Kong deserves equal and even more attention.

INTRODUCTION

Various means of escape from the unpleasant reality have been learned by people in their upbringing. Suicide, the most irreversible escape, appears to have increased disturbingly among teenagers during the past two or three decades in most countries.

A teenager's suicide is always shocking. It will distress those who know him and very often it captures headlines. Relatives and journalists would often depersonalize the death and seek an explanation for it by blaming the changing society or attribute it to a deteriorating educational system. The publicity given to individual incident may lead many to conclude that childhood and adolescent suicide is an overlooked and growing phenomenon. Although such conclusion has gained empirical support in the West, statistical in Hong Kong can hardly be found. The present study aimed to explore the scope of the problem in Hong Kong during the past ten years.

LITERATURE REVIEW

DURKHEIM'S CLASSIC STUDY

The study of suicide against its social background may be dated from the classic research of Durkheim, first published in 1897. He defined suicide as death resulting from behavior that the individual knows will lead to his own demise. Whether death is desired is immaterial and only the individual's awareness of the consequences of his behavior is relevant (Durkheim, 1951).

Durkheim investigated not suicides per se but social suicide rates. His study focused on comparisons and tried to explain why the rate was higher for one group than the other. With the support of the rates he collected, Durkheim argued that suicide rate was a measure of the health of the social body. He also generated a strictly sociological theory of suicide by identifying two major explanatory variables, integration and regulation, that created his four types of suicide: egoistic, altruistic, anomic, and fatalistic. He observed that whenever integration or regulation was strong or weak, the suicide rate was high; whenever moderate, the rate was low as shown below in Figure 1.

CONCEPT OF DEATH AMONG CHILDREN AND YOUTHS

There is a fundamental question before one goes on to make any further enquiries concerning suicide among children and adolescents: what do children know of death? Children's views of life and death differ sharply from adult views. In an early study on this subject, Gesell and Ilg (1946) presented a dynamic approach that considered both cognitive change and the parallel emotional reactions. The central conclusion was that the main bulk of development in grappling with death occurred by age seven, and by age twelve, there was a clear understanding of the distinctive appearance of the dead compared to the living.

Similarly, Kane (1979) also described the development of the concept of death among children in three stages. Initially, a child could only perceive death as a separation and lack of movement. Secondly, all aspects of death seemed to be understood but only in concrete terms. Finally, during the last stage, these aspects would be known on a more abstract level.

Despite popular beliefs, children's suicide does not seem to be the result of misunderstanding. Orbach (1988) argued that both cognitively and emotionally, the suicidal appeared to have ample grasp of the true meaning of their actions. The suicidal understand the finality of death, just as others do. Therefore, it would be wrong to view their acts as games with tragic consequences or accidents with no agent. In fact, death is viewed as a possible alternative to the here and now by the suicidal.

FAMILIAL FACTORS

Being the first and the most closed institution one attached to in childhood, family is found to be the source of most factors leading to children and adolescent suicide. People used to mention some specific factors in family life, such as the death of a family member, divorce and separation, neglect and abuse, and family aggression, sensitizing self-destruction. However, Orbach (1988) had identified three types of families that most suicidal come from.

Multiple-problem family

The first type is termed the "multiple-problem family". The series of grave problems and crises emerged in this kind of family not only disintegrated the whole family but also disrupted the child's normal growth and denied the fulfillment of even basic needs. Eventually, suicide becomes an outcome of the continual pressures engendered by a variety of long-standing difficulties covering a range of areas. These pressures, rather than any single event or factor, leads to family disintegration and the growth of destructive family patterns. Obviously, the ongoing family chaos continually wears down the child's ego functioning and ability to cope. It may also hinder normal emotional development and damage self-esteem.

Deadly message family

The second type is characterized by the "deadly message" that family members broadcast to the potential victim. This message was regarded as part of an unconscious plan to rid the family of an unwanted or scape-goated child. Clinical observers (Sabbath, 1969; Glaser, 1965; Gould, 1965; Toolan, 1962) reported that suicidal children had frequently experienced strong parental rejection. This rejection used to begin early in life and could even arise before the child was born. Among parents trapped into parenthood, the tragic feeling that "maybe it would have been better if he weren't born at all" echoed for years.

The deadly message is earmarked by dramatic and repugnant elements: rejection, hostility, isolation, and scapegoating. Against this background, the child gets the message that he must leave. Hints of death point him in the desired direction. In this light, the child's suicide can be said as an ultimate submission to parental will.

Symbiotic family

This type of family may be admired by others at first sight by its apparent harmony. Symbiosis is originally used to described a state where a strong mutual bond exists between a mother and child, so that each is abnormally dependent on the other. Similarly, a symbiotic family has a massive generalized identity, with little distinction among the different members. All seem to be parts of one larger whole. Each member feels complete only through the emotional mix with the others. In this extreme drive for unity, members of symbiotic families are often left with the paradoxical feeling of isolation and loss of self. At the same time, symbiotic parents perceive their strong emotional demand as expressions of loyalty and love but frequently do not even allow their children to express their feelings. It is a process of deindividualisation which is extremely harmful to any adolescents in search of self-identity. The suicide resulted is, to a certain extent, an example of Durkheim's fatalism mentioned before.

All these three approaches focus on the characteristics of the suicidal person's family. However, familial factors have rarely been focused in investigating children and adolescents suicide in Hong Kong. Most efforts have been made in looking into the school life of the suicidal.

METHOD OF STUDY

SOURCE OF INFORMATION

The Coroner's Court is a valuable source to study the demographic and related variables of suicide as it has all the suicide cases kept in register. It is undoubtedly a valuable source of information concerning successful suicide of the whole territory of Hong Kong. Because of some administrative limitations, only coroner's reports for suicidal teenagers under 21 at their deaths between 1986 and 1990 were studied. For those cases from 1981 to 1985, demographic data were calculated from the Coroner's Case Register.

LIMITATION OF THE STUDY

Limitations exists in studying the problem by referring to the coroner's reports. Basically, the reports were not prepared for research purpose. They aimed at establishing the verdict for the death. As a result, the reports would only record those information the investigation officer thought useful. Facts concerning the family structure or revealing interaction among family members were rarely mentioned. Moreover, what the reports recorded were just the information known by the court. For instance, the fact that there were no record about the leaving of a suicide note did not mean that such a note did not exist. Despite that, the Coroner's Court is undoubtedly the most reliable source of information concerning successful suicide of the whole territory of Hong Kong.

DEFINITION OF SUICIDE

With regard to the present study, suicide is a legal verdict which has to be established only by the court through due process. Content analysis of the coroner's reports in this study revealed that, in Hong Kong, suicide verdicts used to be reached upon the discovering of one or more of the following factors:

- Witnesses testified to the death act. The deceased might have been seen by a witness near the scene of the act. Often a witness testified that he saw the deceased climbing onto a chair or coming out on a balcony before jumping or falling. The presence of an eye-witness is always considered as one of the powerful factors in supporting a suicide verdict.

- The deceased left a suicide note stating that he or she had committed suicide or that the intent was to commit suicide.

- There was a history of past attempt or attempts

- There was a history of disturbed mental condition showing that the deceased was depressed because of distressing or shameful circumstances

- The deceased was suffering from severe mental illness such as schizophrenia or agitated depression.

- The deceased had a painful, incapacitating, or incurable physical illness.

- Evidence was given by close relatives or friends that the deceased had communicated an intent to commit suicide. Similar acts include giving all his possessions away or repeatedly warning others that he wanted to die.

There are certain modes of death, such as poisoning, drowning and falling from high-rise building, that will give the coroners difficulty in reaching a verdict if no coincidence is found to exist. Under such circumstances, the death would be classified as consequence of "injury undetermined whether accidentally or purposely inflicted" Cases of this type will not be included in the present study. Therefore, all suicide rates presented in this study are based on confirmed cases.

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Suicide rate

The number of deaths from suicide recorded from the calendar year 1981 to 1990 for those under 21 was 225. In addition, there were 68 deaths which were classified as "injury undetermined whether accidentally or purposely inflicted". The annual return of both types for the 1O years is shown in Table 1.

Despite all these limitations of the official statistics, it seems impossible to understand the scope of the problem without referring to the official data. However, the figures have to be interpreted with a degree of caution and an understanding of the source and direction of biases likely to affect the published rates. Shaffer (1974) reviewed coroner's records for all children aged nine to fourteen in United Kingdom, where the catetory of "unnatural death" has applied (undertermined whether death is accidental or purposefully inflicted) and concluded that it seemed likely that most cases of this kind were in fact suicidal in nature. The situation is most probably under-estimated by the official records.

It is noteworthy that the number of undetermined cases had been decreasing throughout the 10 years. For the first five years, 62% of all cases (89 of 144) were confirmed suicide cases. But for the subsequent five years, the proportion was increased up to 92% (136 of 148). Intuitively, investigation made by coroners had become more comprehensive and an undetermined conclusion in an open verdict no longer appeared so frequently.

Suicide rate by year

The suicide rate is defined as the number of suicides per 100,000 in the corresponding age group. As shown in Table 2, there was only a slight increase (20% ) for the 10- 14 age group (from an average rate of 0.5 in 1981-85 to an average rate of 0.6 in 1986-90). But for the 15-19 age group, the rate was increased (from an average rate of 2.31 in 1981-85 to an average rate of 3.81 in 1986-90) by 65%. Although for the whole 10 years, the overall suicide rate of 10-19 was 1.85, the average suicide rate of the 15-19 age group was about 5.5 times that of the 10-14 age group.

It is clearly indicated here that over the past 10 years, there is a 50% increase of suicide among children and youths and most of the increase is caused by those aged between 15 and 19. However, such numerical change may not accurately reflect the real situation as it may only be a direct consequence of the decrease in number of undetermined cases throughout the 10 years. Maybe a restudy of all the undetermined cases can construct a more reliable picture of the issue.

Suicide rate by age

Using the whole population by single year of age in 1986 recorded in the HK 1989 By-census Main Report V. 2 (Census & Statistics Department, HK), the average suicide rates over the 10 years of each age is shown in Table 3. The average rates over 1981-90 by using either the population found in the 1986 by-census (0.55 for 10- 14, 3.19 for 15-19,1.89 for 10-19) as in Table 3 or the population estimation made in each year as in Table 2 as bases are quite similar to each other. Rates based or\ the figures found in the 1986 by-census are thus acceptable approximations. As there is age break-down by single year in the by-census, all types of suicide rates for the rest of this report are based on the population figures reported in that by-census.

Throughout the 10 years, there was only one suicide of age 10. That case was a boy who died in 1990 and he was the youngest one who committed suicide in that period. Suicide under 10 has not been detected in this study. (According to Yap in his Suicide in Hong Kong, published in 1958, there was a girl of six committed suicide in 1954. She was believed to be the youngest case known in Hong Kong.) As indicated in Table 3, there was a sudden increase in suicide rate at age 16. The rate doubled that of the younger age. Similarly, a tremendous increase was also found in age 18. But the rate only increased slightly from age 18 onwards.

Suicide rate by age by sex

In Table 4, the suicide rate by age is further broken down by sex. Just looking at the actual figures, it would easily give one an impression that sex difference existed in different ages as more girls than boys committed suicide in the younger age group, 10-14, and vice versa in the older age group, 15-19. However, the corresponding rates only reflected slight difference and the chi-square value did not indicate a statistical significance.

Comparison with other countries

Despite the observed increasing rate in the past 1O years, suicide among children and adolescents in Hong Kong is, relatively speaking, not as frequent as in many other countries.

As indicated in Table 5, the rates in Hong Kong appeared to be the lowest except that of the younger girls. Girls in Hong Kong aged 10-14 manifested the highest suicide rate among all the selected countries, except Sri Lanka where the rates for any subgroups of teenagers were in fact extraordinarily higher than any one country included. It could also be observed that the Chinese girls of the same age group in Singapore gave similar rate. Further investigation needed to be done to explain the phenomenon.

It is a common finding in most researches that boys outnumber girls as successful suicides by a rather distinctive ratio and attempt rates show major sex difference in the opposite direction. It suggests that successful suicide is a male phenomenon while attempted suicide is a largely female one. However, such differences could only be found in some countries, such as Japan and U.S.A. Rates for Hong Kong, Chinese in Singapore, and Thailand did not demonstrate such a significant sex difference, at least among the teenagers. These findings suggest that the malefemale ratio is most probably determined by cultural rather than fundamental psychopathological factors.

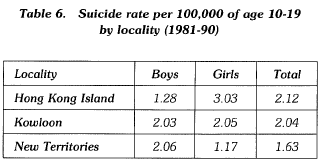

Suicide rate by locality

Due to the lack of information of living population at age 20 in various localities, only cases aged 10-19 inclusively are studied using population estimated by the 1986 bycensus.

From Table 6, suicide rates in the Hong Kong Island and Kowloon district were respectively to be 2.12 and 2.04. But for the New Territories, the rate was as low as 1.63. Such geographic difference was also found in looking at the sex difference. In the Hong Kong Island, the suicide rate for girls (3.03) was about 2.5 times of that for boys (1.28). In the New Territories, the rate for boys (2.06) was about 1.8 times of that for girls (1.17). The rates in the Kowloon district were nearly the same between two sexes. Further looking into the housing type might bring insight into this variation and would be discussed later.

Monthly distribution of suicide

January & February, May & June, and September were peak months for suicides to occur. On the other hand, Nm.;ember was the month that had the least cases.

Several studies on suicide did show a spring or early summer peak, and then an autumn peak. (Dublin and Bunzel, 1933; Dahlgren, 1945; and Sainsbury, 1955). So the second and third peaks in Table 6 were similar to most existing findings in other countries. Stengel (1969) believed that seasonal changes may account in part for the fact that depressive illness were highest in spring and early summer. For most Chinese, January of each year used to associate with many important life events and changes. The preparation of Chinese New Year, school internal examination among students, and the yearly evaluation of personal achievement all come in the same month. These many life changes occurring in such a short period might cause stress and sometimes painful experiences, especially for those lacking social skills or suffering from life failure. This might also account for a surge in suicides in this period of the year.

An interesting finding in the rate of suicide was observed also in the year 1989. Although there were 30 suicides in 1989 which was the second highest in the 10 years, most cases occurred in January and then August onwards There were only three suicides from February to July which was much lower than the average of those six months. Similar discrepancy was not seen in any other years.

One possible explanation might be found in resonating to Durkheim's observations. For most people in Hong Kong, the year 1989 was unforgettable for what happened in the Tien On Mun Square. People looked in the same direction and felt togetherness and possibly at least a temporary meaning to life. The abnormally high suicide rate among the last five months in 1989 might reflect a rebound from the factors operating, and a deepening of the sense of lost, boredom and meaninglessness.

HOUSING TYPE

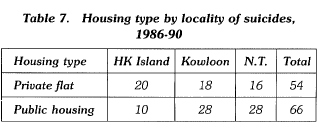

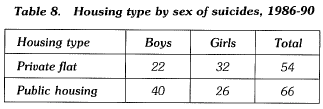

As indicated in Table 7, more cases occurred in public housing estates although residents in public housing estates in Hong Kong only accounted for about 40% of the whole population as indicated in the annual reports of the Housing Department. The analysis of locality by housing type of the suicides reflected that in Hong Kong Island, more suicides were found in private flats but vice versa in bbth

Kowloon and New Territories. The difference is statistically significant (p < 0.03). (According to the Housing Department, the % of population living in public housing estates in different localities were quite constant throughout the period, it is 19% for Hong Kong Island, 47% for Kowloon and 48% for New Territory in.1986.)

Furthermore, there is also statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) in the distribution of housing type by sex of the suicidal. In the private flat, more girls commit suicide, but in the public housing estate, it is the boys that commit suicide more frequently (Table 8). The relatively high suicide rate of girls in the Hong Kong Island as indicated in Table 6 might therefore be related to the low percentage of public housing population in the district.

Two possible hypothesis from sociological considerations might be put forward to explain why more boys than girls living in public housing estates in Hong Kong commit suicide. The first one concerns the personal space available in most public housing units, and the second deals with the parental expectation among the working class in Hong Kong.

The personal space is an area surrounded by an ipvisible boundary line beyond which people expect other to remain. This space stays with us wherever we go, and it sometimes expands or contracts in different situations (Sommer, 1966). It is generally found that very young children maintain little personal space and that the boundaries expand with age (Price and Dabbs, 1974). By age twelve, personal space behavior is like that of adults (Aiello, 1974). There are no sex differences in spacing among very young children, but twelve-year-old boys stand farther apart then twelve-year-old girls. Adult show these same sex differences (Severy, 1979). There are also individual differences in preferred distances. Individuals with a positive selfconcept approach others more closely than do those with a negative self-concept (Stratton, 1973). In addition, violent and nonviolent individuals require differently in their personal space boundaries (Kinzel, 1970). Violent individuals require nearly three times as much area surrounding them as do the nonviolent.

Concerning those who select suicide as a way of release, their self-concepts would appear not to be very positive when viewing the failure and frustration surrounding them. If suicide is also said to be a violent behavior, those who consider this choice will undoubtedly require more personal space in their daily life as suggested by Kinzel's findings. Taking into consideration of sex differences in personal space, it could further be hypothesized that the congested living environment in the public housing estates in Hong Kong might be a factor in pushing depressed boys to commit suicide.

The second possible factor that might have increased the risk of boys living in public housing estates in Hong Kong committing suicide is the unusual high parental expectation on them. Most families on public housing estates are near the bottom of the social ladder, at least when first moving into the units. For most Chinese, it is the boys that are assigned by the parents the duty to improve the socioeconomic status of the whole family. On the other hand, most girls do not experience similar pressure and are only requested to assist in the household chores as directed. (However, most Chinese girls may experience another type of pressure originated for interpersonal relationship, and it will be duscussed later.) Such an identification with the traditional favor of boys seems to occur more frequently among the working class. Consequently, boys are socialized to be more achievement-oriented especially if the parents want to have a better future. They are expected to attain better academic result and experience greater frustration if fail. Therefore, it may be hypothesized that the cultural factor has, to certain extent, caused more boys living in public housing estates to commit suicide.

SUICIDAL ACT

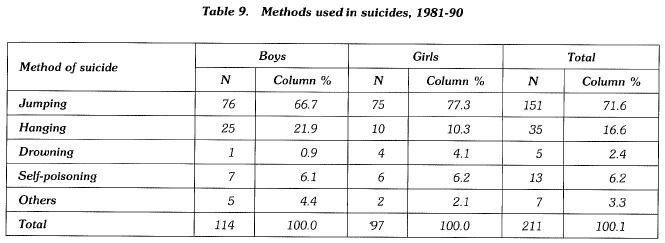

Methods for suicide 211 out of 225 cases had clear records about the methods used in committing suicide. Over 70% selected jumping from a high place to end their lives. The second most popular method was hanging, which seemed to be used more frequently by boys than girls. However, sex difference was not statistically significant (Table 9). Jumping from a high place was a rather decisive action and was employed by both boys and girls with equal frequency in Hong Kong. In fact, in most Western countries, only the boys would use decisive ways, such as shooting, in ending their own lives. Such difference might partly account for the relatively high suicide rate among younger girls in Hong Kong.

They comprised of 72 boys and 64 girls. These 136 cases were analyzed from various dimensions, including housing type, mental health, previous attempt, suicide note, suicidal commmunication, and significant prior incidents.

Previous suicidal attempt

Out of the 136 suicides, 22% of them (30 cases) had records of attempting suicide beforehand. 70% of these 30 cases were girls. 13% of boys and 33% of girls eventually committing suicide had attempted before. These figures correlates well with the general impression that attempt suicide occurs more frequently among girls than boys. In addition, no cases under 16 of either sex had such record.

It was also found that about two-third (19 cases) of these 30 cases were known mental patients. For the male previous attempters, 7 out of 9 were mental patients, but it was only 57% for the female counterpart (12 out of 21).

Suicide note

Suicide notes were found among 34 out of 136 suicide cases. Over 61% were left by boys. 21 (29%) of suicidal boys wrote their last notes but only 13 (20%) of the girls did. Concerning the age, 6 (46%) of the 10-14 age group had written suicide note but for those aged 15-20, 28 (23%) of them had done so similarly. If the leaving of a suicide note were to be an indication of the suicidal determination of the deceased, then most suicides among the younger children were not merely result of their impulsiveness but were behavior which had been undertaken after serious consideration.

Suicidal communication

22 (16%) of all cases were found to have communicated their suicidal intents with others before committing suicide. About two third of them were girls. Only 8 (11%) of the boys but up to 14 (22%) of the girls revealed their intentions to others. As girls were encouraged to reveal their inner feelings throughout their upbringing and were subsequently more expressive in general, their dissatisfaction with life would more easily be detected by other people, and the necessary support and concern could be made available to them before it was too late. On the other hand, the emphasis of keeping one's own feeling among boys in our culture had possibly increased their risk in committing suicide.

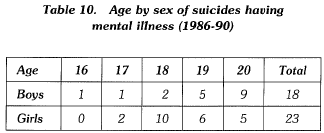

Mental health

There were 41 known mental illness cases out of total 136 from 1986 to 1990. The youngest one was 16 years old but it was the only case of this age. Most mental illness cases were from those aged 17 onwards. Within the 107 cases of age between 17 and 20 inclusive, 37% of them were suffering from mental problems and were active cases of schizophrenia. Onset of mental illness was found to be the main cause for committing suicide among these cases (Table 10). However, as the proportion of suicides among mentally ill adolescent was unknown at the present stage, the prediction power of mental illness in teenage suicide could hardly be defined.

Prior incidents

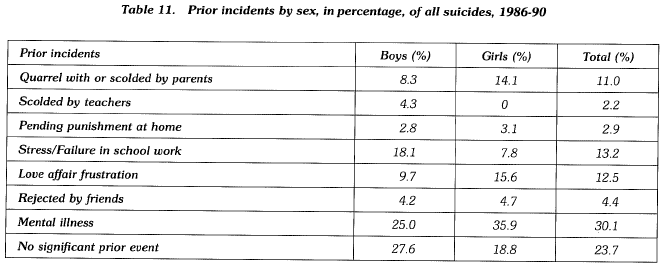

In addition to the onset of mental illness for 41 suicides mentioned before, some prior incidents, which were considered to have direct influences on the subsequent suicidal acts according to coroner's investigation, were found among the remaining 95 cases. The percentages of occurrence among deceaseds of the same sex are shown in Table 11. The figures for mental illness cases are also included for reference. Besides mental illness, there were three types of incidents prior to most suicides, including stress/failure in school work, love affair frustration, and dispute with parents. Sex difference was observed. For boys, stress/failure in school work accounted for 18% of suicides but no one of the other incidents were more than 10%. On the other hand, relationship problems with parents and boy-friends were 14.1% and 15.6% respectively among the suicidal girls and these two percentages were much more higher than those of the other incidents. This difference appears to reflect that the achievement-oriented characteristic of boys and the relationship-oriented characteristic of girls used to generate critical prior incidents in most suicides.

Moreover, only 3 boys, aged 11, 12 and 16, and no girls, committed suicide after being scolded by teachers in school. Although there were 18 suicidal teenagers (equal to 13.2% of all suicides) suffering from the problem of stress/ failure in school work, 16 of them are aged 17 and above. Pressure from study in school appears not to be a signifycant factor for the suicide among younger children. For all the 13 suicides aged 10-14, no one single prior incident was found to account for the majority. All kinds of incidents in Table 11, except love affair frustration and mental illness, were found to have equal weight for this age group. It indicates that for the subjects surveyed, pressure or trouble in school were not a major precipitating factor of suicide among young children.

CONCLUSION

Suicide is an event which unquestionably reverberates in powerful waves through the community in which it occurs. Those closest to the event will feel its effects most. Those closest to the person will be shocked most forcefully. Those who are most unsteady will be at greatest risk for being themselves toppled over. The committed or attempted suicide of a close friend, relative or family member is a destabilizing experience for the adolescent. Those who are particularly vulnerable and without adequate supports or effective means of coping may become dangerously at risk as they collide with the experience of suicide.

In Hong Kong in the past 10 years, there is a gradual decrease in the number of undetermined cases. The suicide rate over the period for those under 21 is found to be 2.2 per 100,000. The rate for the younger adolescents aged between 10 to 14 has only slightly increased by 20%. But for those aged 15-19, it has increased by 65% , from 2.31 in 1981-85 to 3.81 in 1986-90. When compared with other affluent countries such as Japan and the U.S.A., the rate in Hong Kong is extremely low, especially among the boys aged 15-19 because of various cultural and biological factors. Seasonal fluctuation is also observed in local statistics. The result is quite similar to those found in other countries. Empirically, January and February, May and June, and September are hot periods for adolescent suicide.

Concerning the methods used in suicide, jumping from a high place is selected by most teenagers, no matter boys or girls, to end their lives. It accounts for over 70% of all cases. More boys than girls living in the public housing estates commit suicide and such sex difference is most probably caused by the difference in the demand of personal space between the two sexes as well as the traditional expectation putting on boys for achievement in most working class families in Hong Kong.

About 22% of the deceased have records of previous attempts but no cases under 16 has been found to have attempted before. On the other hand, younger adolescents are more likely to leave suicide note. It seems that both the absence of previous attempt as well as the presence of suicide note among the younger adolescents reflect their suicidal behavior to be rather decisive. Furthermore, more girls communicate their suicidal intents with others while most boys keep silent without revealing their intention. Concerning the significant prior incidents in most suicides, onset of mental illness has accounted for over 30% of all cases. In fact, nearly 40% of suicides for those aged between 17 and 20 are closely related to the mental problem of the deceased. Besides, stress/failure in school work is another most common precipitating factor for the boys, but for the girls, it is the relationship problem with either parents or peers.

Finally, it should be noted that the precipitating factor of pressure or trouble in school had only accounted for less than 15% of all cases. its significance is further reduced among suicides of younger children. Such finging is different from what has been perceived by the general public, especially when only the school life of the deceased is re-ported by the mass mdeia in most adolescent suicide cases. In fact, neglecting other factors such as unsatisfactory interpersonal relationship with peers and family members, will prevent our understanding the causes of suicide among children and youths. Certainly, the school should not be the only system that various kinds of effort are made to prevent suicide among adolescents. It should be treated as an entry point to the deteriorating family institution which is the main source of most problems and thus deserves equal and even more attention.

REFERENCES

Aiello, J.K. (1974) The development of personal space in Human Ecolgy.

Census & Statistics Department, HK (1989) Hong Kong 1989 By- census main report vol. 2.

Dahlgren, K.G. (1945) On Suicide & Attempted Suicide, London.

Dublin, L.l., Buuzel, B. (1933) To Be Or Not To Be. New York. Durkheim, E. (1951) Suicide: A Study In Sociology, Glencoe: Free Press.

Gesell, A., Ilg, F.L. (1946) The Child From Five To Ten, New York: Harper & Row.

Glaser, K.(1965) Attempted suicide in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 19.

Gould, R.E. (1965) Suicide problems in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 19.

Headley, L.A. (1983) Suicide in Asia & the Near East. University nf California Press.

Kane, B. (1979) Children's conception of death. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 134.

Kinzel, A.S. (1970) Body-buffer zone in violent prisoners. American Journal of Psychiatry, 127.

Orbach, l. (1988) Children Who Don't Want To Live, California: Jossey-Bass.

Price, G.H., & Dabbs, J.M. (1974) Sex, sitting and personal space. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin.

Sabbath, J.C. (1969) The suicidal adolescent - the expandable child. Journal Of The American Academy Of Child Psychiatry, 38.

Sainsbury, P. (1955) Suicide In London, London.

Severy, L.J. (1979) A multo-method assessment of personal space development in female and male, black and white children. Journal of Non-verbal Behavior, 4.

Shaffer, D. (1974) Suicide in childhood and early adolescence. Journal Of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 15.

Sommer, R. (1966) Man's proximate environment. Journal Of So cial Issues.

Stengel, E. (1969) Suicide & Attempted Suicide, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Stratton, L.O. (1973) Personal space and self-concept Sociometry, 36.

Toolan, J.M. (1962) Suicide and suicidal attempts in children and adolescents, American Journal of Psychiatry, 118.

Yap, P.M. (1958) Suicide in Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press.

Chan Ting Sam B. Soc. Sc., M. Soc. Sc. (Criminology). Parttime Field Instructor, Social Work Department, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin.