J.H.K.C. Psych. (1994) 4, SP2, 13-16

ORIGINAL PAPER

JOINT GERIATRIC-PSYCHOGERIATRIC COGNITIVE CLINIC IN HONG KONG --- A REVIEW OF THE FIRST 31 CASES

Edwin C.S. Yu, David Dai, Derek S.Y. Li, C.S. Au, W.S. Chung

SUMMARY

The first cognitive clinic in Hong Kong was started in May 1993. This paper described the characteristics of the first 31 clients and the interventions by the clinic. The diagnosis is based on DSM III R. More female than male attended the clinic (1.6:1) and the female were older in age (80:76.3). Many of the clients came from old age homes in Sai Kung area but 20% were either referred by the relatives or self referred. Poor memory was the major presenting symptom in the clinic. 26% of the patients were diagnosed to be suffering from dementia and Alzheimer’s disease was the predominant disease among the demented patients seen. 29% of patients were either diagnosed as borderline dementia or benign senescent foget-fulness. Another important group included affective disorder (29%). Many patients had co-morbid conditions. Satisfaction with the services was highly re-garded by carers despite the lack of clinical improvement in many frail elderly.

Keywords: cognitive clinic, Haven of Hope Hospital, multidisciplinary assessment

INTRODUCTION

Cognitive Dysfunction and Alzheimer's Disease are conditions of major significance in the elderly of industrially advanced countries. Hong Kong is beginning to face a similar problem by virtue of her graying population. While 9% of our population is at present aged 65 and above, 11.5% will be expected at 2001 (Census and Statistics Department).

Although earlier reports indicated Alzheimer's Disease and dementia were relatively uncommon in the Chinese, reliable epidemiological database constructed upon a binational survey in Shanghai in 1989 established rates of cognitive impairment in 65 years and above to be 6.9% for severe cases and 19.9% for mild cases. The Chinese female rate for cognitive impairment was about 3 times as high as those reported in the Yale-New Haven study for the same age group (Liu et al, 1993).

Medical clinics specifically for dementia have existed in the United States of America, United Kingdom and Australia. The objects of these memory clinics are four-fold (Fraser , 1992):

- To forestall deterioration in dementia by means of early diagnosis and

- To identify and treat any disorders other than dementia which might be causing memory

- To evaluate new therapeutic agents in the treat- ment of early

- To reassure those who are worried that they are losing their memory, when in fact no morbid deficits are found; and to provide carer support.

Since May, 1993 and for the first time in Hong Kong, a cognitive clinic has been operating at Haven of Hope Hospital, collaboratively by the Kwai Chung Psycho-geriatric Team and the Geriatric Assessment and Rehab-ilitation Unit of Haven of Hope Hospital(HOHH).

This paper describes: the operation of such a clinic in Hong Kong, the demography and clinical characteristics of the first 31 clients assessed from May 1993 to March, 1994, the interventions provided by the clinic and discussion on some findings on the clients.

OPERATION OF THE CLINIC

The clinic is operated once per month, on the first Thursday of each month. The clinic starts with a client interview and examination by the geriatric team with a geriatrician and a geriatric nurse at HOHH at 9:00 am. Attention is paid to comorbid physical illnesses and review of medications, and soliciting a brief account of the cognitive complaint. The Kwai Chung Psychogeriatric Team arrives at HOHH at 10:00 am. The clinical condition of the cases are discussed between the two teams. The psychogeriatrician then performs a detailed psychiatric assessment and ascertain further clinical and psychosocial information from the accompanying carer. Instruments for cognitive assessment in the clinic include the Mini-Mental State Examination and Silver's test. At the end of the assessment, a consensus diagnosis on the mental (according to DSM IDR) and physical condition is made and a joint management plan is formulated.

The management plan can include any of the following form: Routine laboratory and radiological investigations included CBP, ESR, RFF, LFF, T4, sugar, Ca/P and Chest X-ray. Special investigations such as serum B12, folate, EEG, CT scan or MRI of brain, etc. will be arranged if clinically indicated. On-site explanation and counselling would be given to carers, and staff from old age homes. Explanation on medications and other advice on home care were also given. Further home assessment and community support for the benefits of the clients will be organized. Follow-up is usually arranged by the in house geriatric team of HOHH.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

DEMOGRAPHY

More female attended the clinic than male (19:12). The 19 females had a mean age of 80 years(range= 63-93) with 13 widowed, 4 married and 2 single. The 12 males had a mean age of 76.3 years (range= 65-83) with 5 widowed, 5 married and 2 single.

REFERRAL SOURCE

Most of the patients were referred from old age homes (22). We also had some referrals from home helpers (3) and relatives or self referral (6).

PRESENTING SYMPTOMS

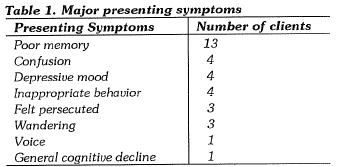

The interval between detection of symptoms by carers to assessment was 10.4 months (range= 1-48 months). 1 client had symptoms for 10 years and 2 clients had previous psychiatric assessment. A client may have more than one presenting symptoms. Major presenting symptoms were tabulated in Table 1.

PSYCHIATRIC DIAGNOSES

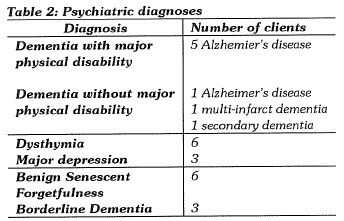

The psychiatric diagnoses noted in the clinic is as shown in Table 2. 1 client had depression and dementia and was counted twice. Other psychiatric diagnoses noted in the clinic included 1 acute confusional state, 1 delusional disorder, 1alcoholic hallucinosis, 1alcohol dependent syndrome and 2 behavioural disorder.

8 of our 31 clients were diagnosed to have dementia according to DSM IIIR criteria. 75% of these cases were considered likely Alzheimer's disease which concurred with generally accepted proportion among all demented conditions.

9 of the 31 patients had a depressive disorder, among which 33.3% were considered suffering from major 9 of the 31 patients were considered not yet demented and not clinically depressed. They were somewhat forgetful, without associated impairment in judgment, abstract thinking and change in personality. 3 clients might be heralding the onset of a dementing illness.

COMORBID MEDICAL CONDITIONS

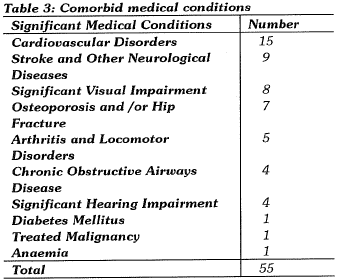

Many of the clients had non-psychiatric diagnoses as well. In average, they had 1.8 non-psychiatric medical conditions. Details were shown over Table 3.

NATURE OF CARERS

Most of the carers in this study were elderly home staff (22). Children (4) and spouse (3) formed a significant proportion of carers for elderly not living in institutions and 2 home helpers became main carers for the elderly patients.

INTERVENTION

The intervention included admission to HOHH for further assessment, drug treatment, counselling for carer/staff of age home, placement in age home, more medical support to clients at age home, financial assistance, reminiscence therapy, follow-up at a psychiatric outpatient department, further home assessment by Geriatric Assess-ment Team, occupational therapy home assessment, advice on alcohol abstinence, management of illnesses of carers and telephone follow up of a sample of the carers.

DISCUSSION

Our clientele at the cognitive clinic belonged to a frail elderly group with a preponderance of female subjects many were widowed. This was related to a longer life, higher prevalence of cognitive dysfunction and higher female sex ratio of aged home inmates which is one of the main target of the clinic. Limited session of the clinic made more widespread advertisement inadvisable.

The introduction of a new service often brings to light deficiencies in existing services (Cammen et al, 1987). Promotion of the service of the cognitive clinic has been brought about by the links with local subvented aged homes through the Sai Kung Geriatric Services Coordinating Committee and the network of contacts by the community nurses. While 71% of all referrals were from local subvented old age homes, only 1.5% of all the clients had previous psychiatric assessment. Although all residential inmates had a preadmission physical check up, cognitive dysfunction might be missed or under-emphasized in the brief assessment. Cognitive decline could also have occurred in some inmates during their subsequent stay in the homes.

The utilization of the cognitive clinic by aged homes allowed us to appreciate the prevalence of cognitive dysfunction in these homes and the concern of age home staff for psychiatric and psychological manifestations of their clients. This confirms the need to provide psychogeriatric support to residential homes and education for home staff in the discernment and management of dementing and other psychiatric illnesses in the elderly. One way to provide a better service in this area might be through a combined psychogeriatric and geriatric assessment team as we have conducted in HOH

Home helper referred cases constituted 9.7% of referrals to the clinic. This group of clients should be considered particularly high 1isk because they were usually physically disabled, dependent on others for self-care activities, and often socially and economically deprived. Given adequate support and back-up, home helpers may form a broad network of "case finders" in the community. 19.3% of clients were directly referred by relatives. However, the cases were initially assessed over the telephone by our Geriatric Liaison Nursing Officer before being offered an appointment. The nursing officer would solicit from the carer a history of memory loss, disorientation, impaired judgment as well as any history of psychiatric illnesses and related symptoms. Clients with features suggestive of dementia or cognitive impairment would be offered an appointment for assessment in the cognitive clinic. This helps to promote the appropriateness of the nature of the conditions to be seen at our clinic.

For conditions like dementia, self reporting of illness by the clients might be delayed or absent with early detection a problem in the absence of any crisis (Williamson et al, 1964). Public education for carers and ready accessibility to a medical service can heighten awareness and proper attitude towards the condition. Thompson held the view that dementia was a latent condition, detectable only by active seeking especially for the early cases (Thompson, 1985).

In our cognitive clinic, memory loss was the commonest presenting complaint. It occurred in 42% of patients. Memory impairment is a salient and early feature of dementia, which can be assessed by history, observation and simple testing (Fraser, 1992).

Literature reminded us that some clients with "benign senescent forgetfulness" on reassessment, at a later stage, may show signs of further cognitive deterioration. Occasionally, a purely subjective sense of cognitive deterioration is sometimes the only indication of incipient dementia (Fraser, 1992). On the other hand some clients labelled as "probable early dementia" were not demented when reassessed some years later (Cammen et al, 1987). A longitudinal follow up of these clients would be worthwhile to assess their progress.

It is important to recognize an acute confusional state secondary to a metabolic, infective disorder or drug effect as a cause of cognitive decline. Our instance was related to congestive heart failure in a client.

In well established cases of dementia, further treatable causes might not be likely. A full battery of investigations in this respect might not be particularly useful. CT scans and EEGs may help in disc1iminating non-demented from mildly demented persons (Brodaty, 1990).

It is also interesting to note the constellation of symptoms arousing concerns to old age home staff and carers. The clinic can, hence, play a role in providing information about the diagnosis of dementia and other psychiatric disorders to carers and assisting them to develop a plan of management. Intervention for the demented in our program still need refinement. More specific memory training programs are waiting for objective evidence of benefit. Fraser (1992). recommended programs which enhance the emotional wellbeing of demented patients and raise the morale of relatives and staff to be genuinely therapeutic.

Australian experience revealed most dementia sufferers were cared for at home and this was preferred by families, sometimes at the expense of high rates of psychological morbidity in the carers (Brodaty & Hadzi-Pavlovic, 1990). A main focus of a psychogeriatric service would include reducing stress in the carers who are usually the spouse, the children, children-in- law. They provide the more intimate and informal support. Formal support may come from the home helper, community nurse and staff of old age homes.

From post-clinic telephone follow up interview of a sample of 5 carers (2 wives, 1 husband, 1 daughter and 1 age home staff), we noted that the major expressed concerns from caring for cognitively impaired persons were: a demanding client, immobility, incontinence, depression, forgetfulness and impaired activities of daily living. Most of these problems persisted or became worse at time of telephone interview of the carers. A betterment was noted in one instance of immobility and incontinence respectively. Hence the clinical condition of the clients were not improved in the majority cases.

Carer stress level can be reflected by self-rated general health, degree of social isolation, use of sedatives, marital/family relationship arid, frequency of visits to a primary doctor ((Brodaty & Hadzi-Pavlovic, 1990). A better status was experienced in 20% of carers. A worse status was reported especially for general health and social isolation. Marital and family relationship have remained stable in 50% of cases and the frequency of G.P. visits was unchanged. All carers had not resorted to sedatives. Satisfaction with the service provided at the cognitive clinic was highly regarded and carers rated on average 9 in a satisfaction scale of 1 to 10.

Brodaty demonstrated the effectiveness of an intensive 10 day residential training program for dementia carers in reducing institutionalization of clients, prolonging survival of clients, reducing carer's psychological distress and improving cost effectiveness (Brodaty & Gresham, 1989; Brodaty & Peters, 1991). A resume for the family carer written in clear simple language could also bridge the communication gap between formal and informal sectors to achieve consistent goals for care at home (Fosteret al, 1987).

The high prevalence of cardiovascular disorders, stroke and neurological conditions, impairment of special senses, osteoporosis and hip fracture described the frailty of our elderly. The Medical/Geriatrics arm of the clinic serve the important role of comprehensive medical assessment and dmg review.

The organization of a cognitive or memory clinic varies in different settings. Cammen et al of UK (1987) described one with input from a psychologist, physician and a psychiatrist. Brodaty of Australia run his academic clinic with a team comprising psychogeriatricians with a neurologist, neuropsychologist, social worker, nurse specialist and occupational therapist.

Our cognitive clinic benefits from the full psychogeriatric team, geriatrician, nurse specialist, social worker, occupational and physiotherapist. Our feature is multi-disciplinary assessment and management.

Cammen et al (1987) reckons a memory clinic of value in the provision of practical clinical assessment, education of the general public and health-care professionals and research in the understanding of the natural history and therapy of dementia. We may add that a cognitive clinic may be a starting point of long term liaison consultation between carer and professional staff, It provides medical support carers including formal carers in the elderly homes in their care of the cognitively impaired clients and facilitated theforming of carer support groups for cognitively impaired clients in Hong Kong.

Dementia presents with multi-facets (Brodaty, 1991) and the focus of attention differs among a clinician, taxonomist and neuropathologist interested in dementing illnesses. However, the impact of illness and burden of health care reside principally on the affected person, family, carer, and the society. The multi-dimensional needs of dementia can be met by no less than a multi-sectorial service structure.

Community outreach, hospital assessment and rehabilitation, long term respite and day care, carer support, planning, advocacy, education and research; working in collaboration, are essential elements of a comprehensive psychogeriatric service (Jolley & Arie, 1992).The working together of a psychogeriatric team and a geriatric team of different hospitals have endeavoured to take a first step towards the establishment of a clinical service network for elderly clients with memory problems.

REFERENCES

Brodaty, H. (1990) Low Diagnostic Yield in a Memory Disorders Clinic. International Psychogeriatrics, 2: 149-159.

Brodaty, H. (1991) The Needs of the Confused Elderly Planning and Design for the Confused Elderly. Conference Proceedings First National Conference, April: 1- 5.

Brodaty H. & Gresham (1989) Effect of a training programme to reduce stress in carers of patients with dementia. British Medical Journal, 299: 1375-1379.

Brodaty, H. & Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. (1990) Psychosocial effects on carers of living with persons with dementia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 24: 351-361.

Brodaty, H. &' Peters, KE. (1991) Cost Effectiveness of a training program for dementia carers. International Psychogeriatrics, 3(1): 11-22.

Cammen,van der, et al. (1987) The Memory Clinic : A new approach to the detection of dementia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150: 359-364.

Census and Statistics Department Hong Kong life Tables, 1986-2011. Census and Statistics Department, HK.

Foster, C., Maitland, N. & Sledmere, C. (1987) Demented patients at home: gaining family acceptance. Geriatric Medicine, Oct: 42-44.

Fraser, M. (1992) Memory clinics and memory training in Recent Advances in Psychogeriatrics, 2: 105-115.

Jolley D. & Arie, T. (1992) Developments in Psychogeriatric Services. Recent Advances in Psychogeriatrics, 2: 117-135.

Liu, W.T. et al. (1993) Health Status, Cognitive Functioning and Dementia among Elderly Community Population in Hong Kong, March, 1993. 1992-93 study report of an Epidemiological Survey of Dementia, Hong Kong Baptist College. p.3.

Thompson, M.K. (1985) Myths about the care of the elderly. Lancet, i: 523.

Williamson J, Stroke, I. H., Gray S.(1964) Old People at home; their unreported needs. Lancet, i: 1117-1120.

*C S Yu, MBBS, MRCPsych, FHKAM(Psych)Consu/tant Psychogeriatrician, Kwai Chung Hospital.

David L.K. Dai MBBS, MRCP(UK), MRCPI, FHKAM Consultant Geriatrician, Haven of Hope Hospital.

Derek S.Y. Li MBBS(NSW), MRCPsych, FHKAM(Psych) Senior Medical Of ficer, Kwai Chung Hospital.

C.S. Au Geriatric Liaison Nursing Of ficer, Haven of Hope Hospital.

Dicky W.S. Chung MBChB, MRCPsych Senior Medical Officer, Kwai Chung Hospital

*Correspondence: Dr. C.S. Yu, Consultant Psychogeriatrician, Kwai Chung Hospital, Kwai Chung, Hong Kong.