Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry (1995) 5, 38-42

Scraps of History: Insane Offenders In Qing

INSANE OFFENDERS IN CHINA

Not much was known for certain on how insane offenders were treated by law in ancient China. Legal historians were also in controversy about whether insane offenders were treated differently from sane offenders.

Karl Bünger (1950) asserted that the exemp on of lunatics from criminal prosecu on was a fundamental notion of ancient China. He cited passages from the ancient Rites of Zhou and Tang Code which indicated clemency with lunatics.

On the other handVan der Valk in 1948 expressed the view (T'oung nα0ser. 238pp 338 - 343) that lunatics had always been held criminally responsible and were accordingly punishedalthough sometimes lighter than sane offenders with reference to one Tang case and several Qing cases of punished insane offenders.

Overall speaking there was apparently a mehonored legal policy of treating the insane with clemency in ancient China. One reason for this was the recognition of insanity as a physiological illness whose etiology and treatment were not fundamentally different from other illnesses since their description in one of the earliest medical treatises such as the Inner Classic of the Yellow Emperor complied between 481 B.C.to 403 c.Even lay Chinese beliefs for insanity such as retribution for sinsloss of one's soul and spirit possession were seen as quite beyond one's control and were potentially curable by physical or spiritual means (maybe with exception for retribution of sins).

During the Zhou periodthe concept of (three pardonables) was developed to ensure lenient treatment of offenders who were very youngvery old or mentally incompetent .An elaboration of this concept was evident in the Tang Code on the basis of which relatively light sentences were handed down to those who suffered from incurle diseases and those who suff ht a t i1ncul ded ins aniyt . No exegesis on insanity can be found in the Tang Code or in any of the subsequent dynastic codes.

INSANE OFFENDERS IN QING

Vivien Ng (1980) studied in depth Qing laws concerning insane offenders and more than 100 cases of insane offenders (mainly killers) culled out from the internal memoranda of the Board of Punishments and other general ci1'culars and various other primary sources and highlighted three themes:

(1) Qing laws concerning the insane particularly those requiring mandatory confinement of all insane personswere an integral part of the imperial push for social control;

(2) laws on insane kille 1's revealed a compromise between pro- and anti-punishment officials;

(3) possible exploitation of the insanity plea by sane 1 urderers was a constant concern.

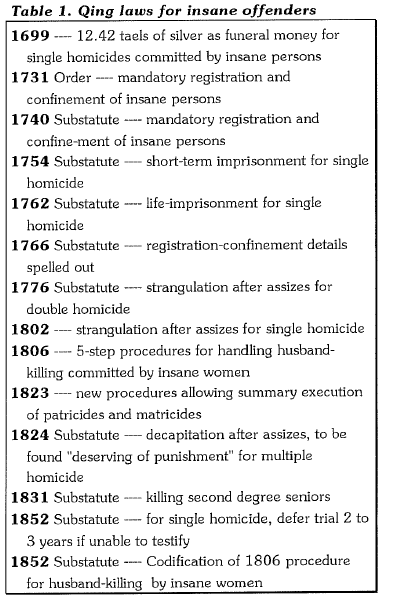

Table 1 shows a chronicle of the additions to Qing laws involving insane offenders. It can be see that the Qing laws and the judicial atlitude towards insane offenders were not static but changed with time. New substatutes were ad hoc additions to the Qing Code pronounced by the Board of Punishments to accommodate emerging legal problems and needs as prompted by legal cases. Laws covering insane offenders were enforced by new substatutes.

There was an obvious trend in the increase in both complexity and severity of sentences rendered to insane offenders. The purpose was more a preven on of fUliher killing rather than punishment.

COMPULSIVE REGISTRATION & CONFINEMENT

Insanity was gradually identified as a "law-and-order" problem by Qing officials who had to deal with acts of violence commitled by the insane and those who pretending to be insane to escape sentenciηg. For example the governor of Shandong submitled a memorial to the Kangxi Emperor in 1689 urging that insane killers should be questioned carefully in order to determine whether they were genuinely ill; if notthey should be sentenced according to the regular statutes for the crimes. Witnesses who gave false testimony about their purported illness should also be punished. He also urged the government to require families of insane persons to watch over them carefully; those who were without families should be made the wards of neighbours and the local agents for social control such as lecturers and local constables .His sugges on was not accepted then.

Prompted by a case of multiple homicide of 4 victims from the same family committed by an insane person the governor-general of Sichllan in 1731 sllbmitted a memorial to the Board of Punishments in which he requested an imperially-sanctioned decree for the mandatory confinement of all insane persons. A order was then issued for families of insane persons to r e.giste r. ht ererm with their migasit t after which the insane persons we re to be coαnifned at hom1 and kept under strict sllrveillance by relatives. The relatives and neighbours magistrates and Banner captains were held accountable for the condllct of the registered insane persons. If the insane person commi tted suicidethe relatives or neighbours would be caned 80 times with a heavy bamboo; the magistrate or Banner captain wOllld lose the eqllivalent of 3 months' salary. If the insane person committed homicidethe pllnishment would be 100 strokes and one year's salary respectively. The recrllitme of the baojia (consolidation of 10 households as a unit) and dibαo (local constabulary) systems whïch were important devices for detection and preven on of crime in registering and confining all the insane persons was equivalent to labelling the insane as "criminal deviants".

The subsequent 1740 registra on-confinement sllbstatute represented the first serious attempt at legislating behaviollral disturbances of lunatics in Chinese legal history. However. this substathlte was not very help3fuω1! because it did not outlined how registration-confinement should be carr d Ollt and how long ht e insane pe rsons should be imlmured.

In 1766, new substatute was formulated to spell out the different procedllres for the confinement of insane men and women. Insane men cOllld be turned over to their families only if the authorities who registered them were satisfied that their families had the facilities to keep them locked up at all times. Insane women were automatically returned to their families after their registratio owing to the Qing policy of not confining female felons unless they had committed a capital offense such as adultery or homicide.

Requisite locks and fetters were isslled by the government to the families. Insane persons who were homeless or whose families were incapable of taking care of them were imprisoned. The exact length of confinement by their own families was not prescribed and they needed to remain conned until their "full recovery". As a family might lie about the recoverythe family had to obtain willing bonds from the clan elderslocal constable and neighbours before submi ing any pe on for release. For those confined in government jailsthey had to remain imprisoned llntil "several years" after their recovery.

These registration-confinement substatutes were difficult to enforce in prac ce because most families did not want to be accollntable for the insane person's conduct and it was so difficult to apply for release once their family members were registered and confin especially if in government prisons.

The famous late-Qing juristXue Yunsheng, commented on this subtatute as "a product of an irrational fearstemming from a few isolated cases of homicide committed by insane persons that all insane persons are potential killers. To pllnish all because of the fault of one is absolutely irrational".

Despite all these criticisms and the diffïculties in pu ing it into practice this registration-confinement substatute was only stricken off from the Qing Code in 1908.

LAWS FOR INSANE KILLERS

During the early decades of Qing dynasty insane offenders were treated very leniently and even killers were set free without trial. However the attitude gradually hardened with concern of possible exploitation of the lenient laws by sane criminals

The subsequent substatutes for insane killers codified clemency towards insane killers as well as a growing prevalence of pro-punishment attitude among officials.

In 1699 the Board of Punishments defined the punishment for single homicide committed by an insane person as a fine of 12.42 taels of silver to the victim's family as "funeral money". This was made a substatute in 1727. This substatute was put into the same discrete group of statutes and substatutes governing (killing during sport or horseplay), (mistaken homicide) and (accidental homicide) although such homicide by insane was not considered as one of these. The fine of 12.42 taels of silver of funeral money was the punishment for accidental homicide. The pu ishment for killing during sport or horseplay and mistaken homicide was strangulation after the assizes. (There were 2 basic kinds of death penalties in Qing. The first kind was death penalty by immediate execution. The second kind was death penalties after the assizes which meant imprisonment until review at the autumnal as es .By then the death penalty would eitlìer be commutated to lighter terms or executed if found deserving of punishment.)

Before 1754, insane killers were simply turned over to the custody of their families after the fine. The 1754 substatute specified that insane killers should be imprisoned until one year after their recovery from insanity. Probably due to the fact that it was difficult if not impossible to determine accurately whether a released inane killer would relapse and kill again life imprisonment was instituted the 1762 substatute for insane killers.

Still unsettled about the possible abuse by sane killers to escape from executionthe Board of Punishments ordered in 1802 that only insane killers already registered and confined before the homicide could be sentenced to life imprisonment. For those who were not previously registeredthey would be given the lighter sentence to strangulation after the assizes if the vic1 's family supported the killers' claim of insanityotherwise decapitation after the assizes if the victirns farnily did not agree. This became a substatute in 1806.

In practice, those unregistered insane killers would probably be commuted to life irnprisonment after the assizes by then further examinatio should have selected out cases feigning rnadness and only those who were obviously and unquestionably insane would be spared.

The enactment of laws spelling out penalties for homicides committed by the insane arnounted to an official recognition of insane killers as crirninals.

MULTIPLE HOMICIDES

Multiple homicide was considered as a very severe offence and the appropriate penalty for sa e killers was irnmediate decapitation. If the victims were from the same familythen the appropriate pe alty would be

(death by slicing) and confiscation of prope . However before 1776 insane killers who had committed rnultiple homicide even with victims frorn same family could only be punished by a fine of funeral money alone or with life imprisonment.

Although the memorial submitled by the judicial comrn sioner of Sian Shi Lijia in 1766 to the Qianlong ernperor proposing for death penalty for insane multiple killers was rejecteda new substatute was enacted in 1776 specifying strangulation aer the assizes for insane killers of double homicide.

The punishment for insane multiple killers was made eve more severe by the 1824 substatute which stipulated either strangulation or decapitation after the assizes (depending on the number of victims and whether they were from the same family) with specification of "deserving of punishment" at the assizes. Hence insane multiple killers had to face almost certain execution after the assizes.

Despite this hardening trendthe punishment was still lighter than death by slicing and confiscation of property for sane killers

OTHER EXCEPTIONS

There were a few other excep ons to the general rule of giving a lighter sentence for insane offenders than sane offenders. These excep ons reflected the govern ment's primary concern on maintaining the social order including the infrafamily hierarchy.

Death by slicing was handed down to all individuals sane or insane found guilty of committing treason patricidernatricide or killing of officials.

Killing of senior relatives was also seen as u pardonable and insane killers were given the sarne punishrnent as sane killers. The substatute in 1831 ensured in effect that insane killers who had killed his second degree relatives would not be treated leniently but would face immediate decapitation.

Owing to the unequal social status between husbands and wivesinsane women killing their husbands were heavily punished by immediate decapitation un 1 a lighter sentence was made possible by a five-step review procedures devised by the Jiaqing emperor in 1802. This was formally made into a substatute in 1852.

PAROLE AND AMNESTY

The 1801 substatute covering the conditions for gran ng parole to insane killers stipulated that a killer who had recovered from insanity could pe on for release from prison to "continue ancestral sacrifices" if he met the following conditions: (1) he was an only son; (2) his parents were old and had no one to care for them; and (3) his recovery from insanity took place while he was in prison.

The second substatute formulated in 1814 extended parole eligibility to those who regained sanity shortly after their arrest with the absolute prerequisite that they had already served five years of their prison terms besides being the only son with aged parents with no one to care for.

These two laws were products of Chinese ideas of filial piety as well as on ancestor veneration and were hence not applicable if the parents had deceased or for wo 1en

For other insane killers who could not benefit from these two laws and female killer they could only wait for their chance of release by general amnesties which were granted to celebrate special days or occasions for the emperor and "clear prisons" / edicts which were almost always issued during times of calamities such as flooddrought or war.

Insane killers were previously excluded from such general.amnesties before 1796. In the 1796 general amnesty commemorating Jiaqing's accession to the throneall insane prisoners who were seventy years or older or those who have served more than twenty years of imprisonment were released.

In 1800 insane prisoners were released for the first time under the clearing of prisons edict with the condition that they had fully recovered from their insanity and had served for at least five years in prison.

Occasionally insane might be released after several commutations of their sentences e.g. to exile provided they had recovered from insanity for more than 5 years.

FITNESS TO PLEAD

A new substatute in 1852 stipulated that killers who remained incoherent after their arrest and unable to testify were to be imprisoned for a period of two to three years. If, during this periodthey regained their sanity they were to be tried and sentenced to strangulation after the assizes - the same sentence for proven insane killers who regained their sanity shortly aer their arrest. In both casesthe death sentence were to be reprieved at the assizes to life imprisonment. As for those who failed to recover their sanity, they would be imprisoned for life without chance of commutation.

ASSESSMENT OF INSANITY

The rationale behind the lenient treatment of insane offenders was the recognition of the fact that these insane persons were not aware of what they were doing. A phrase which appeared in almost every case records involving insane offenders was whïch can be loosely translated as "lacking the capacity to reason or to be aware because of attack of insanity".

Having said that, the judicial officials were left to decide what were the proof of insanity and whether the offender was lacking in the capacity to reason and to be aware at the time of the offence. Possibly physicians were asked in to help in some cases. But from what was noted in the recordsmore often the officials relied on a stereotype of insane behaviours which was shared by both the medical and popular descriptions including: befuddlement, incoherent speech, and senseless mutterings, jumping and dancing in the street, prancing around brandishing knife, and staring blankly and mutely.

The only acceptable ironclad proof of insanity was previous registra on of insanity of the killer to the authorities (which would have resulted in long term confinement at home or in prisons). If not so the officials were expected to spare no effort to determine whether insanity was feigned by the criminals.

Generally speaking any apparent motives such as profitmoney and grudges would be taken as evidence that insanity was not the cause of the homicide. Furthermoreany behaviour sugges ve of any remaining wits such as love of moneycovering up the crime etc. should arouse suspicion.

The officials would have to face the same diffïculty in assessing the recovery from insanity when requesti g for parole or amnesty. On the whole they would rather be over-cautious in giving out lenient sentences to insane killers and in releasing recovered insane offenders as these were already considered as "extra-legal benevolence" in view of the primacy given to social order in Qing China.

REFERENCES

BüngerKarl (1950) The Punishment of lunatics and negligents according to classical Chinese law. Studia Serica, 9 (2): 1 - 16.

Ng, Vivien W. (1980) Homicide and insanity in Qing, China. University Microfilms InternationalLondon.

Researched by T.W. Fan

*The content of this article was abstracted from the dissertation entitled "Homicide and Insanity in Qing China" submitted for Ph. O. in History of the University of Hawaii by Vivien W Ng in Oecember 1980 and published by University Microfils International, London