Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry 2000;10(1):14-18.

REVIEW ARTICLE

SN Chiu

ABSTRACT

Possession is a cultural-bound phenomenon. Due to differences in cultures and individual religious values, people may regard it as a genuine mental disorder or attribute it solely to spiritual disturbance. While psychiatrists are criticised for not understanding religion well, this paper, in an attempt to achieve a holistic understanding of the problem, reviews possession phenomenon in the historical, religious, and medical perspectives.

Keywords: Dissociation; Middle Ages; Possession; Trance

“Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind” — Albert Einstein.1

INTRODUCTION

Possession (or possession-trance) is usually considered to be a cultural-bound phenomenon. It has been reported in Hong Kong,2 Singapore,3 Malaysia,4 India,5 Sri Lanka,6 Japan,7 and Haiti.8 While possession is regarded as a mental disorder in most Western countries, it is often taken as a form of spirit- ual disturbance in societies coloured with polytheism and belief in reincarnation and spirits.9 As a result, a possessed individual would consult an indigenous healer and go through religious rituals before seeking medical attention. This situ- ation is not uncommon in Hong Kong and may be a cause of delayed medical intervention.

Post has commented that “few psychiatrists are trained to understand religion, much less treat it sympatheti- cally.”10 So the psychiatrist’s competence, together with his/ her own religious values, will greatly affect the formulation and management of possession phenomenon. This paper attempts to briefly review possession phenomenon from the historical, religious, and medical perspectives, in order to achieve a better understanding of the problem.

Various possession types and definitions have been cited in anthropological and psychiatric literature. Sociologists such as Walker differentiated possession into a ritual type and a peripheral (or non-ritual) type.11 Ritual possession is a tem- porary, generally voluntary and reversible form. It is central to, and approved by society, and exhibited in the context of religious ceremonies. The peripheral type is a longer-lasting and involuntary phenomenon. It is ‘pathological’ in nature and an evil spirit is the haunting supernatural agent. In this paper, possession refers mainly to the peripheral type, except in the discussion on glossolalia. Furthermore, the religion discussed here is limited to the Protestant and Catholic Churches’ points of view.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Archaeological and anthropological evidence indicates that as early as the Stone Age, man could have a demon-ridden cosmos and a sorcerous treatment of madness.12 In different civilisations across the world, mental illnesses were often thought to be due to different types of possession. Priests and shamans were expected to give expert management of possession by enabling the individual to make sense of the experience and helping the family to manage the victim. Interestingly, priests and physicians were often the same person who played a dual function.13 Such a priest-physician dual role reached its climax when the power of the Catholic Church was at its height. The Church became a centre of religion and knowledge and monopolised medical ideas for a long period of time. It was not until the fifteenth century that medicine and the priesthood went separate ways.

MIDDLE AGES

Possession was widely described in the Middle Ages. Phe- nomenologically speaking, it was poorly differentiated from epilepsy and lunacy, although aetiologically, they came from different sources. At that time, mental illness was considered to be a result of sin.14 A sinner would be subjected to the destructive power of the devil, who in turn was responsible for the afflictions of the mind.15 Epilepsy, however, was not sin-related, but was regarded as a ‘sacred disease’, that is, a

‘gift of Gods’. In the Middle Ages, the task of differentiating a mad man from a possessed person fell into the hands of a medical theologian, lawyer, or physician. The judgement was largely subjective, yet several striking characteristics of a possessed person can be found in historical documents and have been summarised by Oesterreich in his classical writing, Possession: Demoniacal and Other: “… his voice is changed, usually deepens and powerful, body movement is distorted, and the individual would take up a new personality which is frequently scatological or blasphemous. The possession episode is often succeeded by amnesia .…”16

Major changes occurred in the late Middle Ages. During the time of Constantine of Africa (AD 1020-1087), a num- ber of Arabic medical texts were translated into Latin.17 At that time, the Arabs had produced fairly coherent physio- logical models of mental disorders, particularly melancholia. The medieval Church also started to assimilate a physio- logical explanation for epilepsy: “The devil does not cause epileptic attack by his own power. He exerts the influence when the body is off balance, the humors stirred up and the brain affected.”18

EARLY MODERN EUROPE

In early modern Europe, the view on possession was signifi- cantly influenced by the upsurge in the number of witchcraft trials. A possessed individual was regarded as being be- witched rather than spontaneously demon-possessed. As a result, the possessed individual was seen as a victim and was judged innocent. Instead, the identified witch was considered to be a demon in disguise. The ability of the witch to carry out impossible acts such as flying through the air and causing various disasters, along with the ability to withstand torture without pain were proof of possession of demonic power. The suspected witch was often burnt to death after a witch- craft trial. Therefore, the ‘witchcraft mania’ in early modern Europe, apart from eliciting sympathy for the possessed, added nothing to the scientific understanding of possession.

The development of pathology and the discovery of bac- teria were the cornerstones leading to the ‘scientification’ of medicine. Psychiatry, however, was left out of mainstream medicine until the twentieth century. We must thank Karl Jaspers, Emil Kraepelin, and others for establishing a firm basis for descriptive psychopathology and classification. Built on this careful descriptive ground, a number of important advances have been made in psychopharmacology, psycho- therapy, and the understanding of mental illness within the neurophysiological and neuroanatomical context.

In conclusion, there is a slow but general trend of reluctance to attribute possession during the Middle Ages to mental disorder.19 The obsession with witchcraft in early modern Europe engendered the slow pace for accepting a medical model of possession phenomenon.

RELIGIOUS PERSPECTIVE

DESCRIPTIONS OF POSSESSION

Early descriptions of possession and exorcism can be found in the Old Testament of the Bible in the book of Samuel.20 This vignette illustrates the typical relationship between sin, possession, and exorcism. While Saul was King of Israel, he was tormented by an evil spirit because of his sin. Then he called upon David, a shepherd beloved by God who later be- came Saul’s successor, to drive away the evil spirit by playing the harp in front of the King. More demon possession and exorcism stories are found in the New Testament, especially before Jesus Christ was crucified. Interestingly, although insanity, epilepsy, and possession are commonly seen as a result of sin,21 the Bible has distinct descriptions for each of them. Jesus and his disciples were able to distinguish illness from demon possession. Illness was healed through laying on of hands or anointing with oil,22 the demon-possessed would have the demon cast out.23 There are also stories about possessed persons who suffered from epilepsy, and after the demon was driven out, the epilepsy was cured.24

POSSESSION AND SIN

The relationship between sin, possession, and insanity was far more complicated in medieval times. Kroll and Bachrach, in a systematic review and quantitative analysis of a sample of secular and religious texts, and chronicles from pre- crusade sources, successfully extracted every reference to mental illness.25 Of the 57 episodes of mental illness, there were roughly equal numbers of bouts of madness alone, possession alone, and madness combined with possession. Only about one-sixth of these episodes were attributed directly to sin. Sin was most commonly implicated as the cause of madness or epilepsy combined with possession, while possession alone was attributed to sin in only 1 single case. Madness without possession was rarely attributed to sin. This finding contrasted with Zilboorg’s simple conclusion that all mental illnesses were believed to be a result of sin in the Middle Ages.14 The difference may be due to the different sources studied. While Zilboorg used printed historical materials in his study,14 Kroll and Bachrach referred to manuscripts.25

EXORCISM

During the Modern European Renaissance, there was a great reformation in religion. Protestants, after separation from the Roman Catholic Church, held a different view with respect to the power of exorcism — they believed that every believer who prayed would be granted the power of exorcism by God, while the Roman Catholics believed that Jesus Christ had given such power to his apostles and then to the Church. As a result of the ‘religious competition’, many faked posses- sions were identified. Today the Catholic and Protestant Churches still have divided opinions on the way to identify demon possession. The Catholic Church relies heavily on identifying features such as abnormal physical strength, rejection of sacred things, clairvoyant powers, and ability to speak in a different voice or language, together with the test by ‘Holy Water’ to ascertain a suspected possession. The Protestant Church adopts the simple principle documented in the Bible: “This is how you recognize the Spirit of God: every spirit that acknowledges that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is from God, but every spirit that does not acknowledge Jesus is not from God. This is the spirit of the anti-christ ….”26 So the haunting spirit can be reliably tested for its identity by directly asking it in the name of God. Supporting evidence that one is possessed by a demon has been suggested by Nevius.27 The signs included change of personality with a different set of characteristics, and possession of knowledge and intellectual power not belong- ing to the original person.

POSSESSION AND MENTAL DISORDER

To distinguish demon possession from mental disorder is an interesting and important topic to religious people. Koch stated that, in addition to the criteria used by the Catholic Church, a true possession should also have the following features: internal conflict within an individual, sudden recovery after exorcism, and presence of the ‘transfer phenomenon’ — that is the transfer of the evil spirit from one person to another, or from a human being to an animal.28 Cooper maintained that possession included features which are not characteris- tics of mental disorder.29 These included:

- history of previous involvement with the occult

- resistance to prayer

- tendency to curse or blaspheme

- impaired consciousness so as to cut off spiritual help

- clairvoyant powers

- speaking in a different voice or language.

With the rapid growth of the Charismatic Movement during the past decade, the number of reported possessions and successful exorcisms dramatically increased. It is not surprising to see that despite advances in medical knowledge, there is an increasing tendency, in the religious field, to attribute abnormal experiences to a spiritual cause.

MEDICAL PERSPECTIVE

PSYCHOANALYTIC THEORY

The classical psychoanalytic school does not accept the spiri- tual explanation of the cause of possession phenomenon. Freud gave a psychoanalytic explanation of possession as follows: “Cases of demoniacal possession correspond to the neurosis of the present day …. What are thought to be evil spirits to us are evil wishes, the derivatives of impulses which have been rejected and repressed …. We have abandoned the projection of them into the outer world, attributing their origin instead to the inner life of the patient in whom they manifest themselves.”30

Freud’s psychoanalytic point of view about possession is well demonstrated in his analysis of Christoph Haizman’s case.30 Haizmann was a painter who, following his father’s death, developed melancholia. He started to paint pictures of the Devil featured with male and female sexual characteris- tics. He claimed that in order to terminate his suffering, he had sold his soul to the Devil. After examining Haizmann’s study and his paintings, Freud concluded that the Devil was indeed a father-substitute. Giving up the soul to the Devil was a means whereby Haizmann solved his Oedipus com- plex. The bisexual characteristics of the painted Devil reflected his passive homosexual attachment to his father.

Jung did not address himself to the problem of demon possession.31 He was more interested in studying the phenomenon of glossolalia. Glossolalia is defined as the ability to speak a different language because of divine posses- sion. He stated that glossolalia had nothing to do with divine spirit, instead it is a ‘hypermnesia’ phenomenon — a state of heightened memory of things long consciously forgotten but brought back into mind in a dissociated or trance state. Vivier echoed Jung’s view by saying that “Glossolalia occurs either in mass hysterical reaction associated with religious ceremony or in quiet meditation.”32

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

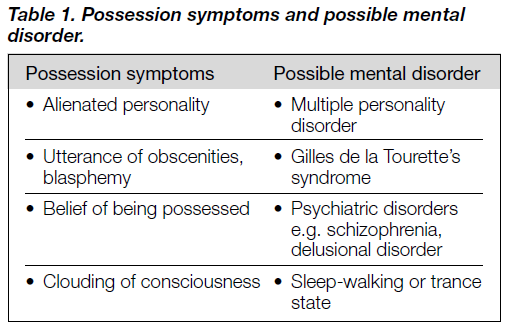

Outside the psychoanalytic arena, possession phenomenon is often akin to hysterical dissociation. For instance, Yap reported a predominance of hysteria (48.5%) in an institu- tionalised Chinese sample (n = 66) presenting with posses- sion phenomenon, followed by schizophrenia (24.3%) and depression (12.2%).2 Although hysterical dissociation is often the diagnosis on referral, different psychiatric disorders have been cited to attempt to explain different possession symptoms. They are summarised in Table 1. Kroll and Bachrach performed a painstaking search of descriptions of visions, voices, and ‘dreams’ in chronicles from the Middle Ages, autobiographies and correspondence between France and England.33 Of the 134 documents analysed, they concluded that about half were descriptions of people in a twilight state and the other half were associated with an organic confusional state as a result of fever, starvation, or terminal illnesses.

It is interesting to note that psychiatric disorder is not always diagnosed among possessed people. In the study by Ee et al., 36 young men presented with possession-trance were followed up for 4 to 5 years, and none of the 26 who could be contacted at the end of the study showed any evidence of psychiatric illness.3

Attempts to explain the adoption of possession phenom- enon (within the context of hysterical dissociation) by an indi- vidual have been made by different authors. It is hypothesised that when a person faces a stressful event that cannot be overcome, he/she will enter a possession-trance in order to solve the conflict. While the person was possessed, the stereo- typical behaviour allows for release of repressed impulses and angry feelings, and the catharsis alleviates anxiety and ten- sion.3 Thus, the occurrence of possession has been reported among people facing various acute stresses such as immigrants from Ethiopia to Israel,34 people anticipating a relationship breakup,4 and new young recruits to the armed forces.35

VULNERABLE FACTORS

Of course, not all people facing unresolved stressful events will enter a possession-trance. One factor that seems to exert a significant aetiological effect is the sociocultural background the person comes from. Possession occurs far more often in primitive tribes or societies with folk belief of spirits and evil. For example, in China, Peng reported that possession phe- nomenon was found more frequently in a rural area (Huaiyin) than in an urban area (Nanjing).36 The difference is account- able from a sociocultural point of view. In India, it was re- ported that 75% of psychiatric patients consulted religious healers about possession.37 Similarly, in a rural community of South Korea, 15 to 25% of psychotic patients were treated by shamanistic therapies.38,39 This reflects the fact that primitive societies are more ready to accept possession as a kind of help-seeking behaviour and spiritual intervention is a common and important alternative to standard medical treatment. Be- ing possessed will allow the individual to seek help in another identity, which is culturally accepted. It also offers strong social bonds and group support within a well-defined subculture.12

Another possible predisposing factor for possession is the individual’s personality. Unfortunately, there are only a few studies investigating this aspect. Ferracuti et al. conducted the Dissociative Disorders Diagnostic Schedule and the Ror- schach Test on 10 people who had undergone exorcisms for demonical possession.40 These researchers found that these people had many traits in common with patients with disso- ciative identity disorder. Furthermore, they were overwhelmed by paranormal experiences. Despite claiming possession by a demon, most patients managed to maintain normal social functioning. The study results should, however, be interpreted with caution because of the limited number of subjects and the subjective element in interpreting the Rorschach Test.

PSYCHOTHERAPEUTIC EFFECTS OF RELIGIOUS RITUALS

Finally, religious rituals may bring about dramatic healing of possession states. For example, in a South Korean rural community, Lee found that for psychotic patients, the sha- manistic approach was effective in 9.7% and other magico- religious folk methods were effective in 44.8% of cases.41 While shamanism or exorcism remains veiled in secrecy in laymen’s eyes, to some psychotherapists, the rapid recovery is accountable in psychotherapeutic terms, namely abreac- tion.42 Abreaction is a kind of cathartic method in which un- discharged and constrained emotion expressed covertly in the form of possession symptoms is released. During exorcism, the religious rituals bring about heightened suggestibility; it is at this stage that the individual’s defence or resistance is broken down easily, and the trapped emotion is set free. It should be emphasised that abreaction can produce adverse effects and should not be practised by unskilled practitioners.

CONCLUSION

This paper has briefly reviewed possession phenomenon from the historical, religious, and medical perspectives. Although there is a growing trend this century to attribute possession phenomenon to mental disorder, controversial opinions remain. Religious authorities such as Wilson may hold an extreme view by saying that “… individuals cannot equivo- cate in their approach to the activities of Satan and his minions … that Christian counselors are the only mental health workers appropriately equipped for this (spiritual) welfare.”43 We, as psychiatrists, should be able to develop a holistic view of paranormal experiences so that we are competent to give professional advice to patients troubled with apparent spiritual issues.

With the growing awareness of possession phenomenon, the World Health Organization has incorporated it into the tenth edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10).44 Possession phenomenon is in the diagnostic category F 44 Dissociative [conversion] Disorders and sub- category F 44.3 Trance and Possession Disorders. Although there is no corresponding diagnostic category in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-IV),45 dissociative trance disorder has been placed in Appendix B: Criteria Sets and Axes Provided for Further Study. Moreover Religious and Spiritual Problem is categorised under V 62.89 when it becomes a focus of attention in clinical practice. McIntyre, the former American Psychiatric Association President, had commented that “the inclusion of the category ‘Religious or Spiritual Problem’ in DSM-IV is a sign of the profession’s growing sensitivity not only to religion but to cultural diversity generally.”46 We sincerely hope that there are more psychiatric researches in this area and spiritual issues are no longer taboo in medical science.

REFERENCES

- Einstein A. Science, philosophy and religion, a symposium. New York: Conference of Science, Philosophy and Religion in their Relation to the Democratic Way of Life, Inc., 1941. http://www.stcloud.msus.edu/~lesikar/einstein/Einstein2b.html.

- Yap PM. The possession syndrome: a comparison of Hong Kong and France findings. J Ment Sci 1960;106:114-137.

- Ee HK, Li PS, Kuan TC. A cross-cultural study of the possession- trance in Singapore. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1986;20:361-364.

- Tai HW, Chin LT. Psychotherapeutic management of a potential spirit medium. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1976;10:125-128.

- Adityanjee MD, Raju GSP, Khandewal SK. Current status of multiple personality disorder in India. Am J Psychiatry 1989;146: 1607-1610.

- Wijesinghe CP, Dissanayake SAW, Mendis N. Possession trance in a semi-urban community in Sri-Lanka. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1976;10:135-139.

- Kuba M. A psychopathological and sociocultural psychiatric study of the possession syndrome. Psychiatr Neurol Jpn 1973;75:169.

- Kiev A. Spirit possession in Haiti. Am J Psychiatry 1961;118:133.

- Varma VK, Bouri M, Wig NN. Multiple personality in India: comparison with hysterical possession state. Am J Psychother 1981;35:113-120.

- Post SG. DSM III-R and religion [letter]. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147: 813.

- Walker SS. Ceremonial spirit possession in Africa and Afro- American. Germany, Leiden: EJ Brill, 1972.

- Ward CA, Beaubrun MH. The psychodynamics of demon possession. J Sci Study Relig 1980;19:201-207.

- Bhugra D. Psychiatry and religion, context consensus and controversies. London and New York: Routledge, 1996.

- Zilboorg G. A History of medical psychology. New York: Norton, 1941.

- Cockerham WC. Sociology of mental disorder. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1981.

- Oesterreich TK. Possession, demoniacal and other. New York: New York University Press, 1921.

- Campbell D. Arabian medicine and its influence on the Middle Ages. London: Kegan Paul, 1926.

- Temkin O. The falling sickness. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University, 1945.

- Kemp S, Williams K. Demonic possession and mental disorder in medieval and early modern Europe. Psychol Med 1987;17: 21-29.

- Samuel 16:14-23. The Bible (NIV).

- Deuteronomy 28:28. The Bible (NIV).

- Mark 6:13. The Bible (NIV).

- Matthew 4:24; 10:8. The Bible (NIV).

- Matthew 17:14-18. The Bible (NIV).

- Kroll J, Bachrach B. Sin and mental illness in the Middle Age. Psychol Med 1984;14:507-514.

- John 4:2-3. The Bible (NIV).

- Nevius JL. Demon possession. Michigan: Kregel Publications, 1968.

- Koch KE. Demonology – past & present. Michigan: Kregel Publi- cations, 1973.

- Cooper A. The Scottish Baptist Magazine 1975; Nov:10.

- Freud S. A neurosis of demoniacal possession in the seventeenth century. The Standard Edition. Collected papers IV. London: Hogarth Press, 1946.

- Jung C. Two essays on analytical psychology. In Jung CG (Ed). Collected works VII. 2nd ed. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1966.

- Vivier LM. The glossolalic and his personality. Bibliotheca Psychiatrica Neurol 1968;134:153-175.

- Kroll J, Bachrach B. Visions and psychopathology in the Middle Ages. J Nerv Ment Dis 1982;190:41-49.

- Witztum E, Grisaru N. The ‘Zar’ possession syndrome among Ethiopian immigrants to Israel. Cult Clin Aspects 1996;69: 207-225.

- Raoul Y, Raoul S. Culte dynastique et possession: le “tromba” de Madagascar. Evolution-Psychiatrique 1982;47:975-984.

- 36. Peng CH. A comparative study of the clinical features of neurosis in urban and rural areas. Chin J Neurol Psychiatry 1990;23(1): 6-8.

- Campion J, Bhugra D. Religious healing in South India. Paper presented at the World Association of Social Psychiatry meeting. Germany, Hamburg; June 1994.

- Kim YS, Cho SC, Kim EY, et al. The attitudes, knowledge and opinions about the mental disorders in the rural Koreans. Neuro- psychiatry 1975;14:365-375.

- Lee CK. Mental disorder in Korea. Neuropsychiatry 1972;11: 187-193.

- Ferracuti S, Sacco R, Lazzari R. Dissociative trance disorder: clinical and research findings in ten persons reporting demon possession and treated by exorcism. J Pers Assess 1996;66: 525-539.

- Lee KH. Study of the Islanders’ concept about the mental illness. Neuropsychiatry 1982;21;375-381.

- Sargant W. The mind possessed. London: Heinemann, 1973.

- Wilson WP. Demon possession and exorcism: a reaction to page. J Psychol Theolog 1989;17:135-139.

- 44. World Health Organization. International classification of 10th ed. Switzerland, Geneva: World Health Organization 1992.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

- Mclntyre J. Psychiatry and religion: a visit to Utah. Psychiatry News 1994;29:7.

Dr SN Chiu, MB, ChB, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM(Psych), Senior Medical Officer, Kwai Chung Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Chiu Siu Ning Kwai Chung Hospital 3-15 Kwai Chung Hospital Road Kwai Chung

Tel: (852) 2959 8111

Fax: (852) 2741 7452

E-mail: snchiupsy@ctimail.com