Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2000;10(3):2-5

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

D Basu, SK Mattoo, H Khurana, S Malhotra, P Kulhara

ABSTRACT

Although risperidone has been hailed as a ‘truly non-cataleptogenic’ antipsychotic and endorsed in standard textbooks as a drug causing minimal or negligible extrapyramidal symptoms at therapeutic doses, our clinical experience with this drug suggests otherwise and prompted this retrospective chart-review of 43 patients receiving risperidone 2- 10 mg/day (both median and modal dose: 6 mg/day) for at least 1 month. While taking a mean dose of 5.77 mg/day, which is well within the therapeutic dose range, 29 patients (67%) developed documented extrapyramidal symptoms, mostly parkinsonism but also akathisia and others. Most patients developed extrapyramidal symptoms in the dose range of 5-7 mg/day (17 of 26, 61.5%), although symptoms were also seen in 9 patients receiving a dose of 2-4 mg/day. That the extrapyramidal symptoms were often clinically significant can be gauged from the fact that 83% of those developing extrapyramidal symptoms required institution of an anticholinergic drug, and 31% required a mean risperidone dose reduction of 2 mg/day. Extrapyramidal symptoms had to be managed by risperidone discontinuation (7% of patients) or a combination of an anticholinergic plus risperidone dose reduction (7%). These observations, though of a retrospective and uncontrolled nature, appear too obvious to be ignored and reflect a need for further study into this issue using a prospective, double-blind, randomised, controlled trial.

Key words: Extrapyramidal Symptoms; Retrospective Study; Risperidone; Side Effects

Introduction

Risperidone, a serotonergic-dopaminergic antagonist, has been hailed as a ‘truly non-cataleptogenic’ antipsychotic,1 meaning that it does not produce extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). The general consensus regarding risperidone is that it certainly causes fewer EPS than other, ‘typical’ neuroleptics and that any EPS seen in the context of therapeutic dose ranges of risperidone are “usually mild”.2 This view has been broadly endorsed by standard textbooks and research literature alike.2-9

In a USA-Canada multicentre project, Marder et al.3 and Marder and Meibach,4 reported EPS with risperidone in daily doses of up to 16 mg to be no more common than in the placebo groups. Cunningham suggested no significant difference in EPS reported by patients receiving doses £ 10 mg from the placebo group.5 Within the recommended therapeutic range (4-8 mg), the incidence and severity of EPS are reported to be much less than 20 mg of haloperidol, even up to 12 months, making risperidone a safer and better tolerated drug than the conventional neuroleptics. Incidence of parkinsonism is reported to be negligible in the therapeutic dose range.6 Indeed, risperidone has also been shown to decrease pre-existing tremors and rigidity.1,7 From these observations one would conclude that risperidone has a safe EPS profile.8,9

Our day-to-day clinical experience with risperidone, however, suggests otherwise. A sizeable proportion of patients with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders taking risperidone began to show EPS that were clinically obvious, often necessitating a halt in further dose increases, reduction of dose, or addition of anticholinergic agents such as trihexyphenidyl. This observation prompted us to review the situation by a chart-review study. Thus, this study had the following objectives:

- To ascertain the proportion of patients receiving risperidone who develop EPS.

- To study the characteristics of EPS and their relation to dose and duration of risperidone therapy.

- To determine the clinical significance of EPS in this group as judged by necessity of risperidone dose reduction and/ or anticholinergic supplementation.

- To examine any differences between those patients taking risperidone who developed EPS and those who did not.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted at the Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India. The Institute is a tertiary-care referral centre in northern India with a large catchment area comprising the north and north-west states of India. The Department of Psychiatry maintains detailed records of patients’ socio- demographic, diagnostic, therapeutic, and follow-up data.

The population comprised all patients from the outpatients and psychiatric ward who were given risperidone between March 1997 and June 1998. The case records were screened retrospectively to collect the specified data. Drug compliance was ensured by corroboration from the records of the nursing staff (for ward patients) or from the accounts of the family members supervising the medication (for outpatients). Only those patients who had completed at least 4 weeks of risperidone therapy were included to allow for a sufficient period for EPS to occur. Sixty seven patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. To avoid contamination of the data, patients with documented EPS before starting risperidone and patients taking EPS-inducing drugs such as antipsychotics, metoclopramide were excluded (n = 24). Thus, the study sample finally comprised 43 patients who had no initial history or evidence of EPS and who were not given any neuroleptics or other EPS-inducing agents prior to starting risperidone.

The following factors were noted: demographic details such as age and sex; clinical details such as duration of illness and International Classification of Diseases-10 diagnosis; and treatment details consisting of peak and maintenance doses of risperidone, duration of risperidone treatment, presence of EPS, type and time of appearance of EPS, dose of risperidone at which EPS was first observed, and details of risperidone dose reduction and anticholinergic supplementation.

RESULTS

The sample consisted of 23 males and 20 females. The mean age was 30.4 years (range 13 to 65 years). Most patients (39, 90.7%) were suffering from schizophrenia; the rest had other psychoses (schizoaffective disorder [2], delusional disorder [2]). Mean duration of illness was 63.6 months.

The maximum daily dose of risperidone given to the pa- tients varied between 2 and 10 mg, with a mean peak dose of 6.26 mg. The daily mean maintenance dose was 5.58 mg, with the dose ranging between 2 and 10 mg (table 1). The median and mode for both the peak and maintenance doses were 6 mg/day. The dosing patterns were according to the standard recommended daily therapeutic dose of 4 to 8 mg.2

Table 3 shows the comparison of the two groups (with EPS vs without EPS). EPS was documented for 9 of 12 patients taking 2-4 mg/day, 17 of 26 patients taking 5-7 mg/day and 3 of 5 patients taking more than 7 mg/day of risperidone.

On comparison, the two groups did not differ significantly in any of the studied demographic and clinical variables (age, sex, diagnosis, duration of illness, peak and maintenance doses of risperidone, and duration of risperidone therapy).

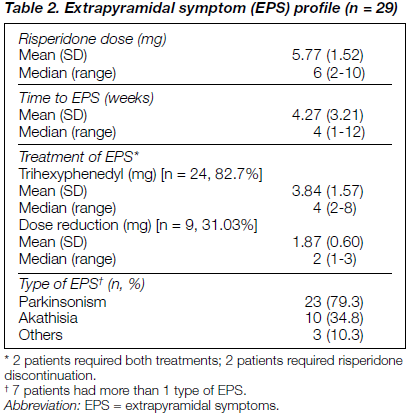

Table 2 shows the profile of EPS in patients while taking risperidone and the management. Of 43 patients, 29 had documented EPS (67.4% of the total sample). Parkinsonism was the most common EPS noted (79.3%). The patients developed EPS within a mean duration of 4.27 weeks at a mean risperidone dose of 5.77 mg/day (median, 6 mg/day). Management of EPS required either risperidone dose reduction (31.03%) or addition of an antiparkinsonian drug (82.7%). For 7% of patients developing EPS, risperidone had to be discontinued. Nine patients required dose reduction of risperi- done by a mean of about 2 mg. For 24 patients, trihexyphenidyl in the dose range 2-8 mg with a mean daily dose of 4 mg was given. For 2 patients (7%) both these methods had to be instituted (table 2).

DISCUSSION

It is important to note what this study can confidently tell us, and what it cannot divulge. As with all retrospective chart-reviews, this small sample study was uncontrolled, non- blind, and did not use any specific instrument to measure EPS. Hence, it cannot tell us if risperidone causes more, less or equal EPS as haloperidol or chlorpromazine at equipotent doses. It also cannot tell us which patients are more likely to develop EPS with risperidone, compared with other neuroleptics.

This preliminary study, however, has a clear and bold message. Two-thirds of the patients receiving risperidone developed clear-cut EPS. These patients had been receiving 2-10 mg/day of the drug, with both median and modal doses of 6 mg/day which is well within the therapeutic dose range. Most patients (17) developed EPS within the narrow therapeutic range of 5-7 mg/day. Even more strikingly, 9 of 12 patients receiving a dose as low as 2-4 mg/day developed EPS. That the EPS was clinically significant can be gauged from the fact that 83% of those who developed EPS needed institution of an anticholinergic drug, 31% required a mean risperidone dose reduction of about 2mg/day, 7% merited both dose reduction and anticholinergic supplementation, and 7% with persistent EPS had to have the risperidone withdrawn.

It must be emphasised that these figures are more likely to be underestimates than overestimates. In clinical notes, EPS is likely to be documented only when present to a clinically meaningful extent, reflected in either overt tremors and gait disturbances or in complaints about these by patients or their attendants when the EPS starts causing a functional impediment. Use of a proper scale to measure EPS in a prospective fashion is likely to detect more and earlier cases of EPS. A double-blind comparison between patients taking risperidone and those taking typical neuroleptics would further clarify the issue.

For the purpose of this paper, one can assert that clinically significant EPS was seen in a substantial proportion of patients taking standard doses of risperidone in the sample studied. This contradicts the commonly accepted clinical dictum that “in dosages [of risperidone] below 10 mg daily extra- pyramidal side-effects are usually mild”,2 that with risperi- done “new EPS were not reported”,1 or that 6-10 mg of risperidone “does not seem to provoke parkinsonism”.6 In this regard, it is particularly interesting to note that, contrary to western reports,6 the vast majority of our patients developed parkinsonism rather than akathisia or dystonia (table 2).

It is beyond the scope of the design of this study to investi- gate or comment upon the basis of such a glaring discrepancy. That would require a prospective, longitudinal, randomised, controlled cohort study design. For the time being, only a few tentative observations and speculations can be offered.

First, almost all studies of effects (and side-effects) of risperidone have so far come from Europe9,10 and America.4 Studies from the East reveal a different picture of EPS with risperidone. EPS with risperidone is reported in about 16% of Oriental patients although it is only clinically significant in 3% of patients,11 while the incidence of EPS following risperidone therapy in moderate doses (6-8 mg) ranged from 29% to 57% in two studies from India.12,13 Agarwal et al. had excluded the incidence of mild and clinically non-significant EPS from the analysis.12 Does this suggest that the Indian population is more prone to develop EPS? It is well established that certain side-effects of drugs and other substances are partly under genetic control of the metabolic pathways, different isomers of enzymes for which can show ethnic variation in distribution. Good examples of the above include higher side-effects of isoniazid in the ‘slow acetylators’14 and of alcohol (the ‘Oriental flush’) in ethnic groups of the East.15

Further, it has been observed that ethnic differences between Asians and non-Asians in the pharmacokinetics of psycho- tropic drugs make the Asians more susceptible to side effects of drugs such as tricylic antidepressants,16 although systematic studies in this regard are lacking.17 It is conceivable that similar ethnic or racial differences in genetically-mediated pathways underlie the higher incidence of extrapyramidal side-effects profile of risperidone seen in our study compared with those in the Western literature. As mentioned above, however, this is currently entirely speculative at best.

Second, it is to be noted that risperidone does not possess any intrinsic anticholinergic activity, unlike some other newer atypical antipsychotics such as clozapine and olanzapine.2 Intrinsic anticholinergic activity of a molecule is known to counter its cataleptogenic activity as seen in the case of low- potency antipsychotics, especially thioridazine.

Finally, it is generally observed that knowledge of the side effects of a drug is directly proportional to its duration of everyday clinical use rather than the phase III trials funded by pharmaceutical companies.8 Thus, only very recently is it dawning upon clinicians that “in everyday clinical practice, EPS appear to occur more frequently than expected”.8 For instance, a recent study in which risperidone and haloperidol were compared in patients with first-episode schizophreniform disorders, reported that almost 60% of the patients on a mean dosage of risperidone 6.1 mg/day developed EPS,18 a finding amazingly similar to ours. Another naturalistic survey did not find any significant advantage of risperidone over more established antipsychotic agents regarding EPS.19 Further, the authors found that the mean dose of risperidone associated with EPS was 3.5 mg/day, considerably lower than that suggested by premarketing studies in more select patient groups9 but very much closer to our findings. Yet another recent study has recommended a less rapid upward titration of risperidone in order to minimise EPS and enhance patient retention.20 Thus, these new-wave clinical research findings based on everyday clinical practice in the naturalistic settings assume great importance and relevance.

In conclusion, our observations of a substantial development of EPS in patients from northern India receiving therapeutic doses of risperidone, although of a retrospective and uncon- trolled nature, appear too obvious to be ignored, and they do establish a need to study this issue further with a prospective, double-blind, randomised, controlled research design.

REFERENCES

- Janssen PAJ, Niemegeers CJE, Awouters F, et al. Pharmacology of risperidone (R64 766): a new antipsychotic with serotonin-S2 and dopomine-D2 antagonistic properties. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1988;244:685-693.

- Van Kammen DP, Marder SR. Dopamine receptor antagonists. In: Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ (Editors). Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 6th Ed. Vol 2. Baltimore MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1995:1987-2022.

- Marder SR, Ames D, Wirshing WC, van Putten, T. Schizophrenia: psychopharmacology. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1993;16:567-587.

- Marder SR, Meibach RC. Risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:825-835.

- Cunningham O. Newer vs older antipsychotics. Drugs 1996;51: 910-928.

- Kerwin RW. The new atypical antipsychotic: a lack of extrapy- ramidal side effects and new routes in schizophrenia research. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164:141-148.

- Ayde FJ. Risperidone: a unique antipsychotic. Int Drug Ther News 1994;29:5-12.

- Fleischhacker WW, Hummer M. Drug treatment of schizophrenia in 1990s. Achievements and future possibilities in optimising outcomes. Drugs 1997;52:915-929.

- Moller HJ. Extrapyramidal side effects of neuroleptic medication: focus on risperidone. In: Brunello N, Racagni G, Langer SZ et al. (Editors). Critical issues in the treatment of schizophrenia. Inter- national Academy for Biomedical and Drug Research. Vol 10. Basel: Karger; 1993:142-151.

- Jannssen Research Foundation. Risperidone in the treatment of chronic schizophrenic patients: an international multicentre double- blind parallel-group comparative study versus haloperidol. Clinical Research Report (Ris-Int-2). Beerse: Janssen; 1992.

- Zhang JZ, Hou YZ, Wang XL, Jia HX. Risperidone for the treatment of schizophrenia. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 1998;8(1):30-31.

- Agarwal AK, Bhashyam VSP, Channabasavanna SM, et al. Risperidone in Indian patients with schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry 1998;40(3):247-253.

- Agashe M, Dhawale DM, Cozma G, Mogre V. Risperidone in schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry 1999;41(1):54-59.

- Mandell GL, Sande MA. Antimicrobial agents: drugs used in the chemotherapy of tuberculosis & leprosy. In: Goodman Gilman A, Rall TW, Nies AS, Taylor P (Editors). Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 8th Ed. Vol II. Singapore: Maxwell Macmillan Pergamon Publishing Corporation; 1991: 1146-1164.

- Bosron WF, Lumeng L, Li TK. Genetic polymorphism of enzymes of alcohol metabolism and susceptibility to alcoholic liver diseases. Mol Asp Med 1988;10:147-158.

- Pi EH, Wang AL, Gray CE. Asian/non-Asian transcultural tricylic antidepressant psychopharmacology: a review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1993;17:691-702.

- Kuruvilla K. Society, culture and psychopharmacology (editorial). Indian J Psychiatry 1996;38:55-56.

- Emsley RA, McCreadie R, Livingston M. Risperidone in the treatment of first episode patients with schizophreniform disorder. Poster presented at the 8th European Community Neuro-Psychiatry Congress. Italy, Venice. 1995, 30 Sept - 4 Oct.

- Carter CS, Mulsant BH, Sweet RA, et al. Risperidone in a teaching hospital during its first year after market approval: economic and clinical implications. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995;31:719-725.

- Luchins DJ, Klass D, Hanrahan P, et al. Alteration in the recommended dosing schedule for risperidone. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:365-366.

Debasish Basu, MD, DNB, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Surendra K Mattoo, MD, Additional Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Hitesh Khurana, MD, Senior Resident, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Sameer Malhotra, MD, Senior Resident, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Parmanand Kulhara, MD, FRCPsych, FAMS, Professor & Head, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Address for correspondence: Dr D Basu

Department of Psychiatry

Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research

Chandigarh - 160 012, India. Tel: (91 172) 746 128

Fax: (91 172) 744 401, 745 078

Email: db_sm@satyam.net.in