Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2000;10(3):6-13

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

SN Chiu, TK Poon, SYY Fong, MY Tsoh

ABSTRACT

This paper reports an analysis of the characteristics of the first 354 outreach patients by the community psychiatric team at Kwai Chung Hospital. By categorising patients into 'new patient' and 'known patient' groups, the reasons for delay in intervention are studied. The diagnosis and violent and suicidal acts are correlated with the outcomes of the out- reach service. Based on the findings, there are a number of important implications for future community psychiatric service development.

Key words: Community Psychiatric Team; Delayed Intervention; Outreach; Violence

Introduction

Until the 1990s, Hong Kong mental health services were predominately hospital-based. Community care for mental patients was mainly provided by non-governmental organ- isations. It was not until late 1994 that three community psychiatric teams (CPTs) were established in different regional psychiatric units, as a result of the following factors:

- The tragic violent incident committed by a psychotic patient in 1982, in which six people were killed and 38 others injured. Thirteen of those injured suffered internal organ damage. The casualties included kindergarden children and adults. The incident reflects the insufficient and inefficient community care of patients suffering from psychotic mental illnesses. A 'priority follow-up (PFU) system' was launched in which patients who had committed violent acts or were considered to have a violent disposition were registered. The PFU category was further divided into PFU (target) and PFU (subtarget) groups. Patients in the PFU (subtarget) group were considered to have the highest violence risk. Additional pre- discharge assessment and aftercare services were available for all PFU patients.

- Overseas experience has shown that community care is a more cost-effective method of looking after seriously men- tally ill (SMI) patients.1,2 Serious mental illness is usually taken to mean schizophrenia or severe affective disorder.

- The recognition of development of secondary handicap in long-term institutionalised mental patients.3

The CPT at Kwai Chung Hospital (KCH) was established in October 1994 and adopts a multidisciplinary model of service delivery. The team members include psychiatrists, community psychiatric nurses, medical social workers, occupational therapists, a clinical psychologist, and a physio- therapist. The CPT provides an outreach consultation service to patients' homes and psychiatric settings within the catch- ment area, which includes Shum Shui Po, Kwai Chung, Tsing Yi, Tsuen Wan, Yaumatei, Mongkok, and Tsim Sha Tsui. The population in the catchment area is approximately one million. With the limited manpower and resources available, the following clients are served:

- Age older than 16 years

- Patients with serious mental illness

- Patients requiring PFU

- Patients with a high readmission rate

- Patients who frequently default out-patient follow-up

- Patients who are suspected to be mentally ill but who have never received proper psychiatric assessment and treatment.

This article comprises a review of the first 354 outreach patients for whom home visits have been made by the CPT. The results will shed light on any existing service gaps and provide evidence for future community psychiatric service development in Hong Kong.

METHODS

This is a retrospective and descriptive case note study. 406 patient referrals were received by the psychiatric outreach services from October 1994 to June 1997 of whom 354 were eligible for the study. The remaining 52 patients were excluded because they had refused outreach services and there was no clinical information available.

At the start of the study, we designed a standardised data- base filling form to collect the following data:

- Sociodemographic background

- Source of referral

- Diagnosis

- Whether the patient was already known to the Hospital Authority psychiatric services:

- at the time of onset of mental illness

- the reasons for delayed psychiatric intervention - Whether the patient was in relapse:

- the duration of relapse prior to outreach service treatment

- the characteristics of the relapse

- the number of admissions to a psychiatric hospital in the year prior to outreach service treatment - Occurrence of a violent act

- Occurrence of a suicide attempt

- The intervention offered by the outreach service.

Any incomplete clinical information was considered to be missing data for that particular part of the study.

The diagnoses were based on the criteria in the Inter- national Classification of Diseases,4 and established by a multidisciplinary team led by a consultant psychiatrist. Patients with comorbidity were also included.

Several common factors for delayed intervention were listed in the database filling form for first-onset mentally ill patients. These factors included concern about stigmatism, trial of non- western medical treatment, initial treatment refusal by patients, lack of awareness of the availability of outreach services, lack of a carer, or not being in Hong Kong at the time of first onset. These factors were listed according to our experience of the reasons encountered. The case notes, including the referral notes, were reviewed to search for these factors. This was an open-ended list and other factors found in the case notes could be specified.

The characteristics of patients who relapsed were described by estimating the number of:

- Outpatients who defaulted

- Patients known to be poorly compliant with oral psychiat- ric medication

- Patients still receiving depot medication

- Patients receiving community psychiatric nursing services

- Patients with priority follow-up status

- Patients previously receiving outreach psychiatric services from KCH.

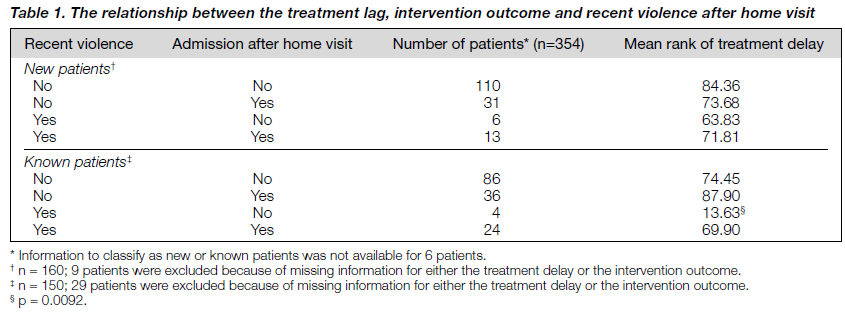

The relationship between the treatment delay, occurrence of violence, and rate of hospital admission was studied for new and known patients using the Mann-Whitney U test. The occurrence of violence was defined in the case notes as a documented violent act. The relationship between the occur- rence of violence and the rate of hospital admissions was examined for both new and known patients. New and known patients were further subdivided into four subgroups, based on

- The presence or absence of recent violence (violent act within the 4 weeks prior to the outreach visit)

- The requirement for inpatient treatment (table 1). Kruskal-Wallis test was then applied.

RESULTS

DEMOGRAPHIC DATA

Sex and Age

One hundred and seventy eight (50.3%) patients were male and 176 (49.7%) were female. The mean age was 45.44 ± 15.96 years (range, 18-86 years) for males and 50.65 ± 18.88 years (range, 20-94 years) for females.

Marital Status and Living Environment

It is often suggested that psychiatric patients are disadvantaged compared with the general population in the two aspects of marital status and living accommodation. Of the 354 patients in the study, 161 (45.5%) were single, 27 (7.6%) were divorced, 43 (12.1%) were widowed, and only 107 (30.2%) were married. The marital status of 16 patients (4.5%) was not indicated in the case notes. Ninety two patients (25.9%) lived alone, while the majority (232 patients, 65.4%) lived with their families. The remaining patients lived in institutions (19 patients, 5.4%) such as a halfway house or long stay care home, or lived with flatmates (10 patients, 2.8%). One patient’s data was missing (0.3%).

Occupational Status

More than half of the patients were unemployed (184 patients, 51.8%); 47 (13.2%) were in full employment, 54 (15.2%) were housewives, 3 (0.8%) were students, and 58 (16.3%) were retired. Occupational information was not recorded for 8 patients (2.3%).

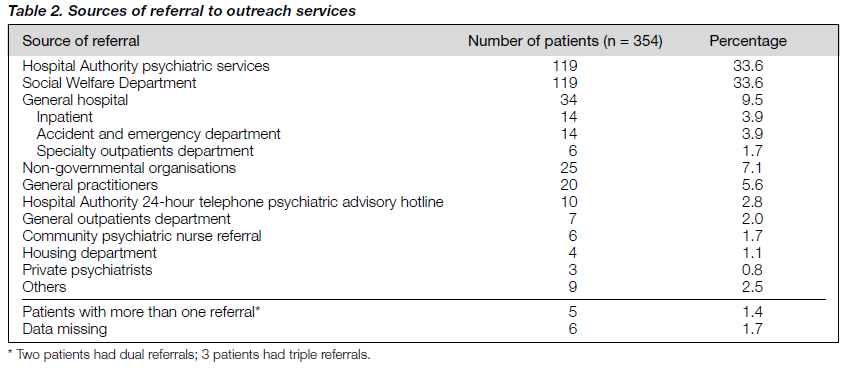

Sources of Referral

The Hospital Authority psychiatric services (including outpatient, inpatient, and consultation liaison services) and the Social Welfare Department were the major sources of referral (table 2). One hundred and nineteen patients (33.6%) were referred from these groups during the study period.

The other major sources of referral were non-governmen- tal organisations, general practitioners, general hospitals (including inpatient, accident and emergency departments, and specialty outpatients departments), and the Hospital Authority 24-hour telephone psychiatric advisory hotline. Five patients were referred from more than one place, while the case notes for six patients (1.7%) did not contain referral data.

Diagnoses

More than 70% of patients had psychotic disorders (table 3). Schizophrenia (203 patients, 57.3%), persistent delusional disorder (51 patients, 14.4%), or other psychotic disorders (7 patients, 2.0%) constituted the majority of the diagnoses. Other major diagnostic groups included dementia (20 patients, 5.6%), depressive episode or recurrent depressive disorder (18 patients, 5.1%), or mental retardation (11 patients, 3.1%). 14 patients (3.9%) had more than one psychiatric diagnosis. The diagnosis remained unclear for five patients.

Violence

Seventy four patients (20.8%) were reported to have a past history of violence — 52 (29.5%) were male and 22 (12.5%) were female. Fifty one patients (34 male and 17 female) experienced recent violence (violent acts within 4 weeks of the home visit), and 33 had a violent act in the previous week. Of the 51 patients, more than 80% were suffering from a psychotic disorder (34 had schizophrenia and 9 had persistent delusional disorder). The other diagnoses associated with recent violence included depressive episodes or recurrent depressive disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, mental retardation, dementia, substance abuse, organic psychosis, or other habit and impulse disorder.

Suicide Attempts

Sixteen patients (4.5%) were reported to have a history of attempted suicide. Only 6 had attempted suicide in the 4 weeks prior to the home visit. Half of them (3 patients) were suffering from a depressive episode or recurrent depressive disorder. The other diagnoses associated with attempted suicide were schizophrenia, persistent delusional disorder, and mental retardation.

In contrast to violence, more female patients (13) than male patients (3) had a past history of attempted suicide. Similarly, five female patients and only one male patient had attempted suicide in the 4 weeks prior to the home visit.

Reasons for Treatment Delay for Patients First Known to Be Ill in Hong Kong

One hundred and sixty nine new patients were first known to be ill in Hong Kong. The duration between the onset of mental illness and intervention for 161 new patients ranged from 1 to 1040 weeks, with a median duration of 104 weeks. There was no data for eight new patients.

The reasons for these 169 new patients not receiving early psychiatric intervention were as follows (more than one reason may be given for one patient):

- Unaware of the availability of the outreach services (88 patients)

- Refusal of treatment by the patient (83 patients)

- Lack of carer for the patient (75 patients); 40 patients were living alone (28 were single, 3 were divorced, and 21 were widowed)

- Concern about the stigma associated with mental illness (11 patients)

- Trial of non-western methods of treatment (10 patients)

- Patients not in Hong Kong at time of onset (2 patients)

- Other (2 patients).

Birchwood et al. reported that the time to the first pre- sentation and treatment after the onset of frank psychotic symptoms averages 1 year.5 In this sample, 111 patients were visited by the CPT during or after the 52nd week from the onset of their mental illness. The median treatment delay for this group of patients was 200 weeks.

Characteristics of Known Patients who Received Outreach Services

One hundred and seventy nine patients were known to be ill in Hong Kong before our visits were scheduled. The duration between relapse and the home visit for 153 patients ranged from 1 to 1404 weeks, with a median duration of 18 weeks. No data were recorded for 26 patients.

Cheung found that one-third of outpatient defaulters in Hong Kong would return to the clinic within 1 to 2 months, even without reminders.6 A known patient who defaulted for 8 weeks or more was considered to have a long treatment delay. There were 104 known patients in this group — the median duration between the relapse and outreach intervention was 51 weeks.

The characteristics of these 179 patients were as follows:

- One hundred and thirty four patients defaulted outpatient visits (median treatment delay of 32 weeks)

- One hundred thirty one patients were known to be poor oral drug compliers

- Fourteen patients were receiving depot treatment; the duration of treatment ranged from 2 to 208 weeks

- Forty one patients were regularly visited by the community psychiatric nurse and 17 had previously been visited by the KCH CPT

- Sixteen patients were PFU targets and one was a PFU subtarget

- Nineteen patients had been admitted to a psychiatric hospital/unit in the previous year.

The duration of admission ranged from 1 to 35 weeks.

Outcome of the Outreach Services

Nineteen patients (6.2%) required crisis intervention, in which the team provided a home visit within 48 hours of receiving the referral. Seven patients were violent and two had attempted suicide during the 4 weeks prior to the home visit. 13 were known patients, with 4 of them being PFU targets.

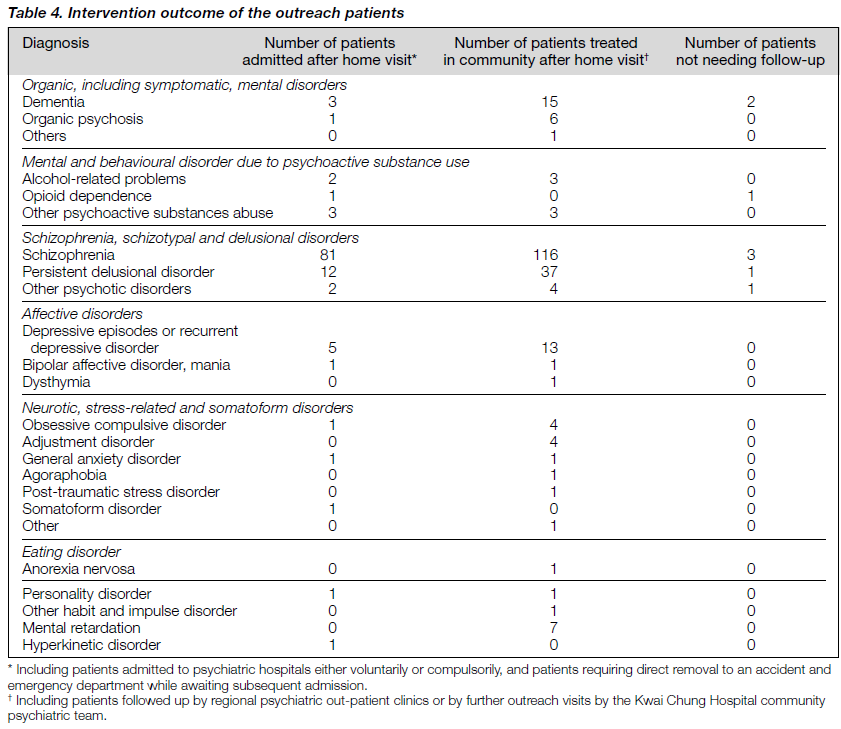

One hundred and twelve patients (31.7%) required admis- sion to hospital. Of these, 75 patients were compulsorily admitted to a psychiatric hospital under Section 31 of the Mental Health Ordinance, 22 went directly to an accident and emergency department because the severity of their symptoms required immediate removal to a place of safety while awaiting subsequent hospital admission, 15 were admitted voluntarily. One hundred and thirty six patients (38.4%) were followed-up at a regional outpatient clinic after the outreach visit. Further outreach visits were required for 81 patients (22.9%). 20 patients (5.6%) did not require further medical intervention. The treatment arrangements were not specified for two patients (0.6%).

Of the patients admitted to hospital, 45 were first known to be ill in Hong Kong and 67 were known to the Hospital Authority psychiatric services. Most of the patients (40 of 51) who were violent in the previous 4 weeks were admitted to hospital, either voluntarily or compulsorily. In contrast, only one of the six patients who attempted suicide was admitted to hospital for treatment, while the others were managed in the community.

Most of the patients requiring inpatient treatment suffered from schizophrenia (81 patients), while persistent delusional disorder (12 patients), or depressive episode or recurrent depressive disorder (5 patients were frequently diagnosed) came next (table 4). For the 217 patients who were managed in the community (either at regional outpatient clinics or by the outreach services), schizophrenia (116 patients) or persistent delusional disorder (37 patients) remained the most common diagnoses. In addition to depressive episode or recurrent depressive disorder (13 patients), dementia (14 patients) and mental retardation (7 patients) were also common diagnoses amongst patients followed up in the community (table 4).

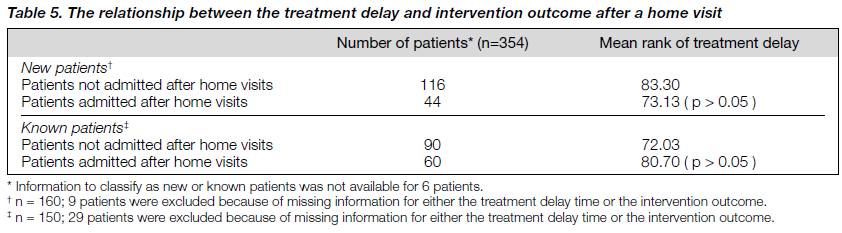

There are always questions about the relationship between treatment delay, occurrence of violence, and rate of hospital admissions for both the new and known patients. The treat- ment delay was not found to be statistically related to the rate of hospital admissions (table 5). On the other hand, recent violence was significantly related to hospital admission (chi-square test, p < 0.0001). New patients and known patients were further subdivided into 4 subgroups based on the presence or absence of recent violent episodes and whether the patients were admitted after a home visit (table 6). Using the Kruskal-Wallis test, no significant differ- ence in the treatment delay time between the four subgroups of new patients was found. However, the treatment delay time was significantly shorter than that of the other subgroups (p = 0.0092) among known patients with recent violent episodes managed as outpatients after the home visits.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study of outreach patients by a CPT in Hong Kong. The CPTs in Hong Kong were established with the objective of serving two groups of clients in the community: suspected mentally ill patients who have never been known or refuse conventional psychiatric intervention and known mentally ill patients who are either frequent defaulters of outpatient treatment or are seriously mentally ill. The latter group is particularly important because some of them are potentially dangerous and most have been repeatedly admitted to hospital. Approximately 70% of outreach clients have psychotic illnesses and this is the most important group for allocation of CPT resources, especially when resources are limited.

The CPT operates with a triage system after receiving a referral. The referral is screened by a senior medical officer to deter mine whether an outreach visit is necessary and the urgency of the case. Patients who appear to be neurotic will be advised to consult an outpatient clinic. Direct contact will be made with the client and the referrer for borderline patients. The initial visit will normally be performed by a doctor and another team member. The visit is usually made within a few days of receipt of the referral. All crises will be followed up within 48 hours. Thus service quality is ensured and resources are effectively utilised.

NEW PATIENTS

Approximately 50% of the clients in this study were first known to be mentally ill in Hong Kong. The median treatment delay of 200 weeks was surprising. Previous studies have shown that intervention early in the course of schizophrenic and psychotic illnesses have critical effects on the long-term prognosis.5,7 Thara et al. found that one-quarter of their sample of schizophrenic patients reached a plateau after the second year of onset.8

Harrison et al. also reported that the course of the illness for the first 2 years after onset was strongly associated with the course over the subsequent 10 years.9 The treatment delay therefore causes the problem of managing a group of relatively difficult-to- treat patients whose prognoses are expected to be poor.

In this study, we tried to find out the reasons for delayed intervention in Hong Kong. The results tell us that more than half of the patients had delayed treatment because they were not aware of the availability of outreach services, or such services simply did not exist at the time their illness started. Thus, there was an undeniable service gap before the CPT was established. Most of these 'suspected mentally ill' clients were treated by family service centre social workers, who often felt helpless because their clients refused to attend a psychiatric unit for proper assessment. Based on these findings, we recommend that, apart from increasing public psycho- education, enhanced publicity of the CPT is needed. In addition, many districts in the region still do not have CPT coverage, and outreach services are desperately needed in these areas.

KNOWN PATIENTS

Delay in intervention was also observed for known patients suffering from relapses (median time delay, 51 weeks). This result reflects that the existing OPD defaulter tracing system is imperfect since 134 of 179 patients had defaulted, although the time delay was a bit shorter at 32 weeks.

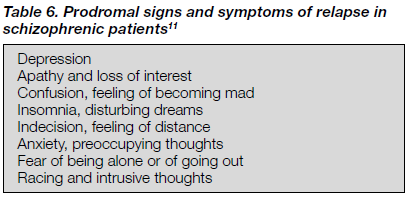

Secondly, carers of mentally ill people should be acquainted with the early signs and symptoms of relapse specific to the patients in their care, so that early detection and intervention are possible. It has recently been shown that schizophrenic patients and their relatives were generally uninformed about recognition of psychotic symptoms and awareness of a need for treatment.10 However, early studies show that prodromal signs and symptoms are often seen in schizophrenic patients before the full-blown relapse occurs.11 These symptoms are non-psychotic in nature (table 6) and both carers and patients should be alerted when these features appear.

Thirdly, we were able to identify a group of known patients who defaulted outpatient appointments, were poorly compliant with medications, had a previous history of violence (or were in the PFU subtarget category), and had had multiple hospital admissions. This group of patients will probably benefit from more intensive mental health service input, for instance case management. Case management has been proved to be successful in engaging patients into the mental health system,12 reducing violence,13 and decreasing the rehospitalisation rate.1,2

Regarding the use of depot medication to enhance relapse prevention, we found that the number of patients who had received depot medication was small. Perhaps those patients who defaulted had no access to such a method of administra- tion before our intervention. This result calls for more optimal use of depot medication as maintenance treatment in relapse prevention and its active implementation through an assertive approach. Another solution to this problem is to establish a weekend depot clinic so that patients who have to work can ensure drug compliance. To this end, KCH opened a Sunday depot clinic in November 1997.

VIOLENCE AND SUICIDE

Our findings on violence echoed previous studies — patients with schizophrenia were most violent14-16 and the violence rate increased with worsening of the patients' mental state.17

It is interesting to note that there is a tendency towards a 'more cautious approach' in managing aggressive patients because about 80% of patients who had shown violent behaviour in the previous 4 weeks were admitted to hospital. On the contrary, patients at risk of suicide apparently can be more easily managed in the community.

There may be social reasons underlying the difference; dur- ing the past few years, violent acts by mental patients have been widely reported by the mass media. Whenever innocent victims were injured, the impact on society was tremendous with the general public expecting clinicians to take every measure to prevent such a tragedy from happening again. On the other hand, suicide is usually regarded by many people as an expected, unpreventable outcome for mentally ill patients.

OUTCOME OF OUTREACH SERVICES

Approximately one-third of our outreach patients required inpatient treatment. 86% were admitted compulsorily, reflect- ing the fact that community care cannot manage without hospital support. Five patients had a psychotic illness but re- ceived no further interventions. After the initial assessment, three clients and their relatives refused any treatment. The remaining two had moved away from the registered address and were unable to be located.

We did not expect that treatment delay would not be related either to occurrence of violence or to the rate of hospital admission. We believe that there is a group of patients whose mental state and behaviour had become so disturbing that they were taken to the casualty before referral to outreach was made, and they were never made known to the CPT. On the other hand, we identified 26 patients who were admitted to a mental hospital through other channels before an outreach visit was made. We hope that with more resources in the future, more patients can receive outreach intervention as soon as possible after we receive the referral.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

Since the case notes were not prepared for research pur- poses they only contained information necessary for deriving a psychiatric diagnosis and subsequent clinical management plan. For a small proportion of referrals, detailed information was not available and these patients were excluded from the study. Additionally, certain clinical information was not actively elicited and recorded during the visit, for example delayed intervention due to concerns about the stigma asso- ciated with mental illness, probably causing under-reporting .

We expected that a small proportion of outreach patients may have their diagnosis modified or changed at a later consultation via admission to hospital or outpatient follow-up after additional clinical information was obtained. This would be particularly likely for those whose first presentation showed inadequate collateral information or was lacking in essential laboratory investigations (toxicology screening). However, we did not perform any tracing to ascertain the consistency of the diagnosis over time.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF A COMMUNITY PSYCHIATRIC SERVICE

This review has a number of immediate implications for community psychiatric services, some of which are already mentioned. One concern raised by these findings is the long median treatment delay for both new and known patients. Those who were severely and persistently ill and resided in the community did not receive the psychiatric services they required. This delay has inevitably prolonged the duration of their suffering and increased the burden for their carers and the community as a whole. This validates the need for community psychiatric services.

A frequently used outcome measure for community psychiatric services is cost-effectiveness, although this does present some challenges. In our community psychiatric team, the multidisciplinary approach is emphasised and the goal of intervention is individually tailored to the needs of the patient. This results in a diverse range and variability of services delivered. Any benefit in terms of clinical outcome is often a result of the various services provided. A simple counting of the number of outreach visits (as we do on a monthly basis) does not truly reflect the service input.

FUTURE RESEARCH

To establish the cost-effectiveness of a community psychiat- ric service, a prospective study of the patient outcomes is needed. Outcome indicators will include clinical ones such as improvement of symptoms, enhancement of drug compliance,

decreased hospitalisation/rehospitalisation rates and length of hospital stay. Social outcome indicators will include quality of life, burden for carers, and patients’ social disability. Other commonly used indicators such as consumer satisfaction and patients' employment level are also areas for future research.

This study focused only on those patients who were living in their own homes. Patients residing at psychiatric in- stitutions such as halfway houses, who have access to our outreach services, should also be subjects for research. One objective of the community psychiatric service is to improve communication and give support to the staff at these insti- tutions. Thus, it is reasonable, after a few years of services, to ascertain the staff view of the CPT services.

Lastly, it will be interesting to compare the outcomes of different CPTs operating in different centres in Hong Kong since each CPT has its own model of service delivery. By doing a comparison study, we would aim to determine which service model is the most cost-effective when applied to the local community.

REFERENCES

- Stein L, Test MA. Alternative to mental hospital treatment I: Conceptual model, treatment program and clinical evaluation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980;37:392-397.

- Hoult J, Reynolds I, Charbonneau-Powis M, et al. Psychiatric hos- pital versus community treatment: the results of a randomized trial. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1983;17:160-167.

- Goffman E. Asylums: essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. New York; Doubleday: 1961.

- The ICD-10 Classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Clinical description and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

- Birchwood M, McGorry P, Jackson H. Early intervention in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1997;170:2-5.

- Cheung HK. A prospective comparison of different ways of trac- ing defaulters in a psychiatric out-patient clinic. Mental Health Association of Hong Kong: Mental Health In Hong Kong. Part III. 1986;88-91.

- Jackson C, Birchwood M. Early intervention in psychosis: oppor- tunities for secondary prevention. Br J Clin Psychol 1996;35:487- 502.

- Thara R, Henrietta M, Joseph A, et al. Ten-year course of schizo- phrenia — the Madras longitudinal study. Acta Psychiatrica Scand 1994;90:329-336.

- Harrison G, Croudace T, Mason P, et al. Predicting the long-term outcome of schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1996;26:697-705.

- Chung KF, Chen EYH, Lam CW, Chen RYL, Chan CKY. How are psychotic symptoms perceived? A comparison between patients, relatives and the general public. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1997;31:756-761.

- Herz MI, Melville C. Relapse in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1980;7:801-805.

- McRae J, Higgins M, Lycan C, Sherman W. What happens to patients after 5 years of intensive case management stops? Hosp Comm Psychiatry 1990;41:175-179.

- Dvoskin JA, Steddman HJ. Using intensive case management to reduce violence by mentally ill persons in the community. Hosp Comm Psychiatry 1994;45:679-684.

- Hafner H, Böker W. Crimes of violence by mentally abnormal offenders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1982.

- Krakowski M, Volavka J, Brizer D. Psychopathy and violence: a review of the literature. Comp Psychiatry 1986;27:131-148.

- Modestin J, Ammann R. Mental disorder and criminality: male schizophrenia. Schizophren Bull 1990;22:69-82.

- Mulvey EP, Lidz CW. Clinical consideration in the prediction of dangerousness in mental patients. Clin Psychol Rev 1984;4:379-401.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Dr KC Yip for his comments on this paper and Miss Elsie Cheung for her clerical work.

Dr SN Chiu, MBChB, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psych), Senior Medical Officer, Kwai Chung Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

Dr TK Poon, MBBS, MRCPsych, Medical Officer, Kwai Chung Hospital, Hong Kong, China. Dr SYY Fong, MBBS, Medical Officer, Kwai Chung Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

Dr MY Tsoh, MBChB, Medical Officer, Kwai Chung Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr SN Chiu

Senior Medical Officer

Kwai Chung Hospital

Lai King Hill Road

Kwai Chung

Hong Kong

China

Tel: (852) 2959 8111

Fax: (852) 2741 7452