Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2001;11(1):17-20

REVIEW ARTICLE

TP Berney

Abstract

The psychiatric services for children and adolescents with learning disabilities in the UK is outlined with discussion on issues relating the extent of the problems, functions of the services (assessment, support, and treatment), and the organisation of services.

Key words: Child health, Child psychiatry, Learning disabilities

Introduction

Services for young people have led the way in developing community approaches that are both multidisciplinary and multi-agency, drawing on a wide variety of bodies including health, education, social services, and the voluntary sector. In the UK, as elsewhere, a well-described network of care has developed in order to minimise the effects of disability and to prevent the emergence of disturbance.1,2 The UK had been unusual in its long tradition of psychiatric services dedicated to people with mental retardation, most of whom were children and adolescents. The development of child psychiatry and a ‘children first’ philosophy, coupled with the philosophy of normalisation, led to the assumption that mainstream child and adolescent services could cater for all their psychiatric needs. At the same time an increase in life expectancy led mental retardation psychiatry to shift its focus to adulthood. In practice, however, although child psychiatry had the requisite developmental approach, it was rooted in a clinic-based, psychodynamic tradition that was largely verbal. It has become clear that young people with disabilities form a distinct group with distinct needs that test mainstream services in several respects:

- the nature of the disturbance is unusual, particularly for those with more severe disabilities where there is a substantial organic component

- the limited communication and comprehension will affect therapeutic style which requires a greater reliance on observable behaviour

- the chronic dependency and disability that distorts family dynamics

- the network of care, which can be so pervasive as to create a subculture that has to be understood and harnessed by the therapist.

The result was that it fell to the growing speciality of community paediatrics to deal with the frequent demands of this small but problematic group. Only recently are we see- ing the evolution of psychiatric services specific to young people with learning disabilities. The debate as to where these should fit into the greater pattern of children’s and disability services is widespread. For example, in North America, while the focus has been on adulthood, some life span services include the whole age range; examples being the Treatment and Education of Autistic and Related Communication Handicap Children programme3 and the Illinois-Chicago Mental Health programme.4

THE EXTENT OF THE PROBLEM

In the UK, 0.2% to 0.7% of the general population have mental retardation sufficient to require specialist health services at some point in their childhood.5-7 Within this group, 40 to 50% will suffer from a significant psychiatric disorder,5,8,9 although this invites the question as to what is ‘psychiatric disorder’. For example, should this term include autism, a disorder for which the main approach is educational? Factors to be taken into account are:

- Autism is a disorder overlapped and mimicked by other conditions such as epilepsy. There is a case for the more intensive investigation of selected cases.10

- It is usually associated with other forms of disturbance ranging from compulsive behaviour through to insomnia and hyperactivity, all of which need treatment in their own right.

- A high public profile brings the risk that autism will become a fashionable, catchall category for any puzzling personality, devaluing it as a diagnosis. It is also an avenue to better resources and families accuse education authorities of restricting the diagnosis to suit their budget. Appraisal has to be independent, expert, and authoritative.

- Fluent salesmen advertise a wide range of expensive treatments, many with a medical rationale. Families need to discuss these with a well-informed professional before dedicating their home or careers to their disabled child.

Such factors mean the psychiatric team has a central role both in establishing the diagnosis and in managing its consequences.

THE FUNCTIONS OF THE SERVICE

ASSESSMENT

The family’s starting point is a diagnosis that it can hold onto, tell others about, and use to cope with a complex set of problems. The vagueness of individualised description or ‘some autistic features’ is unhelpful in a world that responds to problem categories and the unlabelled child finds it difficult to get served. Classification is multi-axial. A specific psychiatric problem is set in the context of a mix of disabilities (it would be a very unusual child who had only an intellectual disability) of differing degrees of severity. These go with medical disorders which may either have caused the disability (e.g. Down’s syndrome) or simply be associated with it (e.g. epilepsy). The problem may stem from family disturbance (or at least be amplified by it) and, in turn, further distort family functioning. The composite diagnosis serves as the basis for a treatment programme.

Assessment goes beyond simply labelling, leading into other services such as genetics, education, and adult provision, with most families wanting a clear mental map of the problems, the services, and the outlook. Diagnosis is too important to be made in isolation and it should be a group effort whether it comes from a team or a more amorphous network.

SUPPORT

This is needed to offset the difficulties of raising somebody with mental retardation. Support includes the routine offer of counselling and help with the development of communication, continence, and domestic routines. Out-of-home placements are also needed, whether for short-term breaks, social emergencies, or long-term residence and, although these should be domestic in character, year-round residential schooling exists and is well used. Too often this provides a face-saving alternative to social care and carries the risk of simply replacing the old-style mental handicap hospital with an equally isolated and institutional school.The prevention of later disturbance is an important element: families have to come to terms with their own feelings about the disability and, in spite of these, to manage their child successfully.11

The level of parenting often has to be well beyond the ‘good- enough’ and has to be tailored to suit the child. Consequently it can be unclear where support ends and treatment begins.

TREATMENT

Services are defined by the disorders they treat (e.g. for epilepsy or autism) or the approach to treatment (e.g. a

‘challenging behaviour’ team) as well as by the population treated. Biological dysfunction and medical disorder, coupled with the maladaptive parenting described above, are much more prominent in the psychiatry of disability than in mainstream child psychiatry.

WHAT KIND OF SERVICE?

The prevailing ethos is that of a ‘children first’ service and leads on to the greater integration of services for young people, ‘childhood’ being ill defined and often including adolescence. This gives yet another boundary for the multi-agency service to grapple with, in addition to those of ability and geography. The problems of ‘coterminosity’ can mean frequent demar- cation disputes, particularly where services are inadequate, and it is essential that there is overlap. This will give the flexibility that allows a service to be tailored to the child’s needs, taking into account other factors such as physical size and personality. The result should be coherent, easy for families both to understand and to navigate through the maze of parallel specialisms. Well coordinated with other agencies and services, the result must be a comprehensive network that covers young people of all ages with all degrees and combinations of disability. The psychiatric service has to be linked to both the following:

- Child health — including child psychiatry, the school health services, the community paediatrician, and the school psychological service as well as hospital paediatrics and the child development team.

- Disability services — particularly the pre-school services, the community team for learning disability, and any specialist behavioural intervention teams as well as parent support groups.

The service must be community focussed, working with the home, school, respite facilities, and community staff. The Health Advisory Service has described mental health services for children and adolescents in terms of a series of tiers making a pyramid.12 All children are in contact with the bottom level, tier 1, which consists of primary workers such as school nurses and general practitioners. Depending on their needs, children are referred up the pyramid and very few will reach the top level, tier 4, which would be a regional or national service. Where there is a specialist service for children with a disability, the same personnel may work at several levels, for example at:

- tier 2 — in outpatient services, most of which will be in the natural environment of school or home

- tier 3 — in specialist teams dealing with areas such as parenting skills, self injury, and the assessment and management of autism

- tier 4 — the inpatient unit.

This range of roles ensures the vertical integration that harnesses all the elements to deliver a coherent service and prevent, for example, the inpatient unit from becoming a remote and expensive irrelevance.

Other links, for example with genetics, neurology, or education, will colour and shape the service. They are encouraged through research, special clinical interest, and junior staff training and protect the service from isolation and stagnancy. The majority of the service is in the community.13

However, some conditions are difficult to manage in the home

— for example:

- Behavioural disturbance at such a level that the family feel unable to cope, e.g. in the presence of severe epilepsy, a grossly disrupted sleep pattern, episodes of violence, or repeated therapeutic failure. Much will depend on the family’s resources and their relationships with each other and their neighbours, as well as their confidence. Effective containment of the behaviour is a frequent starting point for a programme and may be unattainable at home.

- Neuropsychiatric disorders — overactive or disruptive behaviour will preclude admission to many paediatric wards. The assessment of difficult or unusual disturbance needs expert staff; autism, in particular, requires staff who understand its nature.

- Sexual perpetration has become an increasingly frequent element, perhaps because of a greater diagnostic sensitivity coupled with an increasing community awareness and intolerance.

Family disturbance is usual, whether as a cause or effect of the disorder, with a consequent emphasis on family work and the need to be able to admit parents when necessary, for example with a young child or for the assessment of, and training in, parenting skills.

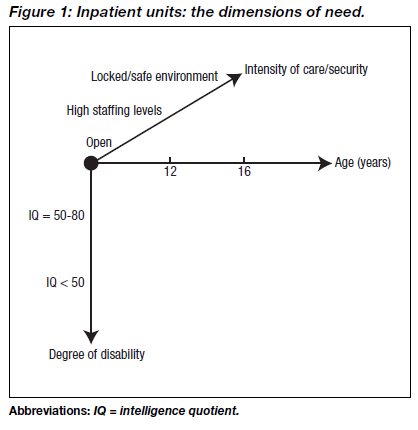

An effective network of care means that there is very little need for admission. Our experience suggests that there should be approximately 1 bed/100,000 general population, although this will depend on what other services and placements are available. These will include a wide range of ages and abilities (Figure 1) and it is difficult for a unit to be effective with a mix of disparate young people. Some form of flexible subdivision, based on demand is necessary, even in a regional (tier 4) resource. However, even though this may be distant from home, a specialist unit remains preferable to an approximation in a paediatric ward, a short break placement, or the longer separation of a residential school. These alternative units frequently find themselves struggling to deal with young people who do not fit into any peer group, are victimised by other patients, and who frequently have an unusual level of violence or activity. The staff find themselves grappling with unfamiliar conditions in which they are uncertain how much is attributable to the background disability.

No unit can function successfully in isolation from the other parts of a service and treatment of a dependent child can only be a temporary success without work with the family and school. The community component is so important that, if it is inadequate, there is little point to admission. The unchanged home either results in relapse or the child remains permanently in the unit turning it into a medium/long term residential placement, which is institutional rather than domestic and too distant from the child’s real home. In particular, the inpatient unit finds it difficult to:

- assess and treat the problems as they arise in their natural setting

- engage closely with parental beliefs and difficulties

- assess any local constraints that might prevent the family and school from maintaining improvement.

One solution may be the specialised outreach service: a team of people who work both in the unit and in the community for a specific child. Where admission to a unit becomes necessary, it is merely an adjunct to the home- or school-based work.14

CONCLUSIONS

This subgroup has become a ‘lost tribe’, falling between specific psychiatric areas and looked after by services whose experience or provisions are inappropriate. Young people have to wait until they reach adulthood to get treatment, a reversal of earlier provision and one that means unnecessary and intractable problems. Matters will only improve when these services are targeted specifically with the explicit involvement of community child heath, learning disability, and child psychiatry. The aim should be to first establish an effective, community-based outpatient service, integrated with the supportive services and, second, access to inpatient resources with an outreach service to bridge the services.

REFERENCES

- Fraser WI. Symposium of the European Association for Mental Health in Mental Retardation: the mental health of Europeans with learning disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res 1993;37(Suppl. 1):1-70.

- McConachie H, Smyth D, Bax M. Services for children with disabilities in European countries. Develop Med Child Neurol 1997;39 (Suppl. 76).

- Schopler E. Implementation of TEACCH philosophy. In: Cohen DJ, Volkmar FR, editors. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1997: 767-795.

- 4. Fletcher RJ. Mental illness-mental retardation in the United States: policy and treatment J Intellect Disabil Res 1993;37 (Suppl. 1):25-33.

- Corbett JA. Psychiatric morbidity and mental retardation. In: James FE, Snaith RP, editors. Psychiatric illness and mental handicap: psychiatric illness in mental handicap. London: Gaskell; 1979.

- Goh S, Holland AJ. A framework for commissioning services for people with learning disabilities. J Public Health Med 1994;16: 279-285.

- Rutter M, Tizard J, Yule W, Graham P, Whitmore K. Research report: Isle of Wight studies 1964-1974. Psychol Med 1976;7: 313-332.

- Einfeld SL, Tonge BJ. Population prevalence of psychopath- ology in children and adolescents with intellectual disability. II. Epidemiological findings. J Intellect Disabil Res 1996;40 (2): 99-109.

- Gillberg C, Persson E, Grufman M, Themner U. Psychiatric disorders in mildly and severely mentally retarded urban children and adolescents: epidemiological aspects. Br J Psychiatry 1986; 149:68-74.

- Gillberg C. Medical work-up in children with autism and Asperger syndrome. Brain Dys 1990;3:249-260.

- Bicknell J. The psychopathology of handicap. Br J Med Psychol 1983;56:167-178.

- Williams R, Richardson G. Together we stand: the commissioning role and management of child and adolescent mental health services. London: HMSO; 1995.

- Lindsey M. Signposts for success in commissioning and providing health services for people with learning disabilities. London: Department of Health; 1998.

- Ward A, Ber ney TP, Dodd S. Riding high. Nurs T imes 1993;89(28):32-34.

Dr TP Berney, MB, ChB, DPM, FRCPsych, FRCPCH, Consultant, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry of Disability, Northgate and Prudhoe NHS Trust, Prudhoe Hospital, Prudhoe, Northumberland, and Fleming Nuffield Child Psychiatry Unit, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK

Address for correspondence: Dr TP Berney

Consultant

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry of Disability

Northgate and Prudhoe NHS Trust

Prudhoe Hospital

Prudhoe

Northumberland

UK