Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2001;11(2):13-18

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

KK Wong, SN Chiu, LP Chiu, SW Tang

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to ascertain the vocational outcomes of individuals with chronic mental illness participating in a supported competitive employment programme. 388 patients enrolled in the programme, which was developed on the basis of the Supported Employment Model and the principles of the Individual Placement and Support. Of the 388 patients, 267 (68.8%) obtained competitive employment. The mean job tenure was 133 days. The mean salary was HK$4,737 for full-time jobs and HK$2,329 for part-time jobs. The majority of the patients (59.6%) sustained their job placement for more than 30 days, 69 patients (25.8%) worked for more than 6 months, and 35 (13.1%) maintained the job for more than 1 year. Patients who became employed were compared with those who did not gain employment on a variety of demographic variables. Significant differences in the source of referral were found between the 2 groups. The rate of employment in this study was slightly higher, but the job retention rate was lower, than in earlier studies. This study concluded that a supported competitive employment programme could be an effective approach to enhancing vocational outcomes for individuals with chronic mental illness. Recommendations for future research for evaluation of the effectiveness of the supported competitive employment programme are suggested.

Key words: Mental illness, Supported employment, Vocational outcomes, Vocational rehabilitation

Introduction

Employment plays an important role in the rehabilitation of individuals with chronic mental illness. According to Scheid and Anderson, work is central to self identity, self esteem, and well being.1 Work may enhance mental health by providing some form of meaningful activity and a sense of accomplish- ment. It is generally agreed that if an individual can work, he/ she is fundamentally well. Since work not only provides direct benefits such as remuneration and social contacts but also promotes gains in related areas such as self esteem and quality of life, much attention has been focused on vocational rehabili- tation services and their ability to produce positive employment outcomes for individuals with chronic mental illness.

To enhance vocational outcomes of individuals with chronic mental illness, a variety of vocational rehabilitation programmes such as vocational assessment and guidance, vocational training, employment services, and sheltered placements have been provided in recent years. However, the results have all been unsatisfactory. It is difficult to find accurate data on the employment rate for individuals with chronic mental illness in Hong Kong. According to statistics from the Labour Department in 1994, the placement rate under the Selective Placement Scheme for individuals with a mental illness was 31%.2

Overseas research has shown that employment rates among individuals with chronic mental illness in the open com- petitive market range from10 to 30%. Only 10 to 15% of those who find work are still employed 1 to 5 years later, and up to 70% of this population remain unemployed.3-6 In a local study conducted by the University of Hong Kong on employment for people with a disability in Hong Kong, 50% of employers did not wish to employ individuals with a mental illness, indicating the difficulty for this population in returning to work.2

Supported employment has emerged in recent years as a viable employment service alternative for individuals with chronic mental illness. It is broadly defined as paid competitive work in an integrated setting with the provision of ongoing individualised support to maintain employment over time. Numerous empirical reports on this approach have been found in the literature, demonstrating enhanced vocational outcomes in the areas of employment rate, job retention rate, job tenure, and earnings for individuals with chronic mental illness.7-11

However, not much is known about the programme outcomes and applicability in the local context. The objective of this study was to ascertain the vocational outcomes of individuals with chronic mental illness participating in a supported competitive employment (SCE) programme. The programme is operated under the Supported Employment Service Committee, Kwai Chung Hospital (KCH). It is designed as a vocational rehabilitation programme to help individuals with chronic mental illness select, obtain, and maintain paid work in an integrated employment setting by means of providing these individuals with the necessary job development skills, placement, training, and support. An individual with chronic mental illness is operationally defined in this study as one whose attending psychiatrist has given a psychiatric diagnosis according to the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Mental Disorders IV,12 and who has had the illness for at least 2 years. Vocational outcomes measured in this study include the rate of competitive employment, job retention rate, job tenure, mean earnings, and type of work placement. The rate of competitive employment is defined as the percentage of referred subjects obtaining a competitive job placement. The placement is further classified into full time and part time work. Job placement with no less than 30 hours of work per week is classified as an full-time placement whereas, for those working for less than 30 hours per week, the placement is classified as a part-time placement. The job retention rate is defined as the percentage of subjects remaining in work during the follow-up period. Job tenure is defined as the total duration (days) of the first job placement under the SCE scheme. Mean earnings are measured as the total wages (in Hong Kong dollars) in the first month of the placement. The type of job placement is broadly defined into 3 categories — clerical, blue collar, and service-oriented — and 2 levels — entry and skilled.

METHODS

PATIENTS

The study comprised 388 patients with chronic mental illness referred to the SCE service from 1 May 1995 to 31 December 1998. The inclusion criteria were age between 16 and 60 years with an interest in competitive employment, absence of a serious medical condition that might affect long-term ability in competitive employment, and valid consent to participate in the study.

SERVICE DESCRIPTION

The SCE programme was developed on the basis of the Supported Employment Model developed by Wehman13 and the principles of the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) Model developed by Becker and Drake.14 The process of job development, on-the-job training, job placement, and support were adopted from Wehman’s model.13 The SCE programme borrowed the concepts of rapid job search, attention to consumer preferences and choice, integration of clinical and vocational services, and continuous and comprehensive assessment from the IPS model.14

Critical elements of the SCE programme include:

- job development — to solicit job placements in employment establishments using various marketing strategies such as cold calls, presentations at employment seminars, and employer interview

- job placement — to prepare and arrange for job entry

- on-the-job training — to apply behavioural strategies to teach job skills on-site and to ensure that job training matches individual learning style

- ongoing support — to provide support services on and off the work site. Operationally, a job coach coordinated the provision of the above services. According to Wehman and Melia, “… a job coach can be a professional or possibly paraprofessional who provides individualised one-to-one assistance to the client in job placement, travel training, skills training at the job site, and ongoing support; the job coach is expected to reduce his or her levels of support over time as the client becomes better adjusted and more independent at the job.”15

The duration of support provided for individuals with chronic mental illness may become a critical variable in determining vocational outcomes. Some evidence suggests that vocational outcomes such as the job retention rate may be maintained or even increased over time if support continues for a long period of time.16-18 To ensure optimal follow-up support for the patients in this study, the qualifications of the job coach and the schedule of the follow-up support have been standardised. All job coaches in this study were registered Occupational Therapists in Hong Kong with at least 1 year of clinical experience in rehabilitation of individuals with psychiatric disabilities.

Follow-up support in the form of job site visits, on-the-job training, and telephone contact was provided at least twice per week for the initial 3 months of the placement. Thereafter, support was provided at least once per month. For those individuals who obtained job placements, support was continuously provided until either the placement was terminated or the individual had been working for 2 years. Individuals were thought to have obtained the maximum benefits from the programme by the end of this period. On the other hand, for those individuals who did not obtain a suitable job placement, job coaching services (mainly development programmes) were provided for 6 months from the date of entry into the programme. To ensure the quality of the job coaching service, each job coach had a maximum caseload of 12 individuals at any one time. Under the SCE programme, employers were routinely informed that the prospective employees had a history of mental illness but were now stable and ready to work. The employers hiring these individuals were given relevant resources and support to cope with workers who suffer from mental illness.

PROCEDURE

Patients referred to the programme were scheduled to meet the job coach to begin the data collection process. The job coach conducted an initial interview to collect demographic information, including personal particulars, and to identify a suitable job placement for the individual based on their educational background, preference, and previous work experience. When a suitable post was identified, the job coach would accompany the patient to the interview at the place of employment.

On the date of commencement of the job, the job coach would accompany the patient and provide on-the-job training if required. Thereafter, the job coach would provide all necessary support for the individual to retain the job. The pattern of ongoing support provided for the patients was more intensive in the initial phase of the placement followed by gradual tapering as the individual became more independent. This pattern was designed to match the course of mental illness, which is episodic in nature. If the subject failed to retain the job, a job termination interview would be conducted within 1 week to investigate the reasons for the failure.

ASSESSMENT TOOLS

Three assessment forms were designed for data entry:

- referral form of the SCE service for demographic data, including age, sex, marital status, education level, and diagnosis

- a job placement and follow-up record was used to assess the job retention rate, job tenure, nature of job placement, and earnings when an individual obtained a job placement

- a job termination form was used evaluate the reasons for the termination of employment.

RESULTS

DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

388 individuals with chronic mental illness were referred to the SCE service, KCH, from May 1995 to December 1998. The majority of the patients (84.8%) were referred from KCH or cluster units (Ngau Tau Kok Psychiatric Clinic, South Kwai Chung Psychiatric Clinic, or Yau Ma Tei Psychiatric Clinic). Fifty nine individuals (15.2%) were referred from other psychiatric units in Hong Kong, including Kowloon Hospital, Lai Chi Kok Hospital, Shatin Hospital, Tai Po Hospital, Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun Polyclinic, United Christian Hospital, Western Psychiatric Centre, Yung Fung Shee Memorial Clinic, and private psychiatrists.

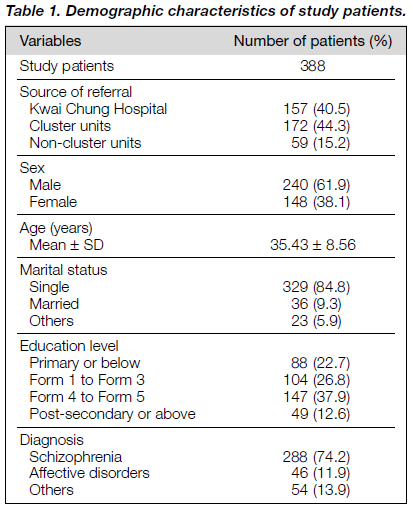

240 patients were male and 148 were female (Table 1). The mean age was 35.4 years old (range, 17 to 60 years). The majority of the patients were single (84.8%), 9.3% were married, and the remaining 5.9%, including divorced, sepa- rated, and widowed, were classified as others. 288 patients were diagnosed as having schizophrenia, while 46 had affective disorders (mania or major depression), and the remaining 54 had non-psychotic diagnoses of alcoholism, anxiety disorder, mental retardation, personality disorder, or obsessive compulsive disorders. The profile of the educational level of the patients is shown in Table 1.

VOCATIONAL OUTCOMES

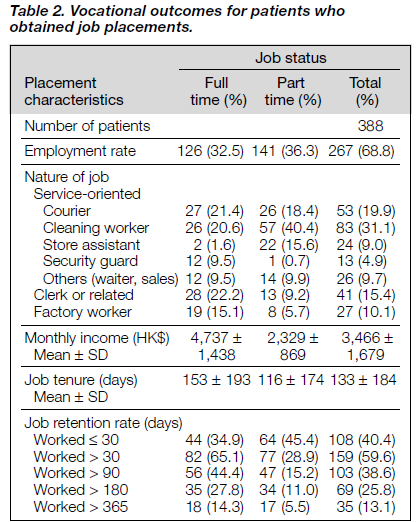

Of the 388 patients, 267 obtained competitive employment with 126 in full-time and 141 in part-time employment, respectively. The average monthly earnings were HK$4,737 for the full time workers and HK$2,330 for the part time employees. The mean job tenure was 133 days.

The majority of the patients (59.6%) sustained their job placement for more than 30 days, 103 (38.6%) maintained employment for more than 3 months, 69 (25.8%) worked for more than 6 months, and 35 (13.1%) sustained the job for more than 1 year (Table 2). However, 108 individuals terminated their job within the first month of placement. There was no demonstrable statistically significant differences in the job tenure between the various demographic groups (sex [t(265) = -0.92; p = 0.356]; marital status [F(2,264) = 1.26; p = 0.285]; diagnosis [F(2,264) = 0.598; p = 0.551]; job status [t(265) = 1.66; p = 0.098]; and education level [F(3,263) = 1.105; p = 0.347]).

With regard to the nature of the work, service-oriented jobs constituted the major job category (199 patients). Service- oriented jobs consisted of courier service, cleaning work, store assistant, and security guard. Twenty seven patients (10.1%) were employed in the manufacturing industry, and the remaining 41 patients (15.4%) were hired for clerical-related posts. Most of the posts were classified as entry-level jobs that required minimal demands on an educational level or previous work experiences. Table 2 shows the vocational outcomes of patients who obtained a job placement.

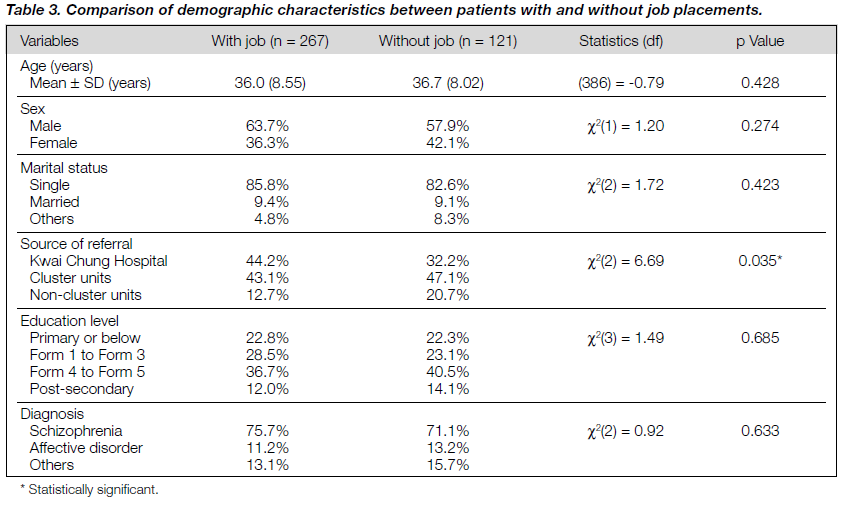

Further analysis was conducted to deter mine any statistically significant differences between the groups who obtained employment and those who did not. The two groups were similar in terms of age, sex, marital status, educational level, and diagnosis. They differed only in the source of referral with a significantly higher percentage of patients referred from KCH obtaining a job. The comparison of demographic characteristics between patients with and without job placements is shown in Table 3.

REASONS FOR JOB TERMINATION

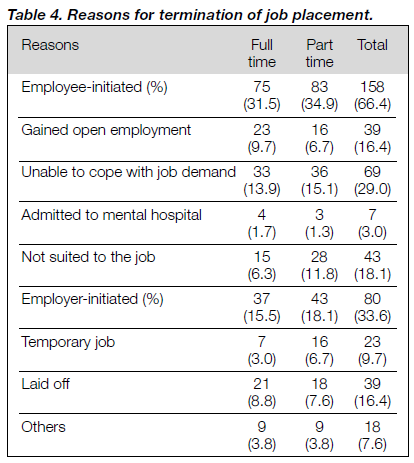

Of the 267 patients with job placements, 19 were still working at the end of 1998, 10 had worked for 2 years, and 238 individ- uals had were stopped work. The reasons for termination of employment fell into 2 categories — employee-initiated and employer-initiated. As shown in Table 4, the employee- initiated termination made up a greater proportion (59.2%). The most frequently cited reasons for termination were “unable to cope with job demand” (28.9%), “having gained open employment” (14.6%), and “not suitable for the job” (16.1%). Only 7 workers (2.6%) were terminated because of admission to hospital. Among the employer-initiated job terminations, the majority of individuals were laid off by the employers (16.4%), 9.7% were due to the temporary nature of the job, and 7.6% were terminated for “other reasons”.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the vocational outcomes of individuals with chr onic mental illness participating in the supported competitive employment programme of Kwai Chung Hospital. The results of the programme were encouraging. 267 individuals (68.8%) obtained a competitive job placement. The majority of the job placements were service-oriented in nature (74.5%), including cleaning work, courier, security guard, and store assistant. Forty one patients (15.4%) found clerical or related jobs and only 27 (10.1%) were employed in the manufacturing industry, which is in line with the change in labour demands in Hong Kong from manufacturing to service-oriented industries.

The mean salaries for the full-time jobs (HK$4,737) were significantly lower than the average income of the general population. This may be attributed to the fact that the majority of these individuals were given entry-level jobs that required no demands for education or previous work experiences. The average job tenure for patients who obtained a job placement was 133 days.

Significant differences in job acquisition and job tenure existed between patients from different referral sources (X2[2] = 6.69; p = 0.035). It appeared that patients from KCH obtained jobs more easily but were more likely to fail. One possible explanation is that patients from KCH are psychiatric inpatients who are ready for discharge and are more inclined to focus on the extrinsic nature of the placement such as salary, location of available posts, and working hours rather than the intrinsic characteristics such as job demand, personal preference, and experience. Patients from other centres tended to show more understanding of the importance of job matching.

Most of the patients who terminated their employment were in the ‘self-initiation’ group. From our understanding of mental health, individuals with chronic mental illness often find difficulty in coping with the demands of a job such as heavy workload and long working hours, especially in the first few days of employment. This may be due to their lengthy period of unemployment, long-term hospitalisation, psychiatric impairment, and maladjustment to the work site. In this regard, intensive follow-up support is critical in the early phase of employment to help individuals with chronic mental illness adjust to their work. In this study, 7 patients terminated their employment because of admission to mental hospital.

This relapse rate is much lower than the natural relapse rate of individuals with chronic mental illness. Two reasons might account for the reduced relapse rate. First, in addition to providing support for work, the job coach also provided support for daily living, family relationships, and engagement in psychiatric follow-up. In this regard, patients participating in the SCE programme would have a better mental state and better drug compliance, which in turn enhances community tenure. Second, work itself may be considered as having a protective effect on both the symptom and relapse rate for individuals with chronic mental illness. Bell et al conducted a study on the clinical benefits of paid work activity for patients with schizophrenia and concluded that paid work increased participation and that participation was primarily responsible for symptom reduction and lower rehospitalisation rates.19

Overseas studies show comparable results on the vocation- al outcome of the programme. Fabian reported that 36% of subjects who participated in a supported employment programme obtained paid employment, 75% maintained the placement for 3 months, and 59% sustained employment for 6 months.20 Shafer and Huang reported that 60% of the supported employment participants found paid jobs.21 Among these individuals, 25% left employment within 1 month, 63% remained employed for more than 3 months, and 35% continued for more than 6 months. The rate of employment in the current study was slightly higher (68.8%); but the job retention rate was lower (40.4% left the job within 1 month, while only 38.6% sustained the placement for more than 3 months).

Two major reasons might account for the differences. First, in this study, individuals who expressed an interest in employment were given a client-screening interview to ensure that they had the prerequisite work potential, so the results may differ from similar studies that included individuals who had no intention of seeking employment or had limited potential for work. Secondly, the SCE programme in Hong Kong put more importance on rapid job search and placement, development of relevant work experience, and community reintegration than on individual preference, which may account for the lower job tenure.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The trial described here is a pilot study and lacks a control group for comparison. More vigorous research methodology such as a randomised controlled trial may be used to determine the programme’s effectiveness in future research. In order to enhance the generalisability of the intervention programme, a well-defined population of individuals in terms of duration of psychiatric illness, diagnosis (degree of functional disability rather than category), and number of previous hospitalisations, may be of value.

Several recognised significant predictors of employment success are not included in the study, for example, previous employment history, individual skills level, and mental status prior to employment. Future research should consider the correlation of these factors with the vocational outcomes. Furthermore, the effects of the SCE programme on non- vocational outcomes, such as psychiatric symptoms, readmission to hospital, self esteem, and quality of life are also important aspects of future research. Despite its limitations, this study indicates that SCE can be an effective approach to help individuals with chronic mental illness to achieve competitive employment.

CONCLUSION

Individuals with chronic mental illness have the same aspirations for work prospects as others in our society. Difficulty in obtaining and maintaining competitive employment is seen as one of the defining features of individuals with chronic mental illness.1 The results of the present study provide evidence to support the use of the SCE programme to enhance the vocational outcomes of individuals with chronic mental illness. The findings not only provide useful information for empirical comparison across studies, but also facilitate the future development of the SCE programme in Hong Kong. The continuous improvement of the quality of the SCE service for individuals with chronic mental illness requires more evidence-based information on better-defined populations, services, and support.

REFERENCES

- Scheid TL, Anderson C. Living with chronic mental illness: under- standing the role of work. Community Ment Health J 1995;31: 163-176.

- Ip F, Pearson V, Ho KK, Lo E, Tong H, Yip N. Employment for people with a disability in Hong Kong: opportunities and Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong; 1995.

- Anthony WA, Buell GJ. Predicting psychiatric rehabilitation outcome using demographics: a replication. J Counsel Psychol 1974;21:421-422.

- Anthony WA, Jansen MA. Predicting the vocational capacity of the chronically mentally ill. Am Psychol 1984;5:537-549.

- Anthony WA, Liberman RP. The practice of psychiatric re- habilitation: historical, conceptual, and research base. Schizophr Bull 1986;12:542-559.

- Jacobs HE, Wissusik D, Collier D, Burkeman D. Correlations between psychiatric disabilities and vocational outcome. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992;43:365-369.

- Danley KS, Rogers ES, MacDonald K, Anthony W. Supported em- ployment for adults with psychiatric disability: results of an innovative demonstration project. Rehabil Psychol 1994;39:269-276.

- Drake RE, Becker DR, Biesanz JC, Torrey WC, McHugo GJ, Wyzik PF. Rehabilitation day treatment vs. supported employment: I. vo-cational outcomes. Community Ment Health J 1994;30: 519-532.

- Bond GR, Dietzen LL, McGrew JH, Miller LD. Accelerating entry into supported employment for persons with severe psychiatric disabilities. Rehabil Psychol 1995;40:74-94.

- Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Becker DR, Anthony WA, Clark RE. The New Hampshire study of supported employment for people with severe mental illness: vocational outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996;64:391-399.

- Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, Vogler KM. A fidelity scale for the individual placement and support model of supported employment. Rehabilitation Counsel Bull 1997;40:265-284.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- Wehman P. Supported competitive employment for persons with severe disabilities. J Appl Rehabil Counsel 1986;17:24-29.

- Becker DR, Drake RE. Individual placement and support: a community mental health center approach to vocational rehabilitation. Community Ment Health J 1994;30:193-206.

- Wehman P, Melia R. The job coach: function in transitional and supported employment. Am Rehabil 1985;11:4-7.

- Cook JA, Pickett SA. Recent trends in vocational rehabilitation for people with psychiatric disability. Am Rehabil 1994;20:2-12.

- Cook AJ, Rosenberg H. Predicting community employment among persons with psychiatric disability: a logistic regression analysis. J Rehabil Admin 1994;18:6-22.

- McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Becker DR. The durability of supported employment effects. Psychiatr Rehabil J 1998;22:55-61.

- Bell MD, Lysaker PH, Milstein RM. Clinical benefits of paid work activity in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1996;22:51-67.

- Fabian E. Longitudinal outcomes in supported employment: a survival analysis. Rehabil Psychol 1992;37:23-35.

- Shafer MS, Huang HW. The utilization of survival analyses to evaluate supported employment. J Voc Rehabil 1995;5:103-113.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Supported Employment Services, Kwai Chung Hospital, for their help in preparing the manuscript.

Mr KK Wong, PDOT, MSc, Occupational Therapist I, Kwai Chung Hospital, 3-15 Kwai Chung Hospital Road, Hong Kong, China.

Dr SN Chiu, MB, ChB, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM(Psychiatry), Senior Medical Officer, Kwai Chung Hospital, 3-15

Kwai Chung Hospital Road, Hong Kong, China.

Ms LP Chiu, PDOT, Senior Occupational Therapist, Kwai Chung Hospital, 3-15 Kwai Chung Hospital Road, Hong Kong, China.

Ms SW Tang, PDOT, MBA, Occupational Therapist I, Kwai Chung Hospital, 3-15 Kwai Chung Hospital Road, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Mr KK Wong

Occupational Therapy Department

Kwai Chung Hospital 3-15 Kwai Chung Hospital Road

Hong Kong, China