East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2018;28:85-94

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr Yong Kang Cheah, PhD, School of Economics, Finance and Banking, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia.

Dr Mohd Azahadi, MPH, Centre for Burden of Disease Research, Institute for Public Health, Malaysia.

Dr Siew Nooi Phang, PhD, School of Government, College of Law, Government and International Studies, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia.

Dr Noor Hazilah Abd Manaf, PhD, Faculty of Economics and Management Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia, Malaysia.

Address for correspondence: Dr Yong Kang Cheah, School of Economics, Finance and Banking, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia.

Email: yong@uum.edu.my / cheahykang@gmail.com

Submitted: 4 June 2017; Accepted: 10 January 2018

Abstract

Objective: To determine the association of suicidal ideation with demographic, lifestyle, and health factors, using data from National Health and Morbidity Survey 2011 (NHMS 2011) of Malaysia.

Methods: The NHMS 2011 included 10,141 respondents. Independent variables of suicidal ideation were income, age, household size, sex, ethnicity, education, marital status, smoking, physical activity, and self-rated health. The risk factors of suicidal ideation were determined using logistic regression analysis.

Results: In the pooled sample, suicidal ideation was associated with age, sex, ethnicity, and self-rated health, but not associated with income, household size, education, physical activity, or smoking. Conclusion: The likelihood of having suicidal ideation is positively associated with young adults, women, Indians, and those with poor self-rated health.

Key words: Age groups; Health; Life style; Sex; Suicidal ideation

Introduction

Depression and chronic stress are responsible for various mental health problems,1,2 and can lead to suicidal ideation.3 Suicidal ideation is a major public health concern worldwide, especially in developing countries like Malaysia. In 2012, the suicide rate in Malaysia increased sharply, with an estimated 772 deaths by suicide.4 This is equivalent to 3 deaths by suicide for every 100,000 deaths. Suicide is also a serious problem in elderly people. From 2008 to 2009, the prevalence of suicide in Malaysia increased from 290 to 328.5

Demographic factors are associated with suicidal ideation.6 In both aggregate- and individual-level studies,7-15 low income or low gross domestic product per capita is consistently associated with suicidal ideation.7-12,14 This is likely because poor people have poor access to healthcare services and thus have lower well-being.7 Suicidal ideation is also closely related to divorce and small household size because loneliness and lack of integration can lower happiness.7,11,12,14 Younger age and low education level are also associated with suicidal ideation.14 In terms of health and lifestyle factors, smoking and illness resulting in absence from work can increase the probability of having suicidal ideation.12,14 Those who are physically inactive are more likely to have suicidal ideation than those with high levels of physical activity.14 Physical activity promotes better health and thus better well-being. Frequent engagement in physical activity increases the chance of socialising with people and thus self-esteem.16

There are few studies on suicidal ideation in developing countries. In a meta-analysis of studies in China, risk factors of suicidal ideation were reported to be female sex, poor academic performance, illness, smoking, and alcohol drinking.13 We aimed to determine the association of suicidal ideation with demographic, lifestyle, and health factors using data from the Malaysian National Health and Morbidity Survey 2011 (NHMS 2011).17

Methods

This study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR-10- 757-6837). Informed consent was obtained from every respondent or his/her guardians (for minors or disabled) in the presence of a witness. The NHMS 2011 was carried out by the Ministry of Health of Malaysia between April and July 2011.17 It was based on two-stage stratified sampling. The first-stage sampling was based on geographically contiguous areas of the country (enumeration blocks). The second-stage sampling was based on living quarters. Each enumeration block consisted of 80 to 120 living quarters, with an average population of 500 to 600. A total of 12 living quarters were randomly selected from each of the 794 enumeration blocks. All persons within the selected living quarters were interviewed face-to-face. The overall response rate was 93%, with 10,141 respondents included.

Suicidal ideation was determined by asking: “In the past 30 days, have you thought about suicide?” A ‘yes’ response was considered to have suicidal ideation. Based on a study,14 independent variables of suicidal ideation were income, age, household size, sex, ethnicity, education, marital status, smoking, physical activity, and self-rated health. Monthly income (in Malaysian Ringgit [RM]) was categorised into ≤999, 1000-2999, 3000-5999, and ≥6000.18-20 Age and household size were continuous variables. Ethnicity was categorised into Malay, Chinese, Indian, and others. Education level was categorised

into tertiary (≥12 years), secondary (7-11 years), and primary (≤6 years). Marital status was categorised into married, widowed/divorced, and single. Those who were unattached were expected to display different well-being behaviours than those who were attached because of a lack of intimate relationships.21 Smokers were defined as those who answered ‘yes’ to the question “Do you currently smoke?” Physical activity was determined by asking “In the past 7 days, on how many days have you engaged in vigorous- or moderate-intense physical activity for at least 10 minutes per session?” The intensity of physical activity was determined by metabolic equivalents (METS), which is the ratio of the exercise metabolic rate to the metabolic rate when sitting quietly (defined as 1 MET). Physical activity

of >6 METS was categorised as vigorous. Those who spent at least 150 minutes per week in moderate or 60 minutes per week in vigorous physical activities were considered to be physically active. Self-rated health was determined by asking “In general, how would you rate your health today?” Those who answered ‘very good’ or ‘good’ were grouped as ‘excellent’, ‘moderate’ as ‘fair’, and ‘not good’ or ‘very bad’ as ‘poor’.22 The substance abuse and alcohol drinking variables were not included in the analyses, because few respondents confessed to consuming drugs and alcohol, given that these are prohibited among Muslims in Malaysia.

Those with or without suicidal ideation were compared using t test (for income, age, and household size) or Pearson χ2 test (for sex, ethnicities, education, marital status, physical activity, smoking, and self-rated health). Logistic regression analysis was used to determine association between suicidal ideation and other variables, assuming that errors had logistic distribution. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

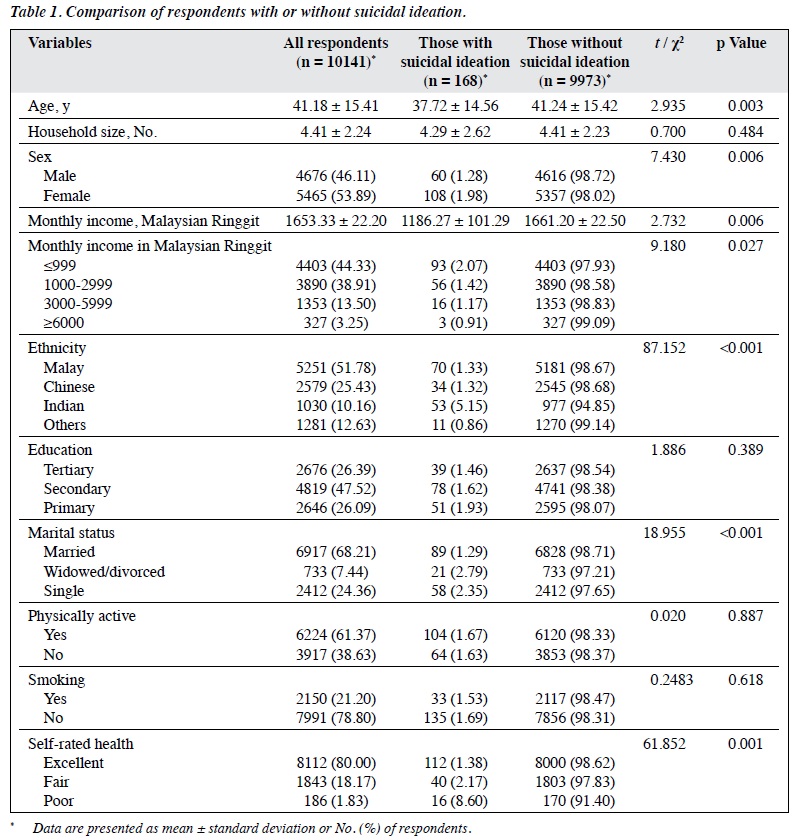

Of 10,141 respondents, 168 (1.66%) had suicidal ideation (Table 1). Overall, 53.89% of the respondents were females. The mean age of the respondents was 41.18 years. The mean household size was 4.41 members. Most respondents reported having monthly income (in RM) of ≤999 (44.33%), followed by 1000-2999 (38.91%), 3000- 5999 (13.50%), and ≥6000 (3.25%). Most respondents were Malay (51.78%), followed by Chinese (25.43%), Indians (10.16%), and others (12.63%). Most respondents reported having completed secondary education (47.52%), followed by tertiary education (26.39%) and primary education (26.09%). Most respondents were married

(68.12%), followed by single (24.36%) and widowed/ divorced (7.44%). Most respondents were physically active (61.37%). Only 21.20% were smokers. Most respondents had excellent self-rated heath (80.00%), followed by fair (18.17%) and poor (1.83%) self-rated heath.

Compared with those without suicidal ideation, those with suicidal ideation were younger (37.72 vs 41.24 years, p = 0.003) and of lower monthly income (RM1186.27 vs RM1661.20, p = 0.006).

Suicidal ideation was more frequently reported in women than in men (1.98% vs 1.28%, p < 0.006), in the lowest income group (≤RM999) than in the highest income group (≥RM6000) [2.07% vs 0.91%, p = 0.027], in Indians than in Malays, Chinese, or others (5.15% vs 1.33% vs 1.32% vs 0.86%, respectively, p < 0.001), in those who were widowed/divorced or single than in those who were married (2.79% vs 2.35% vs 1.29%, respectively, p < 0.001), and in those who rated their health as poor than in those who rated their health as fair or excellent (8.60% vs 2.17% vs 1.38%, respectively, p = 0.001).

In a multivariable regression model, the likelihood ratio was 139 (p = 0.01) and thus all the independent variables were jointly significant. Approximately 98.30% of the outcomes were predicted correctly and thus the model was well-specified. Age was negatively associated with suicidal ideation and remained so after controlling for all other factors. Women were more likely to have suicidal ideation than men. Indians were more likely to have suicidal ideation than Malays, Chinese, or others. Those who rated their health as poor were more likely to have suicidal ideation than those who rated their health as excellent or fair (Table 2).

Risk factors associated with suicidal ideation by ethnicity are presented in Table 3. Among Malays, being married was negatively associated with the odds of having suicidal ideation, but it became non-significant after controlling for all other variables. The negative association between age and the odds of having suicidal ideation was evidence in Malays and Chinese. Chinese who had a larger household size were less likely to have suicidal ideation than their counterparts with a smaller household size. Indians who had tertiary or secondary education were less likely to have suicidal ideation than their counterparts with primary education. Among Malays and Indians, excellent and fair self-rated health was negatively associated with the odds of having suicidal ideation. The associations between suicidal ideation and demographic, lifestyle, and health factors were slightly different across different ethnic groups.

Risk factors associated with suicidal ideation by sex are presented in Table 4. For both sexes, age was negatively associated with the odds of having suicidal ideation and remained so after controlling all other variables. Malays, Chinese, and other ethnicity were less likely to have suicidal ideation than Indians. In both sexes, being married was negatively associated with the odds of having suicidal ideation. Those with excellent or fair self-rated health had lower odds of having suicidal ideation than their counterparts with poor self-rated health.

Risk factors associated with suicidal ideation by age groups are presented in Table 5. Respondents were categorised in 4 different age groups (18-30 years, 31-40 years, 41-50 years, and ≥51 years).23,24 Among those aged ≥51 years, household size was negatively associated with the odds of having suicidal ideation after controlling for all other variables. There were ethnic differences in suicidal ideation across all age groups, except for those aged 31-40 years. Indians displayed the highest odds of having suicidal ideation. Respondents aged 31-40 years and 41-50 years with tertiary or secondary education were less likely to have suicidal ideation than their counterparts with primary education. Respondents aged 31-40 years who were widowed/divorced were more likely to have suicidal ideation than those who were single. Respondents aged 18-30 years, 31-40 years, and ≥51 years with excellent or fair self-rated health were negatively associated with the odds of having suicidal ideation, even after controlling for all other variables.

Discussion

In the present study, age, sex, ethnicity, and self-rated health were associated with suicidal ideation. Other important factors such as income and education were not associated with suicidal ideation. Education level was a significant factor in Indians and the age group of 41-50 years, but it was not significant in the pooled sample and other subsamples. A meta-analysis of studies in China reported that low education and poor economic background are not associated with suicidal ideation.13 However, in Indian populations, education is significantly associated with suicidal ideation.25 In low- and middle-income countries, socioeconomic factors (including education and income) are associated with suicide attempts.26

In a study using the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, age is negatively associated with the propensity to have suicidal ideation among women, but it is positively associated among men.14 Young adults are associated with higher suicide attempt rates in eastern India and Malaysia,25,27 but not in Bali, Indonesia.28 A meta-analysis reported no age difference in the odds of suicidal ideation.6 In the present study, age was negatively associated with suicidal ideation in the overall sample, possibly because younger people tend to have more worries about career advancement, job responsibility, and household commitments and live a more hectic lifestyle than older people. Consequently, young adults, especially those living in the urban areas may have higher levels of stress, which can lead to suicidal ideation. Future national policies, especially those related to health and youth should include measures that may reduce suicidal ideation among young adults. It is imperative that concerted efforts by the government should be made to educate the youth to cope with stressful living. The targeted ethnic groups should be Malay and Indian rather than Chinese.

A meta-analysis of studies in China reported that women are more likely than men to have suicidal ideation.13 Similarly, a study using data from Danish longitudinal registers reported that women tend to have a higher risk than men of suicidal ideation.12 In eastern India and Bali, Indonesia, women are more likely than men to think about suicide.25,28 In Malaysia, women are more likely to suffer from depression and thus have a higher propensity than men to attempt suicide.27 The results of the present study are consistent with these previous findings; there are significant sex differences in suicidal ideation. Although women are more likely to have suicidal ideation than men, suicide rates are higher in men than in women. Men are more likely than women to die by suicide, according to a systematic review study in Malaysia.29

There are ethnic differences in suicidal ideation as well as socioeconomic differences across ethnicities in suicidal ideation in Atlanta, Georgia, USA.10 In Malaysia, Indians are more likely than Malays or Chinese to attempt suicide and to die by suicide.27,29 In the present study, Indians displayed the highest likelihood of having suicidal ideation, probably because of the unequal privileges afforded to the various ethnic groups. The government should not disregard this inequality between ethnic groups, as it may be related to the tendency to have suicidal ideation. Other plausible factors include religion, culture, poverty, and alcoholism.27 These factors should be further tested by in-depth qualitative studies. Policies directed at reducing suicidal ideation among Indians can yield desirable outcomes. Extra attention should be paid to Indians who are aged 18-30 years, 41-50 years, or ≥51 years, because these age groups have a high propensity for suicidal ideation.

Individuals who have health problems that can result in absence from work have a higher risk of suicidal ideation than their counterparts who do not have such health problems.12 Similarly, physical illness is positively associated with suicidal ideation.13 These previous findings are consistent with those of the present study, which found self-rated health is inversely associated with suicidal ideation. The present study used self-rated health rather than illness as a proxy for health. Self-rated health has high reliability and can accurately measure an individual’s heath condition.22 Future studies may consider using more health variables to explore the association of health with suicidal ideation. The government should introduce a variety of health promotion programmes, with a focus on Malay and Indian ethnic groups, in order to reduce suicidal ideation.

The present study has several limitations. There may have been reporting error, as all information obtained from the survey, including suicidal ideation, was self-reported. Several mental health and lifestyle variables were not included in the analysis, such as depression, life event, self- harm history, family suicide history, substance abuse, and alcohol drinking. Because the present study was a cross- sectional study, the causal effects of the demographic, lifestyle, and health factors on suicidal ideation cannot be identified. Suicidal ideation may not necessarily result in suicide. Despite these limitations, the large dataset and rigorous statistical methods used can ensure inference and thus assist formulation of policies to reduce suicidal ideation.

Conclusion

Suicidal ideation is associated with younger age, female sex, Indian ethnicity, and poor self-rated health. This finding is useful for government agencies to formulate policies.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health, Malaysia for his permission to use data from the National Health and Morbidity Survey 2011. Research support from the Population Studies Unit of University of Malaya is gratefully acknowledged (IF002-2014).

Declaration

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Downward P, Rasciute S. An economic analysis of the subjective health and well-being of physical activity? In: Rodriguez P, Kesenne S, Humphreys BR, editors. The Economics of Sport, Health and Happiness: The Promotion of Well-being through Sporting Activities. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; 2011:33-53. cross ref

- Chou LF, Chu CC, Yeh HC, Chen J. Work stress and employee well-being: the critical role of Zhong-Yong. Asian J Soc Psychol 2014;17:115-27. cross ref

- Daly MC, Wilson DJ. Happiness, unhappiness, and suicide: an empirical assessment. J Eur Econ Assoc 2009;7:539-49. cross ref

- World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide: a Global Imperative. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. National Suicide Registry Malaysia (NSRM): Annual Report for 2009. Kuala Lumpur: NSRM; 2011.

- Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull 2017;143:187-232. cross ref

- Neumayer E. Socioeconomic factors and suicide rates at large-unit aggregate levels: a comment. Urban Stud 2003;40:2769-76. cross ref

- Taylor R, Page A, Morrell S, Harrison J, Carter G. Mental health and socio-economic variations in Australian suicide. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:1551-9. cross ref

- Rehkopf DH, Buka SL. The association between suicide and the socio- economic characteristics of geographical areas: a systematic review. Psychol Med 2006;36:145-57. cross ref

- Purselle DC, Heninger M, Hanzlick R, Garlow SJ. Differential association of socioeconomic status in ethnic and age-defined suicides. Psychiatry Res 2009;167:258-65. cross ref

- 1 Kolves K, Milner A, Varnik P. Suicide rates and socioeconomic factors in Eastern European countries after the collapse of the Soviet Union: trends between 1990 and 2008. Sociol Health Illn 2013;35:956-70. cross ref

- Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB. Suicide risk in relation to socioeconomic, demographic, psychiatric, and familial factors: a national register-based study of all suicides in Denmark, 1981-1997. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:765-72. cross ref

- Li Y, Li Y, Cao J. Factors associated with suicidal behaviors in mainland China: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2012;12:524. cross ref

- Song HB, Lee SA. Socioeconomic and lifestyle factors as risks for suicidal behaviour among Korean adults. J Affect Disord 2016;197:21-8. cross ref

- Jaisoorya TS, Geetha D, Beena KV, Beena M, Ellangovan K, Thennarasu K. Prevalence and correlates of psychological distress in adolescent students from India. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2017;27:56-62.

- Huang H, Humphreys BR. Sports participation and happiness: evidence from US micro data. In: Rodriguez P, Kesenne S, Humphreys BR, editors. The Economics of Sport, Health and Happiness: The Promotion of Well-being through Sporting Activities. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; 2011:163-83. cross ref

- Institute for Public Health. National Health and Morbidity Survey 2011: Non-communicable Diseases. Putrajaya: Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2011.

- Cheah YK, Tan AK. Determinants of leisure-time physical activity: evidence from Malaysia. Singapore Econ Rev 2014;59:1450017. cross ref

- Cheah YK. Socioeconomic determinants of alcohol consumption among non-Malays in Malaysia. Hitotsubashi J Econ 2015;56:55-72.

- Cheah YK. Factors affecting use of preventive medical care: an exploratory case study using Penang data. Inst Econ 2016;8:84-101.

- Dolan P, Peasgood T, White M. Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. J Econ Psychol 2008;29:94-122. cross ref

- Cheah YK. An exploratory study on self-rated health status: the case of Penang, Malaysia. Malays J Econ Stud 2012;49:141-55.

- Cheah YK. Socioeconomic disparities in physical activity participation: an exploratory study using Malay sample. Asia Pac Soc Sci Rev 2015;15:93-107.

- Cheah YK, Moy FM, Loh DA. Socio-demographic and lifestyle factors associated with nutrition label use among Malaysians adults. Br Food J 2015;117:2777-87. cross ref

- Halder S, Mahato AK. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who attempt suicide: a hospital based study from Eastern India. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2016;26:98-103.

- Knipe DW, Carroll R, Thomas KH, Pease A, Gunnell D, Metcalfe C. Association of socio-economic position and suicide/attempted suicide in low and middle income countries in South and South-East Asia: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1055. cross ref

- Sinniah A, Maniam T, Oei TP, Subramaniam P. Suicide attempts in Malaysia from the year 1969 to 2011. ScientificWorldJournal 2014;2014:718367. cross ref

- Kurihara T, Kato M, Reverger R, Tirta IG. Suicide rate in Bali. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009;63:701. cross ref

- Armitage CJ, Panagioti M, Abdul Rahim W, Rowe R, O’Connor RC. Completed suicides and self-harm in Malaysia: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2015;37:153-65. cross ref