East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2018;28:95-100

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Clarice Yi Wen Chan, GCE A levels, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Samantha Wei Lee Yong, GCE A levels, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abhishek Subodh Mhaisalkar, GCE A levels, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Dr Gwen Li Sin, MD, MMED (Psychiatry), Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

Dr Shi Hui Poon, MD, MRCPsych (UK), Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

Dr Shian Ming Tan, MD, MMED (Psychiatry), Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

Address for correspondence: Dr Shian Ming Tan, Singapore General Hospital, Outram Road, Singapore 169608. Email: tan.shian.ming@singhealth.com.sg

Abstract

Objective: To review the mental capacity assessment of in-patients referred to consultation-liaison psychiatrists and to compare the assessment first made by primary care physicians.

Methods: Medical records of in-patients who were referred to consultation-liaison psychiatrists for mental capacity assessment between May and October 2015 were retrospectively reviewed. Assessment was first made by a primary care physician; complex cases were referred to a consultation-liaison psychiatrist. Audit of each case note was conducted independently by at least two of the authors.

Results: Medical records of 37 female and 26 male in-patients aged 24 to 91 (mean, 68.2) years were audited. Only 33.3% of these patients had no psychiatric diagnosis. Overall, assessments by primary care physicians were suboptimal. Assessments by consultation-liaison psychiatrists were more detailed, with documentation of mental capacity (93.7%) and psychiatric diagnosis (88.9%). Nonetheless, patient wishes and beliefs were poorly documented (19.0%), as were whether the patient had a lasting power of attorney or a court-appointed deputy (6.3%) and whether the patient had made advance care planning (0%).

Conclusion: Overall, mental capacity assessment was inadequately performed by primary care physicians and consultation-liaison psychiatrists. More work needs to be done to engage, educate, and empower all stakeholders involved.

Key words: Clinical audit; Mental competency

Introduction

In Singapore, the Mental Capacity Act sets a legal framework to allow individuals aged ≥21 years to appoint in advance, trusted person(s) to make decisions (concerning personal welfare, healthcare, and assets) on their behalf in the event they lose mental capacity (temporarily or permanently) by signing a lasting power of attorney to legalise appointment of proxies. Should one become mentally incapacitated before making a lasting power of attorney, the Act allows the court to appoint a deputy to make decisions.1 This legislation was first passed in the United Kingdom in 2005 to address caretaker concerns about the lack of legal guidance in decision making. It has since been adopted by New Zealand, Australia, Ireland, and Singapore.

Advance care planning is a non-legal series of discussion among a patient, trusted person(s), and physicians to facilitate sharing and recording of the patient’s personal beliefs, values, and goals of care. It guides the trusted person(s) and physicians in decision making should the patient become mentally incapacitated or be unable to make/convey decisions.2

Primary care physicians are required to assess the mental capacity of the patient, with the presumption that the patient has mental capacity. They must determine whether the patient is able to understand, retain, and weigh the relevant information as part of the decision-making process and if he/she can communicate said information. Details should be documented in the case notes, along with the impression of the patient’s mental capacity and reasons to support the judgement, as should details of any lasting power of attorney or advance care planning and consultations with trusted persons on patient wishes.3

Nonetheless, inadequate assessment has resulted in incapacitated patients not being assessed as such, or being treated without true valid consent,4,5 with a lack of orminimal documentation.6 Patients may be determined to beincapacitated if the physician sets the threshold too high anddoes not take all reasonable steps to improve the patient’sdecision-making capacity. This raises concerns about abuseof the assessment. Patients are then vulnerable to coercionfrom family members and physicians, and their freedom ofaction severely restricted.7

In Singapore, primary care physicians assess the mental capacity of every patient; a second opinion from a consultation-liaison psychiatrist is sought when there is any doubt, usually if the patient has a mental disorder. This study aimed to review the mental capacity assessment of in-patients referred to consultation-liaison psychiatrists and to compare the assessment first made by primary care physicians.

Methods

This retrospective study was approved by the SingHealth Central Institutional Research Board. Patient consent was waived. Medical records of Singapore General Hospital in-patients who were referred to consultation-liaison psychiatrists for mental capacity assessment between May and October 2015 were retrospectively reviewed. Assessment was first made by a primary care physician; complex cases were referred to a consultation-liaison psychiatrist.

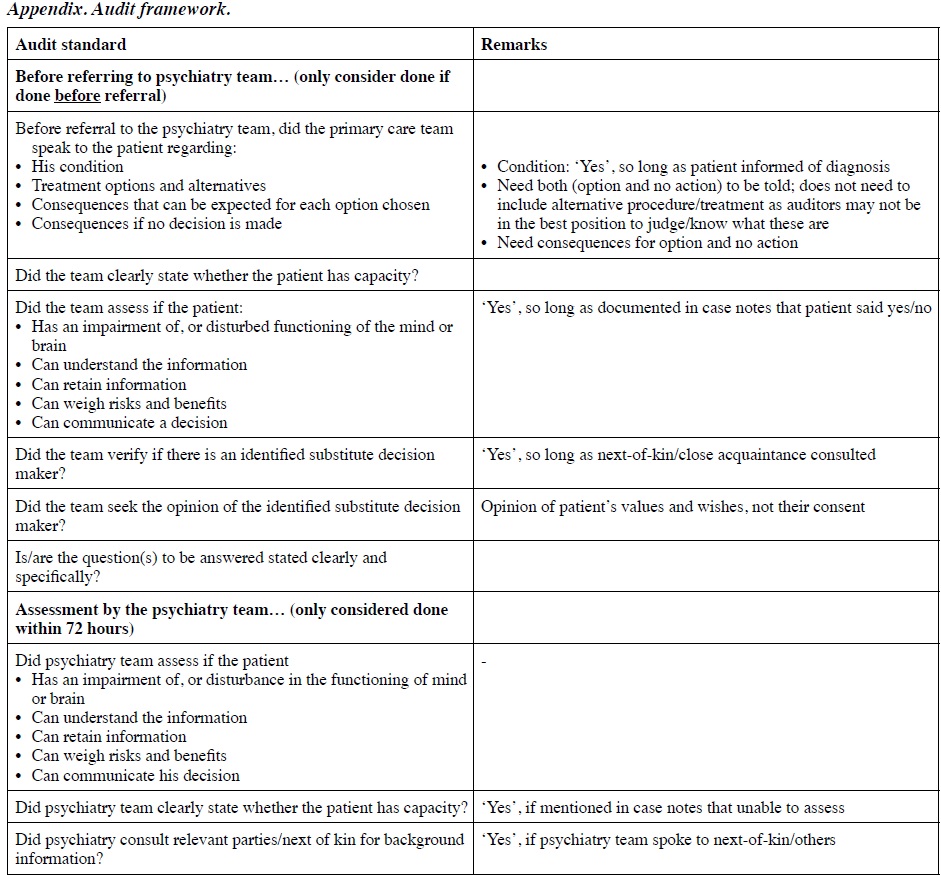

Two of the authors independently reviewed the previous assessment tools and standards8 and each developed an audit framework. The final audit framework was developed after consensus on what was culturally and legally relevant in the local context (Appendix). Patient characteristics were recorded, along with whether patient family and/or legal representatives (e.g. lasting power of attorney) were consulted.

Audit of each case note was conducted independently by at least two of the authors. Responses were tallied and discrepancies resolved by consensus. Data were dichotomised according to whether they had been elicited or not; data that were not documented were considered not elicited. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics. Frequency of responses and trends were tabulated.

Results

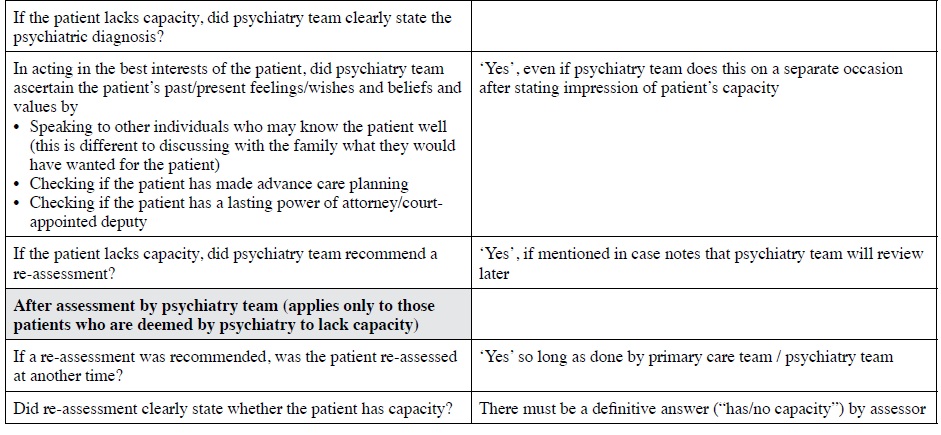

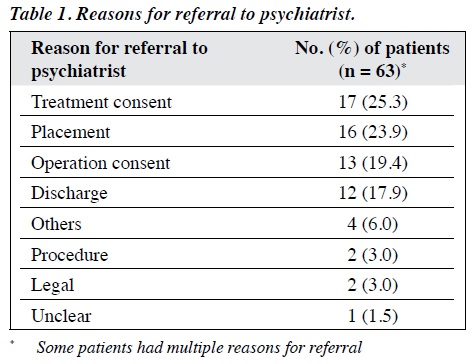

Medical records of 37 female and 26 male in-patients aged 24 to 91 (mean, 68.2) years were audited. Requests for assessment were sometimes incomplete and were embedded in referrals for psychiatric management. The main reasons for referral for mental capacity assessment were: treatment consent (25.3%), placement (23.9%), operation consent (19.4%), and discharge (17.9%) [Table 1]. Of these patients, 25.4% were diagnosed with dementia and cognitive impairment and 15.9% with delirium. Only 33.3% had no psychiatric diagnosis (Table 2).

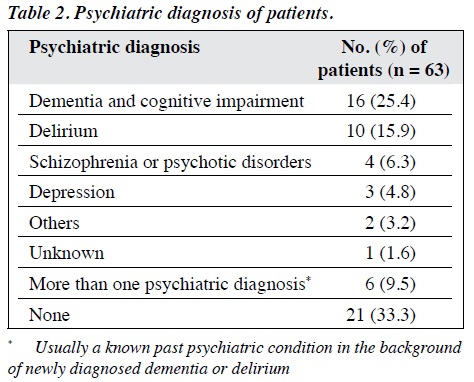

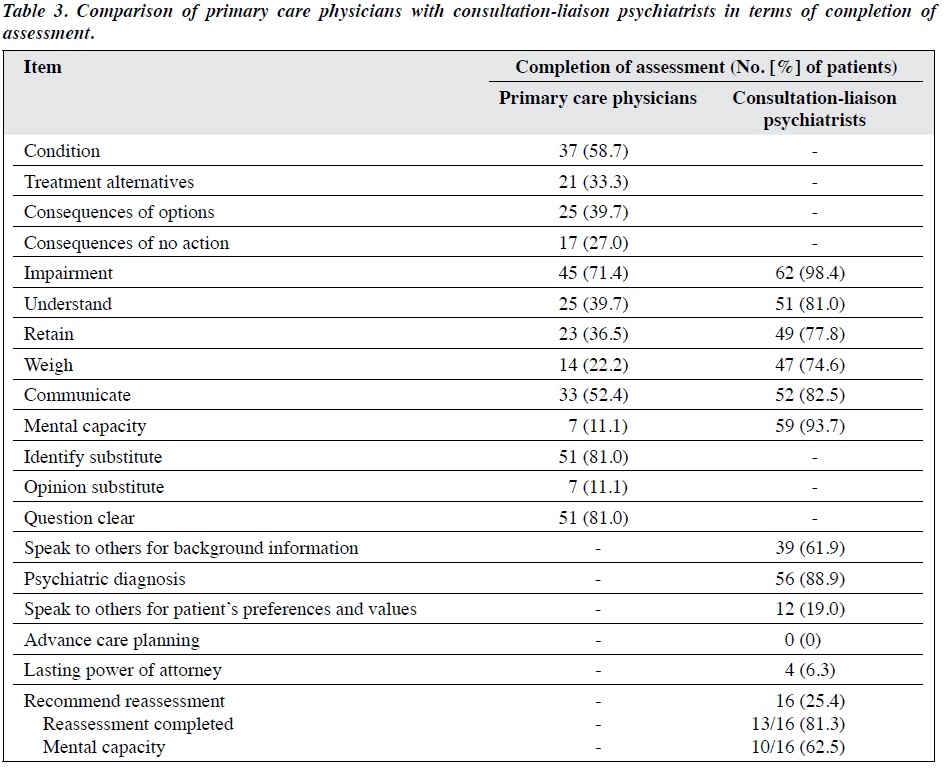

Prior to referral to the psychiatric team, most primary care physicians had determined if the patient had impaired functioning of the mind (71.4%) and had actively engaged the patient’s family or close acquaintances in patient care (80.9%) [Table 3]. Nonetheless, they seldom sought the family’s opinion of the patient’s values and pre-expressed wishes (11.1%). In contrast, assessments conducted by the psychiatric team were more detailed, with documentation of mental capacity (93.7%) and psychiatric diagnosis (88.9%). Nonetheless, patient wishes and beliefs were poorly documented (19.0%), as were whether the patient had a lasting power of attorney or a court-appointed deputy (6.3%) and whether the patient had made advance care planning (0%).

Discussion

Documentation of mental capacity assessment by primary care physicians was inadequate, consistent with findings of previous audits.4,6 Inadequate documentation may be due to time pressure or reluctance to alter routine care and undermine the doctor-patient relationship.4

Assessment of mental capacity is in two stages: (1) establishing impairment of the mind and that (2) the impairment causes inability to make a decision. In our audit, primary care physicians were particularly inadequate at assessing how the impairment affected the patient’s ability to understand/retain/weigh information and communicate the decision. One explanation is that most primary care physicians erroneously assume that patients ‘automatically’ lack mental capacity in the presence of an active psychiatric illness.9 Primary care physicians may be ill-equipped to assess mental capacity based on the Code of Practice. In a survey to assess doctors’ knowledge of the Act, only 70% of doctors in an emergency department were able to outline the steps involved in mental capacity assessment.10 It seems that doctors have failed to keep pace with rapidly evolving medical practice and have not developed the appropriate new skill sets.

In our audit, only 11.1% of primary care physicians documented their impression of the patient’s mental capacity prior to referral to the psychiatry team. They may have felt that there was no role for them given that they had already solicited input from the psychiatry team. Nonetheless, there is no mandate that mental capacity assessment be performed only by a psychiatrist. Primary care physicians are qualified to perform mental capacity assessment11 because (1) they know the patient’s medical circumstances and the question to be decided; (2) they are in the best position to know the patient’s and family’s values and cultural and religious views; (3) they know the patient’s medical history so the assessment is longitudinal based on multiple interactions; and (4) they are in the best position to re-evaluate mental capacity because of their ongoing medical relationship with the patient. Psychiatrists are no better at assessing mental capacity than physicians.12

Documentation of informed consent was scant. In an audit of 1057 outpatients in the offices of primary care physicians and surgeons, only 9% were deemed to have the necessary information to make an informed decision.13 Among 141 cases in whom orthopedic surgical interventions were discussed, no case had all elements fully discussed, with only 62% being informed of alternatives and 59% advised about any pros and cons.14 The concept of informed consent is based on the ethical principle of the right to self-determination. Informed consent means that patients must be given options to choose, and not just information about one line of treatment. Although mental capacity of our patients is likely to be questionable, omission of informed consent based on a doctor’s impression of the patient’s mental capacity cannot be justified. Such cases are contentious and increase the risk of litigation.

Consultation-liaison psychiatrists rarely enquired patients about advance care planning or lasting power of attorney. Even when a substitute decision-maker was identified, discussion invariably focused on what the substitute decision-maker wanted for the patient, not what the patient wanted based on their prior wishes and values. Most patients who lacked mental capacity did not have a reassessment recommended or completed. Reasons for this include limited understanding of the Act and their obligations,15 and the belief that patients do not utilise the provisions of the Act. This inevitably undermines the intention of the Act to promote patient autonomy in decisions related to care, treatment, and well-being.

There are limitations to our study. Assessments that did not refer to consultation-liaison psychiatrists were not audited. It is possible that primary care physicians had performed a complete assessment, and that assessment of the referred cases was incomplete because the primary care physicians assumed that it would be completed by the consultation-liaison psychiatrists. It is possible that assessments were indeed thorough verbally, just without documentation in the case notes. The issue is thus not inadequate assessment but rather shoddy documentation. In addition, the findings of this local audit may not be applicable to other regions. Nonetheless, we separately audited the performance of the primary care physicians and consultation-liaison psychiatrists to explore the pitfalls committed by the former and the added value of the latter.

Primary care physicians should adequately document their assessment of mental capacity before referring patients for psychiatry consultation. Information should be made accessible to enhance clinician adherence to the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice. The use of a structured assessment format is recommended. A systematic review has evaluated several assessment tools.16 The Aid to Capacity Evaluation is an eight-question tool that takes about 10 to 20 minutes to complete; it has good agreement with assessment by a forensic psychiatrist.17 The tool is mainly used in Canada but can be adapted for more widespread use. A flowchart should be made available to assist clinicians with the due process when arriving at decisions in the best interests of an incapacitated individual. Patients should be given written information about advance care planning and the Act regarding execution of lasting power of attorney. They should be engaged early in advance care planning based on their wishes and intent rather than deferring to the last minute.

Conclusion

Mental capacity assessment was inadequately performed by primary care physicians and consultation-liaison psychiatrists. More work is necessary to engage, educate, and empower all stakeholders involved.

Acknowledgement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Mental Capacity Act (Chapter 177A). Singapore Statutes Online; 2008.

- Advance Care Planning. Agency of Integrated Care. Singapore Silver Pages. National Medical Ethics Committee; 2009.

- Code of Practice: Mental Capacity Act (Chapter 177A). Office of the Public Guardian; 2008.

- Sleeman I, Saunders K. An audit of mental capacity assessment on general medical wards. Clin Ethics 2013;8:47-51. cross ref

- Spencer BW, Wilson G, Okon-Rocha E, Owen GS, Wilson Jones C. Capacity in vacuo: an audit of decision-making capacity assessments in a liaison psychiatry service. BJPsych Bull 2017;41:7-11. cross ref

- Sorinmade O, Strathdee G, Wilson C, Kessel B, Odesanya O. Audit of fidelity of clinicians to the Mental Capacity Act in the process of capacity assessment and arriving at best interests decisions. Qual Ageing Older Adults 2011;12:174-9. cross ref

- Stewart R, Bartlett P, Harwood RH. Mental capacity assessments and discharge decisions. Age Ageing 2005;34:549-50. cross ref

- The British Psychological Society. Professional Practice Board and Social Care Institute for Excellence; c 2000 - 2017. Audit Tool for Mental Capacity Assessments. Available from https://www.bps.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/audit-tool-mental-capacity-assessments_0.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2018.

- Schofield C. Mental Capacity Act 2005–what do doctors know? Med Sci Law 2008;48:113-6. cross ref

- Evans K, Warner J, Jackson E. How much do emergency healthcare workers know about capacity and consent? Emerg Med J 2007;24:391-3. cross ref

- 1 Tunzi M. Can the patient decide? Evaluating patient capacity in practice. Am Fam Physician 2001;64:299-306.

- Markson LJ, Kern DC, Annas GJ, Glantz LH. Physician assessment of patient competence. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994;42:1074-80. cross ref

- Braddock CH 3rd, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. JAMA 1999;282:2313-20. cross ref

- Braddock C 3rd, Hudak PL, Feldman JJ, Bereknyei S, Frankel RM, Levinson W. “Surgery is certainly one good option”: quality and time- efficiency of informed decision-making in surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90:1830-8. cross ref

- Jackson E, Warner J. How much do doctors know about consent and capacity? J R Soc Med 2002;95:601-3. cross ref

- Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA 2011;306:420-7. cross ref

- Etchells E, Darzins P, Silberfeld M, Singer PA, McKenny J, Naglie G, et al. Assessment of patient capacity to consent to treatment. J Gen Intern Med 1999;14:27-34. cross ref