ORIGINAL ARTICLE

* Equal contribution

Mathew SC Chow, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong

Stephanie Hiu Ling Poon, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong

Kwan Lok Lui, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong Chester Chun

Yiu Chan, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong

Wendy WT Lam, School of Public Health, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong

Address for correspondence: Stephanie Hiu Ling Poon, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, the University of Hong Kong, 21 Sassoon Rd, Pok Fu Lam, Hong Kong. Email: hlspoon@hku.hk

Abstract

Objectives: To investigate the association between alcohol use and depression among university students in Hong Kong, their stress-coping methods, and their knowledge and perception of the effects of alcohol on health.

Methods: 345 full-time undergraduate students from The University of Hong Kong were invited to complete a questionnaire to assess their alcohol consumption (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, CAGE questionnaire), depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire-9), and stress-coping methods (Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory), as well as knowledge and perception of alcohol consumption on health. Multiple linear regression was used to determine significant variables associated with depressive symptoms. Multinominal logistic regression was used to determine the effect of such variables on depressive symptom caseness and AUDIT drinking risk groups.

Results: 43.2% of respondents were moderate- to high-risk drinkers, but only 23.2% were self-reported as moderate- to high-level drinkers. 57.9% of respondents had mild to severe depressive symptoms. Probable depression was more likely to occur in female students, those with higher general stress, those who do not use social support for stress-coping, and those who smoke. High-risk drinkers were more likely to occur in older students, smokers, those with higher household income, and those with higher general stress levels. Students with higher levels of depressive symptoms and higher risk of alcohol consumption were more likely to use avoidance for stress-coping. 89.5% of students considered alcohol consumption moderately to very harmful to health, but students demonstrated only moderate knowledge levels of alcohol consumption on health.

Conclusion: Alcohol consumption and depressive symptoms are prevalent among university students in Hong Kong. The use of avoidance for stress-coping is common in those with higher levels of depressive symptoms and higher-risk drinkers. Students tend to avoid seeking help for depressive symptoms and potentially take up drinking as a coping strategy. Context-specific approaches should be used when providing counselling services for student wellbeing in university settings. Further education of university students on knowledge and perception of alcohol consumption on health should be provided.

Key words: Adaptation, psychological; Alcohol drinking in college; Depression; Mental health; Stress, psychological

Introduction

Tertiary-level students have high levels of distress, mental illness (such as depression), and suicidal ideation.1-7 Systematic reviews in different countries have shown that these students have a high prevalence of depressive symptoms (11.0% to 34.0%),8-11 which is higher than the World Health Organization estimated global prevalence of depression of 4.4%.12 In Hong Kong, 68.5% of university students were reported to have mild-to-severe levels of depressive symptoms.13 In addition, alcohol use, dependence, and abuse have increased substantially among university students.14 61% of Hong Kong university students self-report alcohol use,15,16 which is lower than their counterparts in Europe or the United States.17,18

Alcohol use and depression account for a significant portion of the global disease burden in terms of disability- adjusted life-years. The onset of anxiety and depression is associated with alcohol use in excess in the general population.19 Depressive symptoms are associated with earlier onset and higher frequency of alcohol consumption.20-23 Common mental disorders (such as depression) are positively associated with alcohol drinking and misuse among the general public24 and nurses25 in Hong Kong as well as university students elsewhere.26-28

Coping strategies for psychological wellbeing vary in different population sub-groups, cultural contexts, and social behaviours,29,30 as does perception of alcohol use.31 Students are reluctant to seek help for mental health–related issues,32-34 and alcohol presents a possible coping mechanism for stress and depression.35 There is evidence that drinking to cope with negative emotions is a mediator between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related behaviour and perceptions.36-38 Thus, the present study aims to investigate the association between alcohol use and depression among university students in Hong Kong, their stress-coping methods, and their knowledge and perception of the effects of alcohol on health.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong / Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (reference: HKU/HA HKW IRB UW 18-666). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

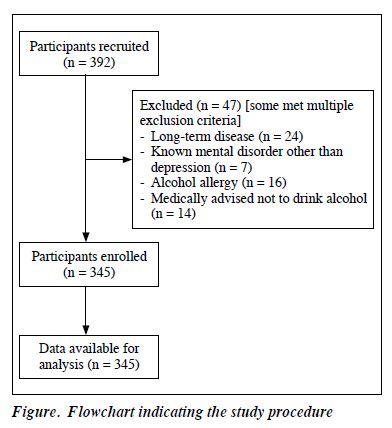

Between January and March 2019, full-time undergraduate students aged ≥18 years from the University of Hong Kong were recruited at various locations on campuses during school days. Those with known alcohol allergy, long-term disease, mental diseases other than depression, or medical advice not to drink alcohol were excluded (Figure).

Based on a study of depression in Hong Kong tertiary education institutions,13 a sample of 332 was estimated to provide 90% power to detect 68.5% ± 10% prevalence of mild-to-severe depression.

The 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)39 was used to assess the level of alcohol consumption. Total scores range from 0 to 40; scores 0 to 7 indicate low risk, 8 to 15 moderate risk, 16 to 19 high risk, and 20 to 40 likely addiction, which is in line with World Health Organization recommendations.40 Internal consistency is good for both the English (Cronbach’s alpha=0.97) and Chinese (Cronbach’s alpha=0.74) versions of AUDIT.40,41 For comparison, the four-item CAGE questionnaire42 was used to assess the level of alcohol consumption. Total scores range from 0 to 4; scores of 0 to 1 indicate low risk of problem drinking, scores of 2 to 3 indicate high suspicion of alcoholism, and a score of 4 indicates virtually diagnostic of alcoholism.43 In addition, students were asked to self-report their drinking status as non-drinkers, low-, moderate-, or high-level drinkers. Data related to circumstances and location of drinking, familial drinking habits, type and quantity of alcohol typically consumed were collected.

The nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to measure the extent and presence of depressive symptoms. It is reliable and valid and has specificity of 88% and sensitivity of 88%.44 It has been validated in the general Hong Kong populations45 and university populations.46,47 Total scores range from 0 to 27; scores of 1 to 4 indicate minimal, 5 to 9 mild, 10 to 14 moderate, 15 to 19 moderately severe, and 20 to 27 severe depressive symptoms. A cut-off score of ≥10 (range, 0-27) indicates probable depression, with a specificity of 85% and sensitivity of 88%.

The 28-item Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (COPE) Inventory was used to assess coping methods in response to stress. There were four dimensions: social support, problem solving, avoidance, and positive thinking. Scores for each item range from 1 to 4; the mean score for each dimension was calculated. The four dimensions had satisfactory psychometric properties,48 with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.64 to 0.82 and test-retest reliability of >0.42.49 The use of the four dimensions avoids dichotomisation of the inventory into adaptive or maladaptive coping,50 while preserving analytical simplicity and ease.

The current level of general stress and stress experienced at university was self-rated on a five-point Likert scale from not stressed (1) to very highly stressed (5).

Knowledge of the risk of excessive alcohol consumption to the liver, pancreas, stomach, cardiovascular system, and malignancies of the skin, breast, and bowels was assessed, as was perception of drinking behaviour and trend of alcohol use and alcohol abuse among peers. Students were asked the degree of harm to health by alcohol consumption from ‘not harmful’, ‘moderately harmful’, ‘harmful’, to ‘very harmful’.

Sociodemographic data such as age, sex, ethnicity, year of study, faculty, major, university admission scheme, monthly domestic household income, current residence, and smoking status were collected.

SPSS (Windows version 25; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US) was used for statistical analyses. Medical and non-medical students were compared using independent samples t-test for continuous variables and Chi square test for categorical variables. Multiple linear regression was used to determine significant variables associated with PHQ-9 scores. Multinominal logistic regression was used to determine the effect of such variables on PHQ-9 caseness and AUDIT drinking risk groups.

Results

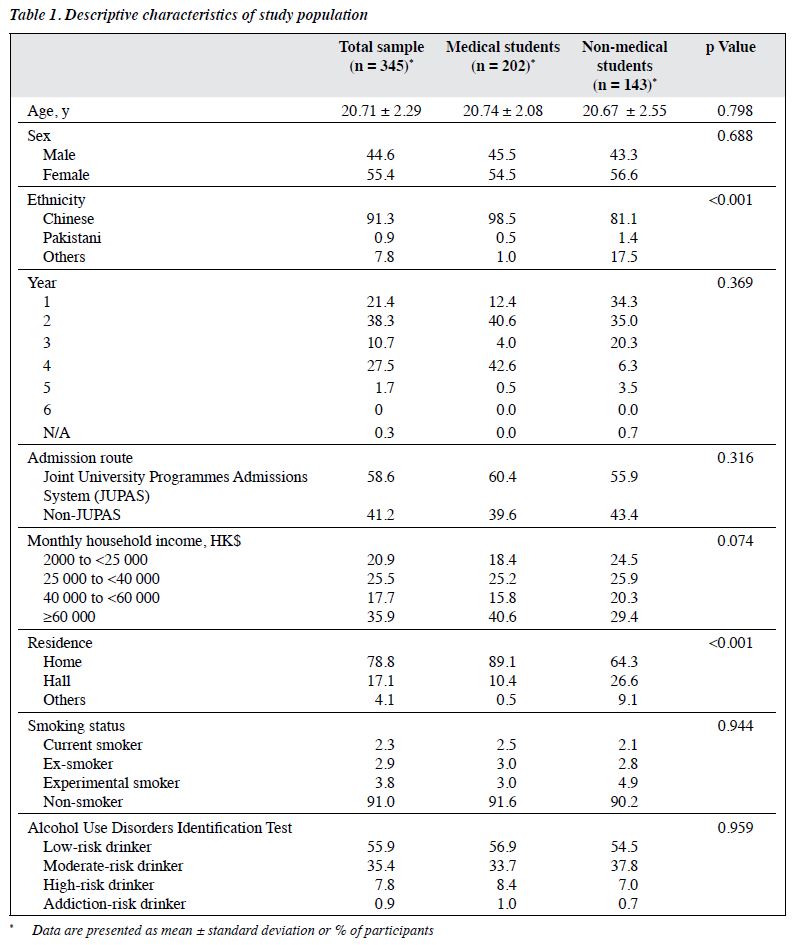

Of 392 respondents, 345 (55.4% female) [mean age, 20.71 ± 2.29 years] were included for analysis (Table 1). 91.3% of them were ethnic Chinese. Based on the AUDIT score, 55.9% were classified as low-risk drinkers, 35.4% as moderate-risk drinkers, 7.8% as high-risk drinkers, 0.9% as addiction-risk drinkers. This contrasted with the self- reported rates of 24.3% as non-drinkers, 52.5% as low- level drinkers, 21.7% as moderate-level drinkers, and 1.5% as high-level drinkers. Based on the CAGE questionnaire, 7.2% were at high suspicion of alcoholism and 0.9% were virtually diagnostic for alcoholism. In addition, 24.1% of respondents consumed alcohol more than twice over the past 2 weeks.

Based on the PHQ-9 score, 44.6%, 11.6%, and 1.7% of respondents had mild, moderate, and moderately severe depressive symptoms, respectively. The prevalence of probable depression was 13.3%. 19.1% reported depression problems or feelings before drinking alcohol, whereas 11.9% experienced depressive symptoms during and after drinking. When drinking, students reported feeling relaxed (67.0%), happy (44.3%), and excited (25.5%), as well as negative emotions including tiredness (13.3%), depression (16.2%), loneliness (6.4%), and anger (2.9%).

49.3% of respondents reported moderate to very high levels of general stress. 60% reported moderate to very high levels of university-related stress.

In multiple linear regression, higher PHQ-9 scores correlated with non-medical faculty students (β = 0.100, p = 0.040), smoking status (β = 0.099, p = 0.033), high levels of general stress (β = 0.282, p < 0.001), high suspicion to virtually diagnostic of alcoholism (β = 0.100, p = 0.040), high to addiction risk of alcohol consumption (β = 0.134, p = 0.006), and stress-coping method of avoidance (β = 0.330, p < 0.001) [Table 2].

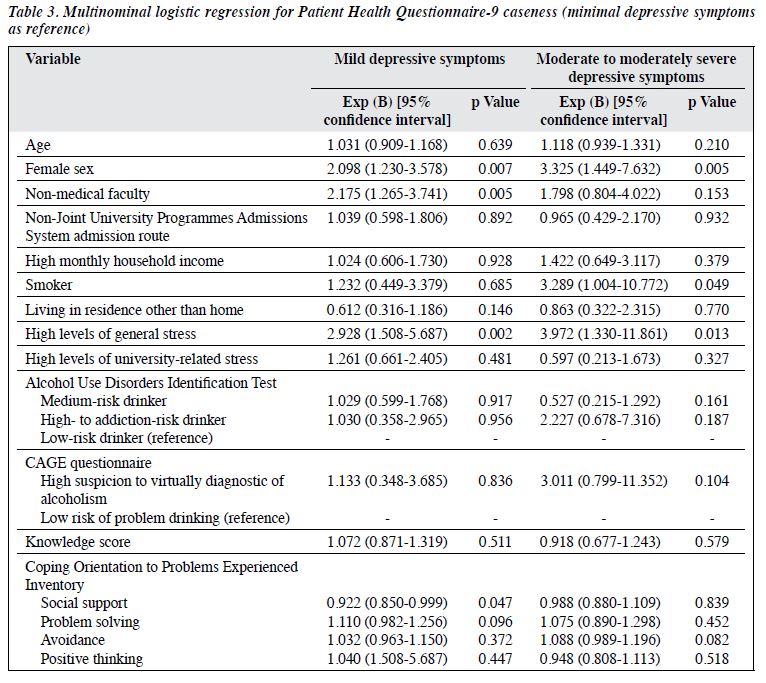

In multinominal logistic regression, using minimal depressive symptoms as the reference, students with mild depressive symptoms were more likely to be female (odds ratio [OR] = 2.098, p = 0.007), non-medical faculty (OR = 2.175, p = 0.005), have high levels of general stress (OR = 2.928, p = 0.002), and less likely to use the stress- coping method of social support (OR = 0.922, p = 0.047) [Table 3]. Students with moderate to severe depressive symptoms were more likely to be female (OR = 3.325, p = 0.005), smokers (OR = 3.289, p = 0.049), and have high levels of general stress (OR = 3.972, p = 0.013) [Table 3].

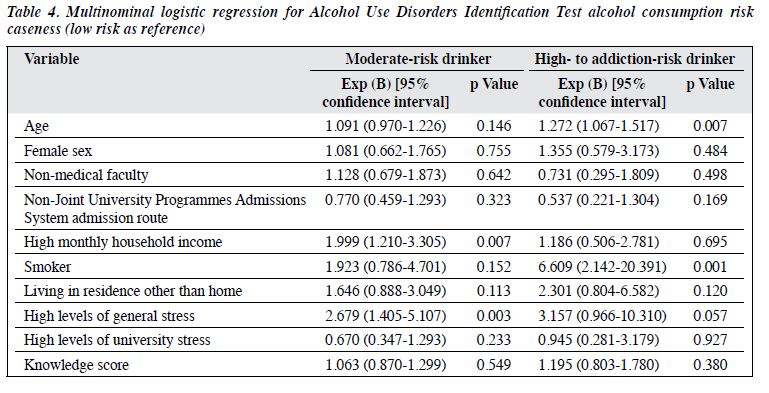

In multinominal logistic regression, using low- risk drinkers (AUDIT scores of 0 to 7) as the reference, moderate-risk drinkers were more likely to have high monthly household income (OR = 1.999, p = 0.007) and high levels of general stress (OR = 2.679, p = 0.003) [Table 4]. High- to addiction-risk drinkers were more likely to be older students (OR = 1.272, p = 0.007) and smokers (OR = 6.609, p = 0.001) [Table 4].

A post-hoc one-way analysis of variance was used to determine differences in stress-coping methods in different levels of alcohol consumption. The score of the coping method of avoidance was significantly higher in high- to addiction-risk drinkers than moderate-risk or low-risk drinkers (19.93 ± 6.05 vs 17.03 ± 4.14 vs 16.37 ± 4.41, p < 0.001). High scores indicate more use of avoidance for stress-coping. In addition, a post-hoc linear regression analysis showed a significant interaction effect of avoidance and stress on PHQ-9 score (β = 0.226, p = 0.003).

Regarding knowledge and perception of drinking on health, 89.5% of students considered alcohol consumption moderately to very harmful to health. 78.0% of students considered alcohol use in their peers as a minor problem or not a problem at all, whereas 56.0% of students considered so for alcohol abuse. 74.2% considered drinking and depression are at least a moderate problem.

Discussion

In the present study, 43.2% of students were moderate- to high-risk drinkers, and 57.9% of students had mild to moderately severe depressive symptoms, which is comparable to the 68.5% reported in another study of Hong Kong university students.13 The prevalence of probable depression was 13.3%, which is lower than the 21% of moderate-to-severe depression reported in Hong Kong university students.51 The differences may be due to the use of different mental health screening scales and our exclusion of those with mental illnesses other than depression and those medically advised not to drink alcohol. Severity of probable depression was associated with high- to addiction- risk drinkers and high suspicion to virtually diagnostic of alcoholism. This finding is consistent with previous studies reporting strong associations between student psychological distress and alcohol consumption.52-54 Depressive symptoms may motivate hazardous drinking behaviour, particularly if students are reluctant to seek professional help for mental health–related issues. However, reverse causality cannot be ruled out owing to our cross-sectional study design.

The was a discrepancy between self-reported drinking status and AUDIT scores. Students underestimated their drinking status, which may result in further hazardous behaviour. 52.1% of respondents considered alcohol consumption harmful or very harmful to health. Further health education to target misconceptions was recommended, as was advice on alcohol intake (setting goals and limits) and referral for counselling and therapy in more severe cases.

Many universities provide structured support such as counselling services to prevent mental health–related issues. However, many students are reluctant to seek help or deny any mental distress. Counselling services reply on self-perception of need, which results in a passive delivering of care and decreased utilisation of mental health services. Thus, it is important to promote accessibility of screening tools for mental health–related issues,55 in order to publicise, demystify, and normalise the help-seeking process via engaging campaigns. In addition, there should be sufficient counsellors and psychologists to fulfil unmet and unrecognised demands. The advisor-advisee and mentor-mentee systems are implemented to identify those with risk,34 but they are highly dependent on students’ comfort and willingness to share personal experiences. As 13.3% of students reported moderate to severe depressive symptoms, teaching institutions should devise context- specific approaches to aid students to improve psychological wellbeing.

Most students considered alcohol use and alcohol abuse among their peers as a minor problem or not a problem at all. Fewer medical students than non-medical students considered alcohol abuse as a serious problem (14.4% vs 20.3%, p = 0.147). This may be because medical students tend to focus on specific risk factors of disease. For instance, hepatocellular carcinoma is mainly associated with hepatitis B and C or liver cirrhosis, lung cancer is mainly associated with smoking, and colorectal cancer is mainly associated with increased red meat intake, longstanding ulcerative colitis, obesity, and genetic factors including familial polyposis coli or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Medical students may consider alcohol consumption a less important risk factor than those specific to the disease. It is crucial to inform correct perception of drinking behaviour to university students, particularly medical students who will provide health advice to the public in future.

Students with higher levels of depressive symptoms were more likely to use avoidance (rather than social support, problem-solving, and positive thinking) for stress- coping. This was consistent with studies that reported increased tendency for avoidant coping in students with higher depressive levels.56,57 Passive coping mechanisms such as avoidance may result in pessimistic thinking, thereby increasing the risk of depression.58,59 Our post hoc analysis confirmed that students who used avoidance to cope with psychological distress were more likely to consume alcohol in managing depressive symptoms. An interaction effect between the use of avoidance coping and stress on depression was observed. Studies with longitudinal design may prove such interrelationships. It is suggested that psychological support should be customised to individual university students based on their coping strategy.

Regarding knowledge of harmful effects of alcohol on health, the least recognised adverse effect of alcohol on health was the increased risk of breast cancer and pancreatitis. Interestingly, medical students were more likely to associate skin cancer with harmful effects of alcohol, but alcohol consumption is not a fully established risk factor for such disease,60 although it is correlated with an increased risk of developing melanoma, especially in body parts protected from sun exposure.61 It is imperative to instil correct knowledge about the risks of excessive alcohol intake on health that may pose detrimental effects on the students.

The prevalence of drinking among university students is rising in Hong Kong. The current policies of zero duty for wine and liquor with an alcoholic content of <30%62 may have exacerbated the problem.

There are limitations to this study. The exclusion criteria (alcohol allergy, long-term disease, mental diseases other than depression, and medical advice not to drink alcohol) may have resulted in underestimation of effect sizes and study results. Our sample was from one university only and may not be representative of all undergraduate students in Hong Kong. However, our sample’s demographics closely concur with those of all tertiary-level students. Students who self-segregated from social contact owing to severe depression, drinking habits, or other reasons are unlikely to be included. Reverse causality and residual confounding cannot be fully excluded owing to the cross- sectional design, as temporal sequences between exposure and outcome cannot be established. Further studies are warranted to delineate relationships between alcohol consumption and depression, as are further longitudinal studies to establish temporal relationships and subgroup variations of correlations identified in this study.

Conclusion

Alcohol consumption and depressive symptoms are prevalent among university students in Hong Kong. The use of avoidance for stress-coping is common in those with higher levels of depressive symptoms and higher-risk drinkers. Students tend to avoid seeking help for depressive symptoms and potentially take up drinking as a coping strategy. Context-specific approaches should be used when providing counselling services for student wellbeing in university settings. Further education of university students on knowledge and perception of alcohol consumption on health should be provided.

Contributors

All authors designed the study. MSCC, SHLP, KLL, and CCYC acquired the data. MSCC, SHLP, and WWTL analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong / Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (reference: HKU/HA HKW IRB UW 18-666). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Ki Yan Chan, Ophelia Chan, Arthur Chang, Sumar Chan, Rachel Lau, and Wai Ching Wong for their assistance with data collection.

References

- Macaskill A. The mental health of university students in the United Kingdom. Br J Guid Counc 2013;41:426-41. Crossref

- Garlow SJ, Rosenberg J, Moore JD, et al. Depression, desperation, and suicidal ideation in college students: results from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention College Screening Project at Emory University. Depress Anxiety 2008;25:482-8. Crossref

- Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, Glazebrook C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J Psychiatr Res 2013;47:391-400. Crossref

- Mall S, Mortier P, Taljaard L, Roos J, Stein DJ, Lochner C. The relationship between childhood adversity, recent stressors, and depression in college students attending a South African university. BMC Psychiatry 2018;18:63. Crossref

- Shim EJ, Noh HL, Yoon J, Mun HS, Hahm BJ. A longitudinal analysis of the relationships among daytime dysfunction, fatigue, and depression in college students. J Am Coll Health 2019;67:51-8. Crossref

- Al-Maashani M, Al-Balushi N, Al-Alawi M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among medical students: a cross- sectional single-centre study. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2020;30:28-31. Crossref

- Jaisoorya TS, Geetha D, Beena KV, Beena M, Ellangovan K, Thennarasu K. Prevalence and correlates of psychological distress in adolescent students from India. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2017;27:56-62.

- Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016;316:2214-36. Crossref

- Tung YJ, Lo KKH, Ho RCM, Tam WSW. Prevalence of depression among nursing students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Today 2018;63:119-29. Crossref

- Cuttilan AN, Sayampanathan AA, Ho RC. Mental health issues amongst medical students in Asia: a systematic review [2000-2015]. Ann Transl Med 2016;4:72.

- Lei XY, Xiao LM, Liu YN, Li YM. Prevalence of depression among Chinese university students: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0153454. Crossref

- World Health Organisation. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva; 2017.

- Lun KW, Chan CK, Ip PK, et al. Depression and anxiety among university students in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2018;24:466-72. Crossref

- Kim JH, Chan KW, Chow JK, et al. University binge drinking patterns and changes in patterns of alcohol consumption among Chinese undergraduates in a Hong Kong university. J Am Coll Health 2009;58:255-65. Crossref

- Abdullah AS, Fielding R, Hedley AJ. Patterns of cigarette smoking, alcohol use and other substance use among Chinese university students in Hong Kong. Am J Addict 2002;11:235-46. Crossref

- Griffiths S, Lau JT, Chow JK, Lee SS, Kan PY, Lee S. Alcohol use among entrants to a Hong Kong university. Alcohol Alcohol 2006;41:560-5. Crossref

- Karam E, Kypri K, Salamoun M. Alcohol use among college students: an international perspective. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2007;20:213-21. Crossref

- Nourse R, Adamshick P, Stoltzfus J. College binge drinking and its association with depression and anxiety: a prospective observational study. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2017;27:18-25.

- Haynes JC, Farrell M, Singleton N, et al. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for anxiety and depression: results from the longitudinal follow- up of the National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Br J Psychiatry 2005;187:544-51. Crossref

- Mushquash AR, Stewart SH, Sherry SB, Sherry DL, Mushquash CJ, Mackinnon AL. Depressive symptoms are a vulnerability factor for heavy episodic drinking: a short-term, four-wave longitudinal study of undergraduate women. Addict Behav 2013;38:2180-6. Crossref

- Martinez P, Neupane SP, Perlestenbakken B, Toutoungi C, Bramness JG. The association between alcohol use and depressive symptoms across socioeconomic status among 40- and 45-year-old Norwegian adults. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1146. Crossref

- Johannessen EL, Andersson HW, Bjørngaard JH, Pape K. Anxiety and depression symptoms and alcohol use among adolescents: a cross sectional study of Norwegian secondary school students. BMC Public Health 2017;17:494. Crossref

- Cobiac L, Wilson N. Alcohol and mental health: a review of evidence, with a particular focus on New Zealand. Burden of Disease Epidemiology, Equity and Cost-Effectiveness Programme (BODE3), Department of Public Health, University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand; 2018.

- Lam LC, Wong CS, Wang MJ, et al. Prevalence, psychosocial correlates and service utilization of depressive and anxiety disorders in Hong Kong: the Hong Kong Mental Morbidity Survey (HKMMS). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015;50:1379-88. Crossref

- Cheung T, Yip PS. Depression, anxiety and symptoms of stress among Hong Kong nurses: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:11072-100. Crossref

- Peltzer K. Depressive symptoms in relation to alcohol and tobacco use in South African university students. Psychol Rep 2003;92:1097-8. Crossref

- Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Aloba OO, Mapayi BM, Oginni OO. Depression amongst Nigerian university students. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006;41:674-8. Crossref

- Gonzalez VM, Reynolds B, Skewes MC. Role of impulsivity in the relationship between depression and alcohol problems among emerging adult college drinkers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2011;19:303-13. Crossref

- Scheier MF, Weintraub JK, Carver CS. Coping with stress: divergent strategies of optimists and pessimists. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;51:1257-64. Crossref

- Brougham RR, Zail CM, Mendoza CM, Miller J. Stress, sex differences, and coping strategies among college students. Curr Psychol 2009;28:85-97. Crossref

- Kloep M, Hendry LB, Ingebrigtsen JE, Glendinning A, Espnes GA. Young people in `drinking’ societies? Norwegian, Scottish and Swedish adolescents’ perceptions of alcohol use. Health Educ Res 2001;16:279-91. Crossref

- Fischbein R, Bonfine N. Pharmacy and medical students’ mental health symptoms, experiences, attitudes and help-seeking behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ 2019;83:7558. Crossref

- Ciarrochi JV, Deane FP. Emotional competence and willingness to seek help from professional and nonprofessional sources. Br J Guid Counc 2001;29:233-46. Crossref

- Chew-Graham CA, Rogers A, Yassin N. ‘I wouldn’t want it on my CV or their records’: medical students’ experiences of help-seeking for mental health problems. Med Educ 2003;37:873-80. Crossref

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. Alcohol and Depression 2019. Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/problems-disorders/alcohol-and-depression.

- Tuisku V, Pelkonen M, Kiviruusu O, Karlsson L, Marttunen M. Alcohol use and psychiatric comorbid disorders predict deliberate self-harm behaviour and other suicidality among depressed adolescent outpatients in 1-year follow-up. Nord J Psychiatry 2012;66:268-75. Crossref

- Ralston TE, Palfai TP. Depressive symptoms and the implicit evaluation of alcohol: the moderating role of coping motives. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012;122:149-51. Crossref

- Kenney SR, Anderson BJ, Stein MD. Drinking to cope mediates the relationship between depression and alcohol risk: different pathways for college and non-college young adults. Addict Behav 2018;80:116-23. Crossref

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction 1993;88:791-804. Crossref

- Yip BHK, Chung RY, Chung VCH, et al. Is Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) or its shorter versions more useful to identify risky drinkers in a Chinese population? A diagnostic study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0117721. Crossref

- Leung SF, Arthur D. The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): validation of an instrument for enhancing nursing practice in Hong Kong. Int J Nurs Stud 2000;37:57-64. Crossref

- Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA 1984;252:1905-7. Crossref

- Stock C, Mikolajczyk R, Bloomfield K, et al. Alcohol consumption and attitudes towards banning alcohol sales on campus among European university students. Public Health 2009;123:122-9. Crossref

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606-102. Crossref

- Yu X, Tam WW, Wong PT, Lam TH, Stewart SM. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for measuring depressive symptoms among the general population in Hong Kong. Compr Psychiatry 2012;53:95-102. Crossref

- Du N, Yu K, Ye Y, Chen S. Validity study of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items for Internet screening in depression among Chinese university students. Asia Pac Psychiatry 2017;9:10.1111/ appy.12266. Crossref

- Wang W, Bian Q, Zhao Y, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2014;36:539-44. Crossref

- Baumstarck K, Alessandrini M, Hamidou Z, Auquier P, Leroy T, Boyer L. Assessment of coping: a new French four-factor structure of the brief COPE inventory. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15:8. Crossref

- Greenaway K, Louis W, Parker S, Kalokerinos E, Smith J, Terry D. Measures of coping for psychological well-being. 2015:322-51. Crossref

- Meyer B. Coping with severe mental illness: relations of the brief COPE with symptoms, functioning, and well-being. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2001;23:265-77. Crossref

- Leung CH. University support, adjustment, and mental health in tertiary education students in Hong Kong. Asia Pacific Educ Rev 2017;18:115-22. Crossref

- Tembo C, Burns S, Kalembo F. The association between levels of alcohol consumption and mental health problems and academic performance among young university students. PLoS One 2017;12:e0178142. Crossref

- Sæther SMM, Knapstad M, Askeland KG, Skogen JC. Alcohol consumption, life satisfaction and mental health among Norwegian college and university students. Addict Behav Rep 2019;10:100216. Crossref

- Ferreira VR, Jardim TV, Sousa ALL, Rosa BMC, Jardim PCV. Smoking, alcohol consumption and mental health: data from the Brazilian study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents (ERICA). Addict Behav Rep 2019;9:100147. Crossref

- Rosenthal B, Wilson W. Mental health services: use and disparity among diverse college students. J Am Coll Health 2008;57:61-8. Crossref

- Sawhney M, Kunen S, Gupta A. Depressive symptoms and coping strategies among Indian university students. Psychol Rep 2020;123:266-80. Crossref

- Sadaghiani NSK, Sorkhab MS. The comparison of coping styles in depressed, anxious, under stress individuals and the normal ones. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2013;84:615-20. Crossref

- Dyson R, Renk K. Freshmen adaptation to university life: depressive symptoms, stress, and coping. J Clin Psychol 2006;62:1231-44. Crossref

- Chou PC, Chao YMY, Yang HJ, Yeh GL, Lee TSH. Relationships between stress, coping and depressive symptoms among overseas university preparatory Chinese students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2011;11:352. Crossref

- Shield KD, Parry C, Rehm J. Chronic diseases and conditions related to alcohol use. Alcohol Res 2013;35:155-73.

- Rivera A, Nan H, Li T, Qureshi A, Cho E. Alcohol intake and risk of incident melanoma: a pooled analysis of three prospective studies in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2016;25:1550-8. Crossref

- HKSAR Government. Alcohol and Health: Hong Kong Situation; Available from: https://www.dh.gov.hk/pub_rec/pdf/ncd_ap2