East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2021;31:105-11 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2018

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Shahrbanoo Ghahari, Department of Mental Health, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Fatemeh Veisy, Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Mohammad Kazem Atef Vahid, Department of Clinical Psychology and Department of Health Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Mehran Zarghami, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

Address for correspondence: Fatemeh Veisy, Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Email: veisy.fateme@gmail.com

Submitted: 12 March 2020; Accepted: 24 November 2021

Abstract

Objectives: To assess the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the short Schema Mode Inventory (SMI).

Methods: The short SMI was translated into Persian by three clinical psychology professors and then back-translated into English by two professors in English language. Between 2017 and 2018, patients from Iran Psychiatric Hospital and Rasoul Akram Hospital who were diagnosed with personality disorder in Axis II by a psychiatrist and had minimum education of middle school were included. Controls included students and staff of the Iran Medical Sciences University who had minimum education of middle school. All participants were asked to complete the short SMI and the Young Schema Questionnaire – Short Form (YSQ-SF). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha), test-retest reliability, confirmatory factor analysis, internal correlation of schema mode subscales, and correlation between short SMI and YSQ-SF were assessed.

Results: Of 406 participants, 205 (50.7%) were patients and 201 (49.3%) were controls. The fitness indices indicated that the 14-factor model was reliable, with χ2 = 12917.97, p < 0.001, df = 5795, χ2/df = 2.23, CFI = 0.96, NNFI = 0.96 SRMR = 0.08, and RMSEA = 0.05. The internal consistency of the short SMI was satisfactory (M = 0.94). Among 34 participants in the control group who completed the short SMI again after 2 weeks, test-retest reliability was high (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.88, p < 0.001). The short SMI and YSQ-SF correlated strongly in terms of the overall scale and most subscales. The patient and control groups differed significantly in most subscales.

Conclusions: Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the short SMI showed good validity and reliability. It can be used in clinical and research settings.

Key words: Reproducibility of results; Schema therapy; Validation study

Introduction

Unsatisfied basic childhood needs may result in negative and dysfunctional cognitive structures and development of early maladaptive schema and thus may affect the entire life of an individual.1 Schema therapy has been used for patients with personality disorders and those who are resistant to change.2,3 There are three basic concepts in schema therapy: early maladaptive schema, coping style, and schema mode.1

Coping styles are strategies (overcompensation, avoidance, and surrender) that individuals adopt to preserve their maladaptive schemas.4 The matching of schemas and coping styles is known as schema modes,5 which are activated at any given moment and represent moment-to-moment changes of emotional, cognitive, and coping responses. After being triggered by emotional events, schema modes rapidly change the mood of patients with personality disorders and thus their behaviour and emotion.2 The schema modes cover both healthy and pathologic aspects on both specific and broad subjects.1

Dysfunctional schema modes may activate unpleasant emotions, avoidance responses, and self-destructive behaviours.1 There are four categories: (1) inefficient child modes, which arise from inadequate satisfaction with basic needs, particularly the attachment need; (2) inefficient adult modes, which are due to high standards and self-assessments originating from maladaptive responses of parents leading to dogmatic self-beliefs; (3) inefficient coping modes, which are the extreme use of the three coping styles to reduce the emotional pain of the previous two modes; and (4) healthy adult mode, which helps solve problems, develop healthy relationships, and deal with stressors and emotions.6 A specific schema mode is found in each personality disorder, as a specific group of mindsets are often active in each personality disorder.1,7-10

Schema therapy is more effective than transition-based psychotherapy in reducing dysfunction in patients with borderline personality disorder.11,12 It is also more effective than usual treatments in managing personality disorders.13 It results in a lower risk of recommitting a crime and a higher likelihood of returning to society among forensic patients.14

The short Schema Mode Inventory (SMI) is based on the original 124-item questionnaire and is used to assess the active schema modes of patients. The short SMI has been validated and applied in clinical and research situations.15 It enables therapists to assess the active schema modes of patients at any given moment.16 Psychometric properties of the short SMI have been validated in different countries.16-19 The Italian version confirmed its factor structure in patients with axis I and II disorders.16 The German version comprises 14 factors and has been validated for patients and healthy controls to be consistent with the SMI.17 The Pakistani version included cross-language validation.18 The Greek version was validated in non-patients, outpatients, and inpatients.19 The present study aimed to investigate the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the short SMI.

Methods

The short SMI was translated into Persian by three clinical psychology professors and then back-translated into English by two professors in English language. The back- translated version was compared with the original version, and necessary corrections were made.

Between 2017 and 2018, patients from Iran Psychiatric Hospital and Rasoul Akram Hospital who were diagnosed with personality disorder in Axis II by a psychiatrist and had minimum education of middle school were included. Those with psychotic disorders including schizophrenia or schizoaffective and mood disorders with psychotic characteristics were excluded. Controls included students and staff of the Iran Medical Sciences University who had minimum education of middle school. Controls were evaluated by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders. Those with personality disorder in Axis II were excluded. Informed consent was obtained from each participant. All participants were asked to complete the short SMI and the Young Schema Questionnaire – Short Form (YSQ-SF).

The short SMI comprises 118 items for 14 schema modes: vulnerable child, angry child, enraged child, impulsive child, undisciplined child, happy child, compliant surrender, detached protector, detached self- soother, self-aggrandiser, bully and attack, punitive parent, demanding parent, and healthy adult. Each schema mode was assessed by four to ten items. Each item is rated in a six-point Likert scale from never to always; higher scores indicate manifestation of the relevant schema mode. The internal consistency of items is 0.79 to 0.96. The test-retest reliability of short SMI is appropriate, and the construct validity is average.15

The YSQ-SF comprises 75 items for 15 schemas: emotional deprivation, abandonment, mistrust/abuse, social isolation, defectiveness/shame, failure, dependence/ incompetence, vulnerability to harm and illness, enmeshment, subjugation, self-sacrifice, emotional inhibition, unrelenting standards, entitlement, and insufficient self-control/self- discipline.20 Each schema is assessed by five items; each item is rated in a six-point Likert scale from completely false to completely true. Its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 94.4 in a non-clinical sample in Iran.21

Variables comprised latent and observable variables. Latent variables were the constructs or factors that are not directly visible (the 14 schema modes of the short SMI) and were derived from observable variables (the 118 items of the short SMI). Normality (skewness and kurtosis) of the observable variables was assessed. Construct validity of the short SMI was verified using the confirmatory factor analysis.

Model parameters were estimated using the maximum likelihood method. Owing to the high collinearity between the observable variables, point estimation was used to resolve the positive data uncertainty. However, using point estimation or not resulted in a difference in data fitness and standard errors (but not so in ordinal scales). As data were not ordinal, the maximum likelihood method with point estimation was used.

A combination of three to four indicators was used for structural equation modelling. The Chi square to degree of freedom (χ2/df) ratio and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were selected among absolute fitness indices, whereas the Bentler and Bonett non-normal fitness index (NNFI), the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR), and the comparative fitness index (CFI) were selected among comparative fitness indices.

Internal consistency was assessed using the Cronbach’s alpha, and test-retest reliability was assessed in 34 participants in the control group after a 2-week interval.

The convergent validity was determined by the correlation between the two questionnaires. Partial correlation method was used to control the differences in variables. Participants with missing data were excluded. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

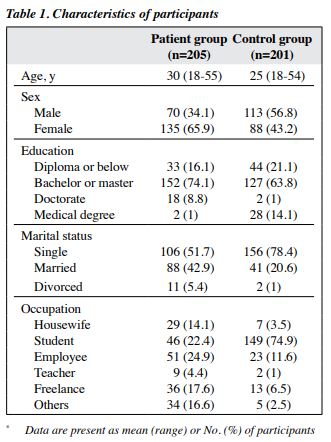

Of 406 participants, 205 (50.7%) were patients and 201 (49.3%) were controls (Table 1). The diagnoses of patients included borderline personality disorder (18%), paranoid personality disorder (8.3%), antisocial personality disorder (7.8%), dependent personality disorder (16.1%), narcissistic personality disorder (9.8%), obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (29.8%), histrionic personality disorder (4.4%), passive-aggressive personality disorder (0.5%), schizoid-schizotypal personality disorder (1.5%), and multiple personality disorders (3.9%).

Four of 118 observable variables (items 4, 5, 24, and 94) were excluded because their skewness was >2 when their kurtosis was >3. The construct validity of the remaining 114 items had a score >0.3, except for items 21, 27, 61, 89, and 104. Thus, the 14-factor model with 109 observable variables was confirmed. All subscales had normal skewness and kurtosis rates, with healthy adult having the highest mean (38.78) and undisciplined child having the lowest mean (8.93).

The fitness indices indicated that the 14-factor model was reliable, with χ2=12917.97, p<0.001, df=5795, χ2/df=2.23, CFI=0.96, NNFI=0.96 SRMR=0.08, and RMSEA=0.05.

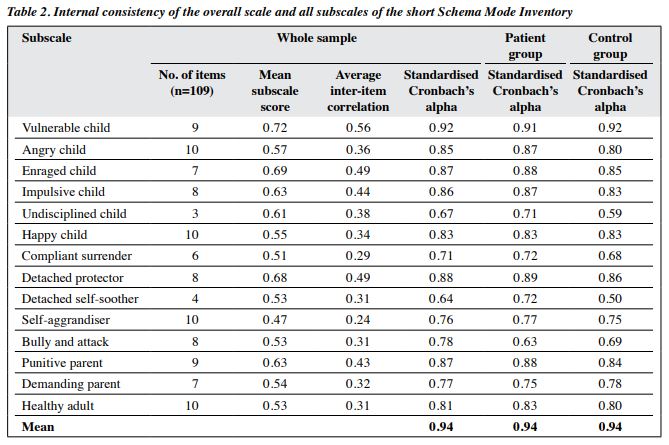

Path coefficients of the remaining 109 items of the 14-factor short SMI were appropriate (range, 0.31-0.80; mean, 0.58; Table 2). The mean subscale scores ranged from 0.47 to 0.72, which indicated appropriate level of explanation of latent variables by observable variables.

Internal consistency of the overall scale and all subscales was good, except for undisciplined child (0.67) and detached self-soother (0.64). However, the number of items for these two subscales was smaller, as was their Cronbach’s alpha. Therefore, attention should be paid to their average inter-item correlations, which were 0.38 and 0.31, respectively. The average inter-item correlation of 0.2 to 0.4 was considered acceptable.22

Among 34 participants in the control group who completed the short SMI again after 2 weeks, test-retest reliability was high (Pearson correlation coefficient=0.88, p<0.001).

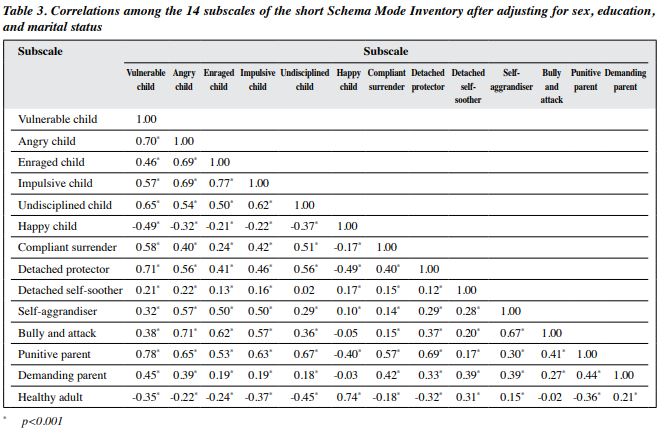

Correlation was significant among the 14 subscales, except for between undisciplined child and detached self- soother subscales, between happy child and bully and attack subscales, between happy child and demanding parent subscales, and between bully and attack and healthy adult subscales (Table 3). In addition, happy child and healthy adult subscales had a negative correlation with most subscales.

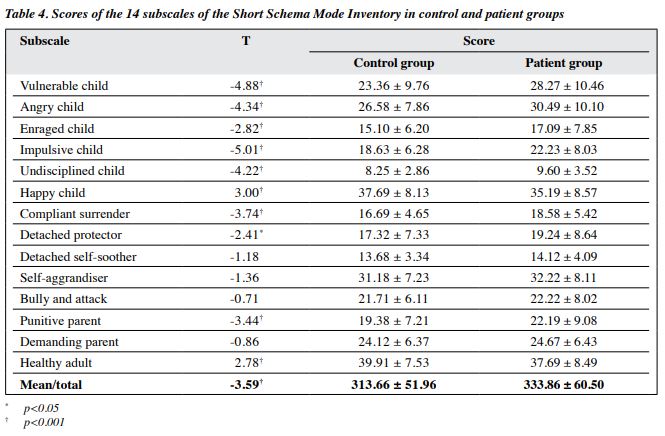

The control and patient groups differed significantly in all subscale scores, except for detached self-soother, self-aggrandiser, bully and attack, and demanding parent subscales (Table 4). Scores were higher in the patient group than in the control group for all subscales, except for happy child and healthy adult subscales.

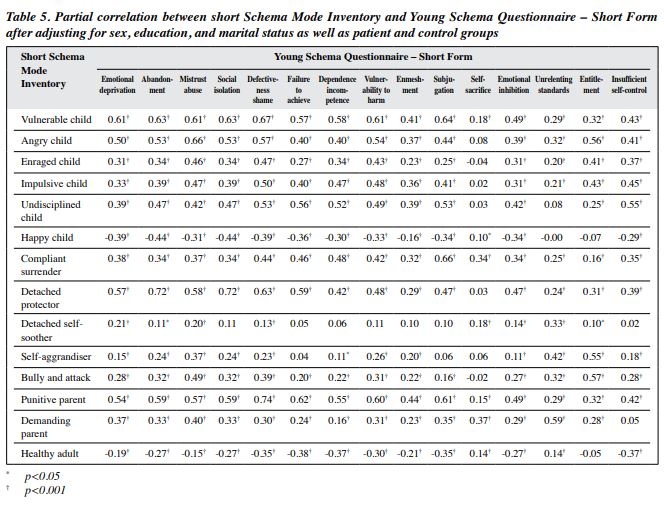

The short SMI and YSQ-SF correlated strongly in terms of the overall scale and most subscales, except for between the detached self-soother subscale of short SMI and some subscales of YSQ-SF and between the self- sacrifice subscale of YSQ-SF and some subscales of short SMI (Table 5).

Discussion

The present study confirmed the validity of the 14-factor model of the short SMI. Internal consistency of items was satisfactory. Fitness indices showed a good validity. Different schema modes can be distinguished. The finding of the present study is consistent with that of previous studies.15-17

None of the correlations between subscales were 1. Therefore, there are differences between various schema modes and their structures. Of the four pairs that were not correlated, three were related to the correlation between effective and ineffective schema modes, which is similar to that reported in the Italian study.16

Internal consistency of the short SMI was appropriate, with undisciplined child and detached self-soother subscales slightly lower than other subscales. This finding is consistent with that in a study.18

The control and patient groups differed significantly in most subscales. In general, scores were lower in patients than in controls for inefficient schema modes but higher for efficient schema modes. This finding is in line with that in previous studies.15-17,19 In our study, there was no significant difference between patients and controls in terms of detached self-soother, self-aggrandiser, bully and attack, and demanding parent subscales. In the German version of short SMI, there was no significant difference in the self- aggrandiser subscale between the control group, psychiatric patients, and forensic patients.17

All schemas of the YSQ-SF had a negative correlation with the healthy adult mode of short SMI, except for between this mode and the unrelenting standards schema, which was a positive correlation, and between this mode and the entitlement schema, which was a negative but not significant correlation. This finding is not in line with that in a previous study.19 The discrepancy may be because 73% and 85% of participants in patient and control groups, respectively, have college education, which may be associated with unrealistic standard.

The correlation between happy child mode of short SMI and all maladaptive schemas of YSQ-SF was negative, except for self-sacrifice schema. All correlations of this mode with the early maladaptive schemas were significant, except for unrelenting standards and entitlement schemas. This finding is not in line with that in a previous study.19 The correlation of self-sacrifice schema of YSQ-SF with other modes of short SMI was less significant than with other maladaptive schemas of YSQ-SF. This may be because the positive correlation between happy child mode of short SMI and self-sacrifice schema of YSQ-SF is due to high education level of participants and high standard and attitude to their job leading to prioritising others.

The schema mode model provides a clear structure for conceptualisation of growth for every individual. Some schema modes are more prominent in each personality disorder, and there are specific goals for each schema mode that can affect the treatment road map.6 Therefore, our evaluation of schema modes has important clinical implications, because each schema mode can be targeted and corrected through intervention when identified.4 We confirmed that the Persian version of the 109-item 14-factor short SMI is reliable and valid.

There are several limitations to the present study. The number of items was large, which include 118 items in the short SMI and 75 items in the YSQ-SF. This prolonged the response time and had a negative impact on patients in particular. The controls were not assessed for Axis I disorders, and these disorders can affect maladaptive schemas. In addition, its potential confounding effects were not controlled. Furthermore, missing data were excluded; it may have been better if advanced analysis of missing data had been performed. Test-retest reliability was performed in a small sample of control group, which limits the reliability of the results. Further studies with larger samples of patients with Axis I, Axis II, and forensic disorders are warranted.

Conclusion

Psychometric properties of the Persian version of short SMI showed good validity and reliability. It can be used in clinical and research settings.

Contributors

All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflict of Interest

Authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support

This study was supported by the Iran University Medical of Science (29276).

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (reference: IR.IUMS.REC 1395.95-03-185-29276). The authors abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct set out by the American Psychological Association.

References

- Young JE, Klosko JS, Weishaar ME. Schema therapy: a Practitioner’s Guide. New York: Guilford Press; 2003.

- Lobbestael J, van Vreeswijk M, Arntz A. Shedding light on schema modes: a clarification of the mode concept and its current research status. Netherlands J Psychol 2007;63:69-78. Crossref

- Arntz A. Do personality disorders exist? On the validity of the concept and its cognitive-behavioral formulation and treatment. Behav Res Ther 1999;37:S97-S134. Crossref

- Lobbestael J. Lost in fragmentation. Schema modes, childhood trauma, and anger in borderline and antisocial personality disorder. Doctoral dissertation. Maastricht: Datawyse / Universitaire Pers Maastricht; 2008. Available at: https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20080612jl. Crossref

- Bamber M. The good, the bad and defenceless. Jimmy-a single case study of schema mode therapy. Clin Psychol Psychother 2004;11:425-38. Crossref

- Fassbinder E, Schweiger U, Jacob G, Arntz A. The schema mode model for personality disorders. Die Psychiatrie 2014;11:78-86. Crossref

- Bamelis LL, Renner F, Heidkamp D, Arntz A. Extended schema mode conceptualizations for specific personality disorders: an empirical study. J Personality Dis 2011;25:41-58. Crossref

- Lobbestael J, Van Vreeswijk MF, Arntz A. An empirical test of schema mode conceptualizations in personality disorders. Behav Res Ther 2008;46:854-60. [repeat ref 4] Crossref

- Johnston C, Dorahy MJ, Courtney D, Bayles T, O’Kane M. Dysfunctional schema modes, childhood trauma and dissociation in borderline personality disorder. J Behav Ther Experimental Psychiatry 2009;40:248-55. Crossref

- Van Vreeswijk M, Broersen J, Nadort M. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Schema Therapy: Theory, Research, and Practice. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2015.

- Giesen-Bloo J, Van Dyck R, Spinhoven P, et al. Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: randomized trial of schema-focused therapy vs transference-focused psychotherapy. Arch General Psychiatry 2006;63:649-58. Crossref

- Sempertegui GA, Karreman A, Arntz A, Bekker MH. Schema therapy for borderline personality disorder: a comprehensive review of its empirical foundations, effectiveness and implementation possibilities. Clin Psychol Rev 2013;33:426-47. Crossref

- Bamelis LL, Evers SM, Spinhoven P, Arntz A. Results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness of schema therapy for personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2014;171:305-22. Crossref

- Bernstein DP, Nijman HL, Karos K, Keulen-de Vos M, de Vogel V, Lucker TP. Schema therapy for forensic patients with personality disorders: design and preliminary findings of a multicenter randomized clinical trial in the Netherlands. Int J Forensic Mental Health 2012;11:312-24. Crossref

- Lobbestael J, van Vreeswijk M, Spinhoven P, Schouten E, Arntz A. Reliability and validity of the short Schema Mode Inventory (SMI). Behav Cogn Psychother 2010;38:437-58. Crossref

- Panzeri M, Carmelita A, De Bernardis E, Ronconi L, Dadomo H. Factor structure of the Italian short Schema mode Inventory (SMI). Int J Humanit Soc Sci 2016;6:43-55.

- Reiss N, Dominiak P, Harris D, Knörnschild C, Schouten E, Jacob GA. Reliability and validity of the German version of the Schema Mode Inventory. Eur J Psychol Assess 2012;28:297-304. Crossref

- Riaz MN, Khalily T, Kalsoom UE. Translation, adaptation, and cross language validation of short Schema Mode Inventory (SMI). Pakistan J Psychol Res 2013;28:51-64.

- Lyrakos DG. The validity of Young Schema Questionnaire 3rd version and the Schema Mode Inventory 2nd version on the Greek population. Psychology 2014;5:461-77. Crossref

- Schmidt NB, Joiner TE, Young JE, Telch MJ. The schema questionnaire: Investigation of psychometric properties and the hierarchical structure of a measure of maladaptive schemas. Cogn Ther Res 1995;19:295-321. Crossref

- Sadooghi Z, Aguilar-Vafaie ME, Rasoulzadeh Tabatabaie K, Esfehanian N. Factor analysis of the young schema questionnaire-short form in a nonclinical Iranian sample [in Persian]. Iranian J Psychiatry Clin Psychol 2008;14:214-9.

- Cox T, Ferguson E. Measurement of the subjective work environment. Work Stress 1994;8:98-109. Crossref