East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2022;32:17-21 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2205

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

MH Chan, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Allen TC Lee, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Address for correspondence: Dr Allen Lee, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, G/F, Multi-Centre, Tai Po Hospital, Hong Kong SAR. Email: allenlee@cuhk.edu.hk

Submitted: 17 January 2022; Accepted: 28 February 2022

Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to determine the prevalence of depression and the level of perceived social support among occupational therapists during the pandemic, and to identify any associations between depression and perceived social support.

Methods: Using convenience and snowball sampling, occupational therapists aged ≥18 years who were working in Hong Kong and able to read and understand Chinese were invited to participate in a survey between January 2021 and April 2021 (during the fourth wave of COVID-19 pandemic). Data collected included age, sex, education level, employment status, marital status, living status, level of perceived social support (measured by the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [MSPSS-C]) and level of depression (measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9]).

Results:

87 occupational therapists completed the survey. The mean MSPSS-C score was 67.87; 88.5% of participants had a high level of perceived social support. The mean PHQ-9 score was 4.67; 59.8% of participants had no or minimal depression and 11.5% of participants had clinical depression. The MSPSS-C score negatively correlated with the PHQ-9 score (rs = -0.401, p < 0.001). In regression analysis, the MSPSS-C score was associated with the PHQ-9 score (F(1, 85) = 44.846, r = 0.588, p < 0.001). About 34.5% of the variance of the PHQ-9 score was accounted for by the MSPSS-C score.

Conclusion: Higher level of perceived social support is associated with lower level of depression. Social support might serve as a protective factor for depression among occupational therapists in Hong Kong during the pandemic.

Key words: COVID-19; Depression; Occupational therapists; Social Support

Introduction

COVID-19 is a major threat to public health worldwide.1,2 Healthcare workers (medical doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals) are at risk of developing adverse mental health outcomes, owing to the risk of infection at work, worries of transmission to family members at home, shortage of personal protective equipment, and longer working hours and heavier workload during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare workers have a high level of stress and symptoms of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic.3-8 Timely identification and management are crucial in maintaining their quality of life and functioning, minimising long-term psychological sequalae, sustaining the healthcare services, and preventing the collapse of the healthcare system.

Social support contains four components: emotional support, instrumental support, informational support, and appraisal support.9 It can be provided by partners, relatives, friends, or other people.10 Social support improves mental status possibly in the form of benefits from social relationships and a buffer against stressful situations.11 Low level of social support is associated with the occurrence of depression symptoms when exposed to stress.12,13 Social support may be a potential determinant for depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. As COVID-19 is highly infectious and its manifestation is relatively non-specific and even asymptomatic,14 many healthcare workers have concerns about infecting their friends and family members15 and thus opt to reduce contact with others or even move out of their home. This may have a negative impact on gaining social support. Furthermore, public health measures such as social distancing and quarantine may further disrupt the social routine and interaction, leading to a reduction in social support.

Duties of occupational therapists include assessment and implementation of rehabilitative activities or programmes and outreach services and community visits for environmental modification and community integration. These duties might increase the risk of COVID-19 infection and adversely affect mental health.

Various studies of mental status or perceived support during the COVID-19 pandemic focus on doctors and nurses.3-8 This study aimed to determine the prevalence of depression and the level of perceived social support among occupational therapists during the pandemic, and to identify any associations between depression and perceived social support. We hypothesised that higher level of perceived social support was associated with lower level of depression among occupational therapists during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This cross-sectional observational study was approved by the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (Reference: SBRE-20-301). Informed consent was obtained from each participant. According to the 2017 Health Manpower Survey of Department of Health,16 a total of 1908 occupational therapists from public hospitals, non-government organisations, and private settings were registered in Hong Kong. Using convenience and snowball sampling, occupational therapists aged ≥18 years who were working in Hong Kong and able to read and understand Chinese were invited to participate in a survey between January 2021 and April 2021 (during the fourth wave of COVID-19 pandemic).

Participants were interviewed face-to-face by a researcher. Data collected included age, sex, education level, employment status, marital status, living status, level of perceived social support, and level of depression. The duration of the interview was 10 to 15 minutes.

Perceived social support (emotional support, comfort, and assistance in making decisions) was measured using the validated Chinese version of the 12-item self-rated Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS-C).17 There are three subscales for perceived social support from family, friends, and significant others. Each subscale involves four items. Each item was rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree).18 Total scores range from 12 to 84; higher scores indicate higher perceived social support.

Depression was measured using the validated Chinese version of the 9-item self-report Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),19 which is derived from the Patient Health Questionnaire20 based on the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for depression. According to the frequency of each symptom over the previous 2 weeks, each item is rated from 0 to 3 (0 for not at all, 1 for several days, 2 for more than half the days, and 3 for nearly every day). Total scores range from 0 to 27 (0-4 for none or minimal depression, 5-9 for mild depression, 10-14 for moderate depression, 15-19 for moderately severe depression, and for 20-27 severe depression). A score of ≥10 was defined as clinical depression.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (Windows version 26; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US). Spearman’s rho was used to assess the correlation between the level of depression and the level of perceived social support. Regression analysis was conducted to determine significant factors for PHQ-9 score after adjusting for potential confounding factors. All covariates were selected a priori. All tests were two-tailed. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

87 (29 male and 58 female) occupational therapists aged 21 to 41 years completed the survey (Table 1). Most were aged <30 years (89.7%), single (89.7%), working in public hospitals (86.2%), and living with family (95.4%). The mean MSPSS-C score was 67.87 (range, 20-82); 88.5% of participants had a high level of perceived social support. The mean PHQ-9 score was 4.67 (range, 0-24); 59.8% of participants had no or minimal depression and 11.5% of participants had clinical depression.

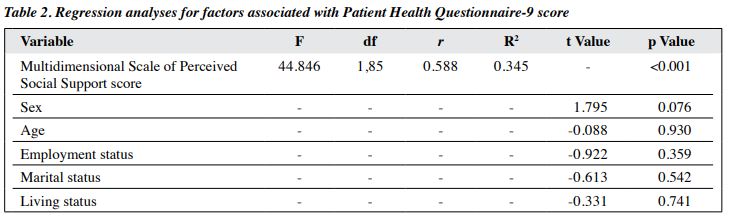

The MSPSS-C score negatively correlated with the PHQ-9 score (rs = -0.401, p <0.001). In regression analysis, the MSPSS-C score was associated with the PHQ-9 score (F(1, 85) = 44.846, r = 0.588, p < 0.001, Table 2). About 34.5% of the variance of the PHQ-9 score was accounted for by the MSPSS-C score. None of the demographic factors was associated with the PHQ-9 score.

Discussion

In our cohort of occupational therapists, the perceived social support was relatively high despite the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and depression was not as prevalent as that in studies of other healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic.3-8 In addition, lower levels of depression correlated with higher levels of perceived social support.

One explanation for the relatively high perceived social support, particularly from friends and partners, was that friends might show more care and warm regards to each other during the pandemic. During the latter phase of the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong, more family and social support were cultivated among local residents, as people treasured families and friendships more during public health crisis.21 Support for frontline healthcare professionals might have been more during the pandemic. In a Dutch population during the COVID-19 pandemic, more meaningful social connection and increased sense of social connectedness were reported.22 As most of our participants were living with their family members and relatively young, they might have more family support and have less difficulty in using digital communications to maintain social connectedness with their friends and partners during the pandemic.

Public health emergency often leads to adverse mental health outcomes in the general population23-26 and healthcare professionals.3-8 However, in the present study, occupational therapists reported fewer mood symptoms and had a lower prevalence of clinical depression than other healthcare professionals and the general population. One explanation was the difference in the timing of sampling. The previous studies were conducted at the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020. As COVID-19 was a novel disease, it might cause more psychosocial disturbances than other infectious diseases.27 The present study was conducted during the fourth wave of the pandemic; healthcare workers might have more knowledge and experience about COVID- 19 and therefore responded more appropriately. Another explanation was the relatively sufficient supply of personal protective equipment. One of the strongest risk factors for depression in healthcare workers was the insufficient supply of personal protective equipment such as face masks.4 At the early stage of COVID-19 outbreak, the demand for personal protective equipment sharply increased and resulted in shortages. With a stable supply of personal protective equipment, the level of depression might be mitigated at the time of our study.

In the present study, higher level of perceived social support was associated with less depressive symptoms among occupational therapists during the pandemic. Good social support might serve as a protective factor for poor mental health in the pandemic.28-31 Adequate social support has a positive effect on the psychological health by improving self-efficacy and reducing stress.32 However, social support is a multidimensional construct affected by personal values, socialisation process, and politico- social environment of an individual.33 Social support can be influenced by the degree to which an individual is socially integrated into the social network, the actual received support, and the perception of an individual about the availability of the support.34 Nonetheless, our findings support the importance of maintaining good social support for frontline healthcare professionals during the pandemic. Future research is warranted to explore the strategies to maintain social support during the pandemic and potential factors that protect health workers from adverse mental health outcomes.

The study has several limitations. The sample size is small. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling; most were young adults, single, living with family, and working in public hospitals. The sample may not be representative of the occupational therapists in Hong Kong, and hence the findings may not be generalised to all occupational therapists in Hong Kong. The cross-sectional design enables analysis of results in one timepoint only. With the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, results might differ if the same survey was conducted at another timepoint. Therefore, a longitudinal study is warranted to examine the long-term impact of the pandemic on healthcare workers’ social support and mental health. In addition, control groups such as the general population or other healthcare workers were not included for comparison. We only examined perceived social support and sociodemographic factors and their correlations with depression. Other confounding factors (workloads and work-related stress, exposure to COVID-19 patients, fear of infection, and resilience)35 that might affect social support and mental health outcomes during the pandemic were not assessed.

Conclusion

Higher level of perceived social support is associated with lower level of depression. Social support might serve as a protective factor for depression among occupational therapists in Hong Kong during the pandemic.

Contributors

MHC designed the study, acquired and analysed the data, and drafted the manuscript. ATCL supervised the study and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (Reference: SBRE-20-301). Informed consent was obtained from each participant.

References

- Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Latest Situation of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Hong Kong. Available from: https://chp-dashboard.geodata.gov.hk/covid-19/en.html

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203976. Crossref

- Lam SC, Arora T, Grey I, et al. Perceived risk and protection from infection and depressive symptoms among healthcare workers in mainland China and Hong Kong during COVID-19. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:686. Crossref

- Muller AE, Hafstad EV, Himmels JPW, et al. The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: a rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Res 2020;293:113441. Crossref

- Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2020;88:901-7. Crossref

- Zhu Z, Xu S, Wang H, et al. COVID-19 in Wuhan: sociodemographic characteristics and hospital support measures associated with the immediate psychological impact on healthcare workers. EClinicalMedicine 2020;24:100443. Crossref

- Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res 2020;288:112936. Crossref

- Usta YY. Importance of social support in cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012;13:3569-72. Crossref

- Soman S, Bhat SM, Latha KS, Praharaj SK. Gender differences in perceived social support and stressful life events in depressed patients. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2016;26:22-9.

- Alsubaie M, Stain HJ, Webster LAD, Wadman R. The role of sources of social support on depression and quality of life for university students. Int J Adolesc Youth 2019;24:1-13. Crossref

- Qi M, Zhou SJ, Guo ZC, et al. The effect of social support on mental health in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Adolesc Health 2020;67:514-8. Crossref

- Naushad VA, Bierens JJ, Nishan KP, et al. A systematic review of the impact of disaster on the mental health of medical responders. Prehosp Disaster Med 2019;34:632-43. Crossref

- World Health Organization. Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) [updated 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default- source/coronaviruse/who- china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf

- Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2020;323:2133-4. Crossref

- Department of Health, The Government of Hong Kong SAR. 2017 Health Manpower Survey: Summary of the Characteristics of Occupational Therapists Enumerated. Available from: https://www. dh.gov.hk/english/statistics/statistics_hms/sumot17.html

- Chou KL. Assessing Chinese adolescents’ social support: the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Pers Individ Dif 2000;28:299-307. Crossref

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Per Assess 1988;52:30-41. Crossref

- Yu X, Tam WW, Wong PT, Lam TH, Stewart SM. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for measuring depressive symptoms among the general population in Hong Kong. Compr Psychiatry 2012;53:95-102. Crossref

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self- report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA 1999;282:1737-44. Crossref

- Lau JT, Yang X, Tsui HY, Pang E, Wing YK. Positive mental health- related impacts of the SARS epidemic on the general public in Hong Kong and their associations with other negative impacts. J Infect 2006;53:114-24. Crossref

- Gijzen M, Shields-Zeeman L, Kleinjan M, et al. The bittersweet effects of COVID-19 on mental health: results of an online survey among a sample of the Dutch population five weeks after relaxation of lockdown restrictions. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:9073. Crossref

- Hossain MM, Tasnim S, Sultana A, et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: a review. F1000 Res 2020;9:636. Crossref

- Ornell F, Schuch JB, Sordi AO, Kessler FHP. “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: mental health burden and strategies. Braz J Psychiatry 2020;42:232-5. Crossref

- Talevi D, Socci V, Carai M, et al. Mental health outcomes of the CoViD-19 pandemic. Riv Psichiatr 2020;55:137-44.

- Choi EPH, Hui BPH, Wan EYF. Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:3740. Crossref

- Ko CH, Yen CF, Yen JY, Yang MJ. Psychosocial impact among the public of the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic in Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006;60:397-403. Crossref

- Grey I, Arora T, Thomas J, Saneh A, Tohme P, Abi-Habib R. The role of perceived social support on depression and sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res 2020;293:113452. Crossref

- Kandeğer A, Aydın M, Altınbaş K, et al. Evaluation of the relationship between perceived social support, coping strategies, anxiety, and depression symptoms among hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Int J Psychiatry Med 2021;56:240-54. Crossref

- Ni MY, Yang L, Leung CMC, et al. Mental health, risk factors, and social media use during the COVID-19 epidemic and cordon sanitaire among the community and health professionals in Wuhan, China: cross-sectional survey. JMIR Ment Health 2020;7:e19009. Crossref

- Cai H, Tu B, Ma J, Chen L, Fu L, Jiang Y, Zhuang Q. Psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in Hunan between January and March 2020 during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei, China. Med Sci Monit 2020;26:e924171. Crossref

- Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, Li S, Yang N. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med Sci Monit 2020;26:e923549. Crossref

- Dambi JM, Corten L, Chiwaridzo M, Jack H, Mlambo T, Jelsma J. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of the cross- cultural translations and adaptations of the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (MSPSS). Health Qual Life Outcomes 2018;16:80. Crossref

- Cornman JC, Lynch SM, Goldman N, Weinstein M, Lin HS. Stability and change in the perceived social support of older Taiwanese adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2004;59:S350-7. Crossref

- De Kock JH, Latham HA, Leslie SJ, et al. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health 2021;21:104. Crossref