East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2024;34:91-102 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2426

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Abstract

Background: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often coexists with substance use disorders (SUDs). This study aimed to determine factors associated with ADHD symptoms among adults with SUDs in Malaysia.

Methods: Patients aged ≥18 years with a ≥1-year history of substance use who were admitted to any of the three drug rehabilitation centres in urban Malaysia for >1 month were invited to participate. Participants were interviewed using the Malay version of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test to assess substance use and the Malay version of the Adult ADHD Self-Reporting Scale to assess ADHD symptoms.

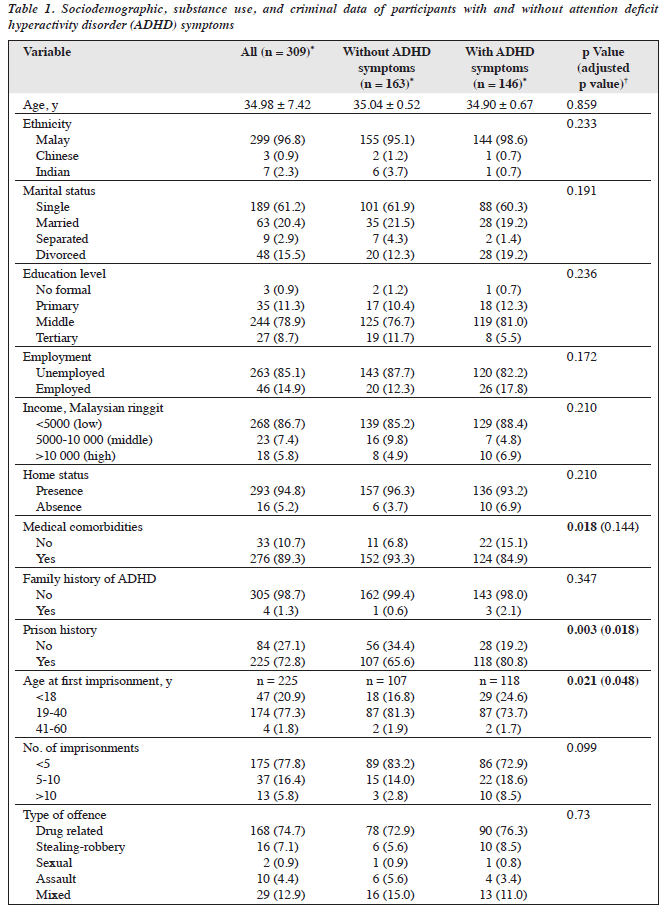

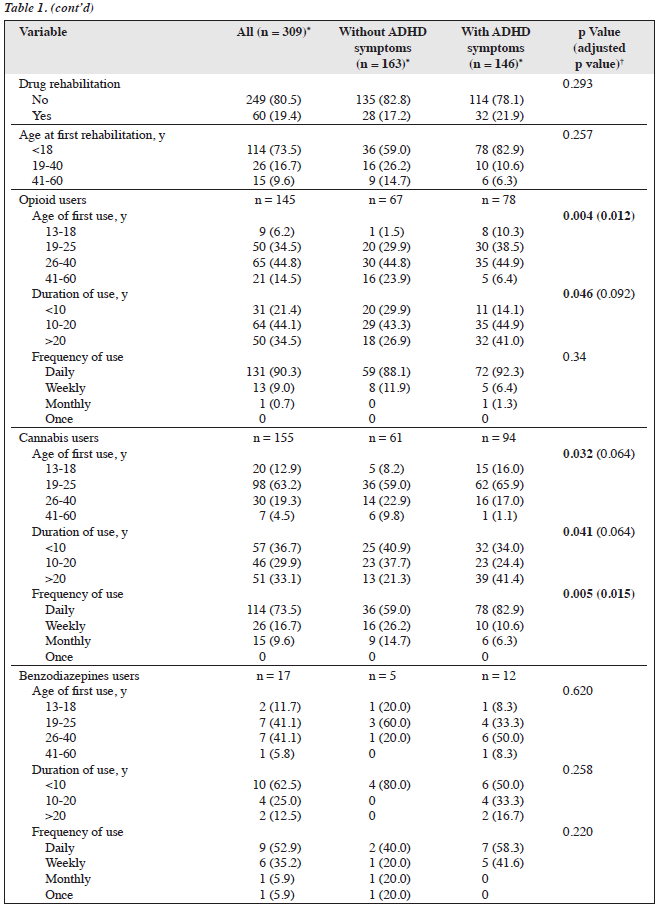

Results: The prevalence of adult ADHD symptoms among participants with SUDs was 47.2%. Compared with participants without ADHD, a lower proportion of participants with ADHD had medical comorbidities (84.9% vs 93.3%, p = 0.018), whereas a higher proportion of participants with ADHD symptoms had a history of imprisonment (80.8% vs 65.6%, adjusted p = 0.018) and first imprisonment before the age of 18 years (24.6% vs 16.8%, adjusted p = 0.048).

Conclusion: A high proportion of adults undergoing rehabilitation for SUDs have ADHD symptoms. Screening and interventions for ADHD should be integrated into SUD rehabilitation programmes.

Muhammad Rafi Md Yusop, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Selangor, Malaysia

Salina Mohamed, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, UniversitiTeknologi MARA, Selangor,Malaysia

Nor Hidayah Jaris, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Selangor,Malaysia

Aziz Jamal, Health Administration Program, Faculty of Business and Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Selangor, Malaysia

Address for correspondence: Dr Salina Mohamed, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh Campus, Selangor Branch, Selangor, Malaysia. Email: salina075@uitm.edu.my

Submitted: 14 May 2024; Accepted: 13 August 2024

In a meta-analysis in 2021, the worldwide prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) worldwide was estimated to be 2.58% in adults with a childhood onset and 6.76% in symptomatic adults (regardless of onset age).1 In Hong Kong in 2017, the estimated prevalence of ADHD among adults with psychiatric disorders was 13% to 19.3%; it was higher in men than in women (24.7% vs 17.1%).2 Adult ADHD is associated with substance and alcohol use disorders, a forensic record, and severe functional impairment.2 In Malaysia in 2018, the prevalence of ADHD was 15.8% among forensic mental health inpatients.3

Adults with ADHD commonly have coexisting psychiatric disorders including mood and anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and substance use disorders (SUDs).4

Methods

Patients aged ≥18 years with a ≥1-year history of substance use who were admitted to any of the three Cure and Care Rehabilitation Centres14 in urban Malaysia for >1 month between March 2023 and August 2023 were invited to participate. Patients were excluded if they could not read or write Malay or English, were in acute intoxication or withdrawal, or had psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, or anxiety disorder.

Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire to collect demographic data and substance use history. Participants were interviewed using the Malay version of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test to assess substance use and the Malay version of the Adult ADHD Self-Reporting Scale (ASRS) to assess ADHD symptoms. The ASRS comprises 18 questions in two parts: inattention and hyperactivity. Each question is measured on a five-point Likert scale from ‘never’ to ‘always’. Six of the questions are most predictive of symptoms consistent with ADHD and are used for screening. Participants were considered to have symptoms highly consistent with ADHD when ≥4 of the six questions were responded above ‘sometimes’ or ‘often’. Among 676 inmates, the Malay version of the ASRS has good internal consistency for the inattention subscale (Cronbach α = 0.876) and the hyperactivity subscale (Cronbach α = 0.863) subscales, as well as overall (Cronbach α = 0.925).15

The required sample size was calculated using the OpenEpi sample size calculator (www.openepi.com). Based on a 51% prevalence of ADHD among adult patients with substance use in a rehabilitation centre in a previous study,16 a sample size of 169 was needed, with a 5% precision rate and a 95% confidence interval. With an attrition rate of 20%, additional 33 participants were required and the minimum sample size was 202. A systematic sampling method was used.

Data were analysed using Stata version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States). Participants with and without ADHD symptoms were compared using the Pearson Chi-squared test, Fisher’s exact test, or Welch t-test, as appropriate. Effect sizes were calculated to quantify associations between variables. Our data had characteristics of outcome imbalance, resulting in quasi- and complete data separation. Therefore, analyses were carried out using penalised maximum likelihood estimation based on the Firth correction. The Firth logistic regression provides unbiased estimates of logistic regression, especially when dealing with rare events, quasi- and complete separation, and outcome imbalance.17-21 Univariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine associations between sociodemographic variables and substance use patterns. Multinomial logistic regression was performed to assess the effects of sociodemographic variables on the type of criminal offences committed by the participants. Ordered logistic regression was used to examine the effects of sociodemographic variables on the age of first substance use. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant; significant p values were then adjusted using the Holm-Bonferroni sequential correction method22 to adjust for the family-wise error rate and reduce the probability of type I errors.

Results

In total, 320 patients with SUDs aged 18 to 65 years were recruited. Of these, 11 were excluded owing to incomplete questionnaire responses. Of the 309 participants included, 146 (47.2%) had ADHD symptoms and 163 (52.8%) did not (Table 1). Participants with and without ADHD symptoms were comparable in terms of age, ethnicity, marital status, education level, employment status, income, home status, and family history of ADHD. However, a lower proportion of participants with ADHD had medical comorbidities (84.9% vs 93.3%, p = 0.018, Table 1), whereas a higher proportion of participants with ADHD symptoms had a history of imprisonment (80.8% vs 65.6%, adjusted p = 0.018) and first imprisonment before the age of 18 years (24.6% vs 16.8%, adjusted p = 0.048) [Table 1]. However, the two groups were comparable in terms of number of imprisonments and types of offence, as well as having undergone drug rehabilitation and age at first drug rehabilitation.

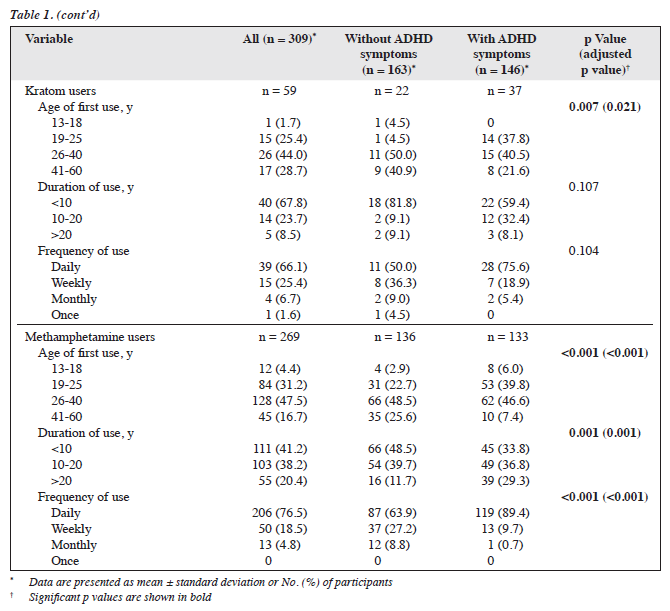

Among 145 opioid users, a high proportion of those with ADHD symptoms had first drug use between ages 13 and 18 years (10.3% vs 1.5%, adjusted p = 0.012) and duration of use of >20 years (41.0% vs 26.9%, p = 0.046) [Table 1]. Among 155 cannabis users, a higher proportion of those with ADHD symptoms had first drug use between ages 13 and 18 years (16.0% vs 8.2%, p = 0.032), duration of use of >20 years (41.4% vs 21.3%, p = 0.041), and daily frequency of use (82.9% vs 59.0%, adjusted p = 0.015). Among 17 benzodiazepine users and 59 kratom users, those with and without ADHD symptoms were comparable (except that a higher proportion of kratom users with ADHD symptoms had first drug use between ages 19 and 25 years (37.8% vs 4.5%, adjusted p = 0.021). Among 269 methamphetamine users, a high proportion of those with ADHD symptoms had first drug use between ages 13 and 18 years (6.0% vs 2.9%, adjusted p < 0.001), duration of use of >20 years (29.3% vs 11.7%, adjusted p = 0.001), and daily frequency of use (89.4% vs 63.9%, adjusted p < 0.001).

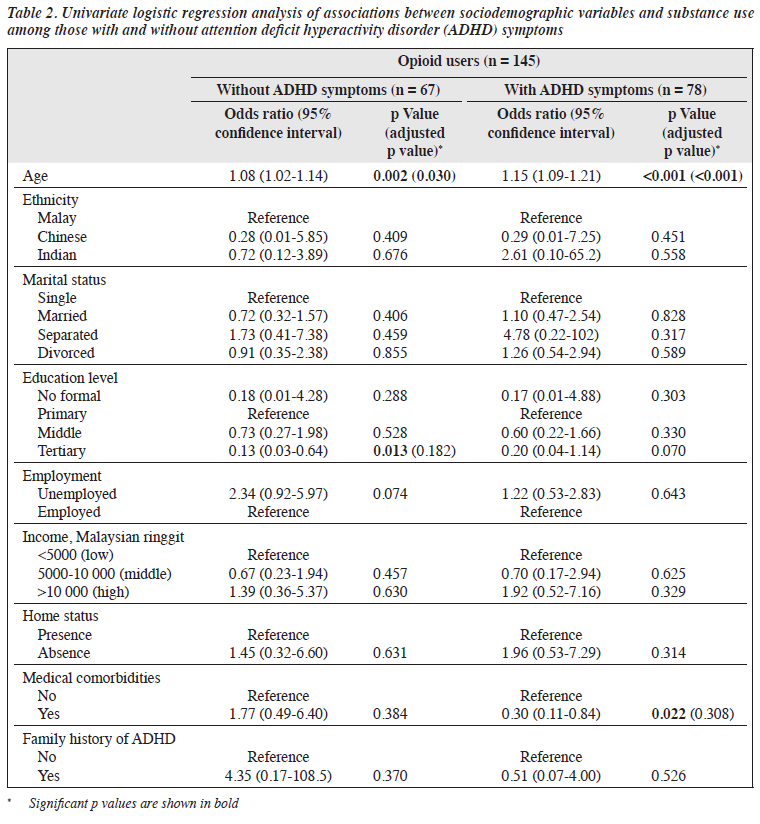

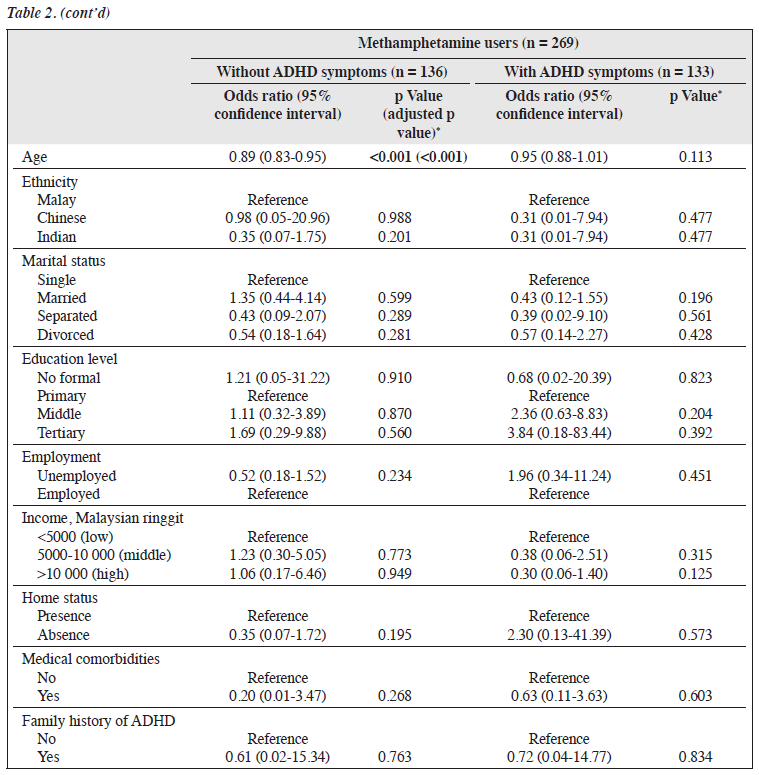

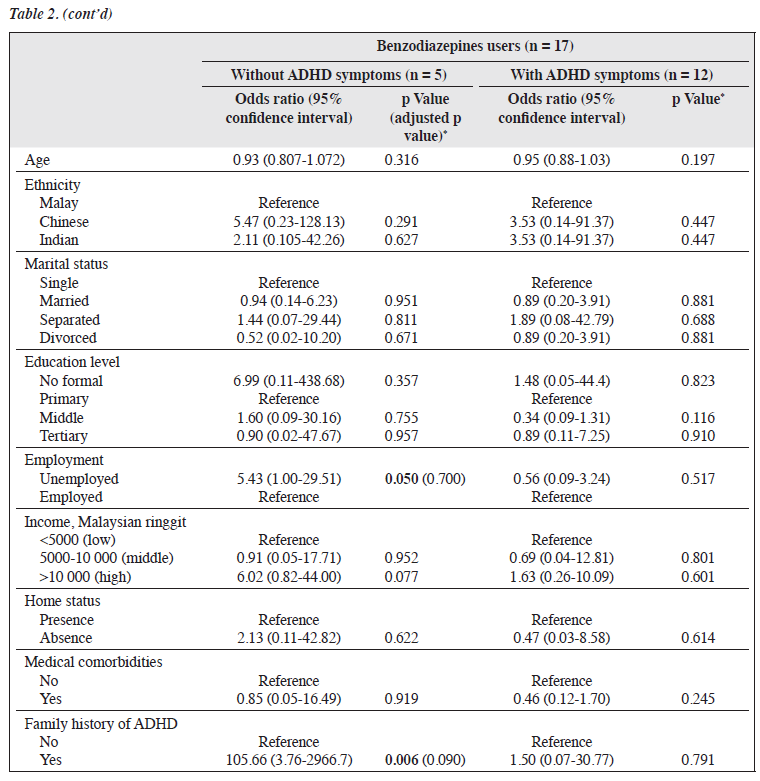

In the univariate logistic regression analysis, among 145 opioid users, age was associated with opioid use both in those with (odds ratio [OR] = 1.15, adjusted p < 0.001) and without (OR = 1.08, adjusted p = 0.030) ADHD symptoms (Table 2). A 1-year increase in age was associated with an increase of 0.14 and 0.08 log odds of opioid use among those with and without ADHD symptoms, respectively. Among 67 opioid users without ADHD symptoms, those with tertiary education were less likely to use opioids, compared with those with only primary education (OR = 0.13, p = 0.013). Among 78 opioid users with ADHD symptoms, those with medical comorbidities were less likely to use opioids, compared with those without medical comorbidities (OR = 0.30, p = 0.022). Among five benzodiazepine users without ADHD symptoms, those unemployed (OR = 5.43, p = 0.050) and those with a family history of ADHD (OR = 105.66, p = 0.006) were more likely to use benzodiazepine. Among 136 methamphetamine users without ADHD symptoms,

Table 1. Sociodemographic, substance use, and criminal data of participants with and without attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms age was inversely associated with methamphetamine use (OR = 0.89, adjusted p < 0.001). A 1-year increase in age was associated with a decrease of 0.12 log odds of methamphetamine use.

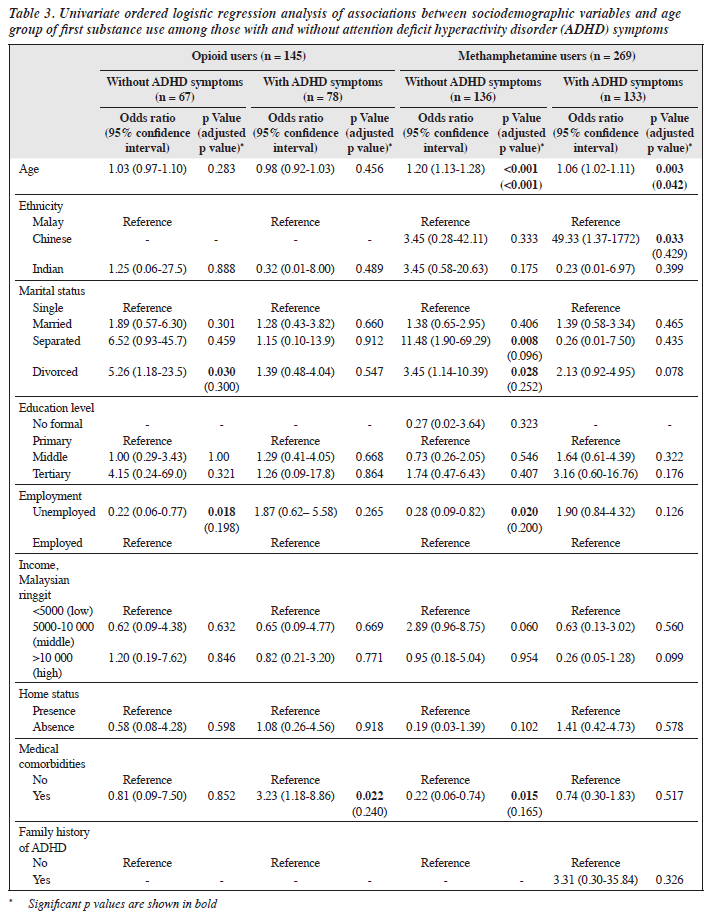

In the univariate ordered logistic regression analysis, among 67 opioid users without ADHD symptoms, being divorced was associated with a higher age group of first opioid use (OR = 5.26, p = 0.030), whereas being unemployed was associated with a lower age group of first opioid use (OR = 0.22, p = 0.018). Among 78 opioid users with ADHD symptoms, having medical comorbidities was associated with a higher age group of first opioid use (OR = 3.23, p = 0.022). Among 269 methamphetamine users, older age was associated with a higher age group of first methamphetamine use both in those with (OR = 1.06, adjusted p = 0.042) and without (OR = 1.20, adjusted p < 0.001) ADHD symptoms. Among 136 methamphetamine users without ADHD symptoms, being separated (OR = 11.48, p = 0.008) or divorced (OR = 3.45, p = 0.028) were associated with a higher age group of first methamphetamine use, whereas being unemployed (OR = 0.28, p = 0.020) and having medical comorbidities (OR = 0.22, p = 0.015) were associated with a lower age group of first methamphetamine use. Among 133 methamphetamine users with ADHD symptoms, being Chinese was associated with a higher age group of first methamphetamine use, compared with being Malay (OR = 49.33, p = 0.033).

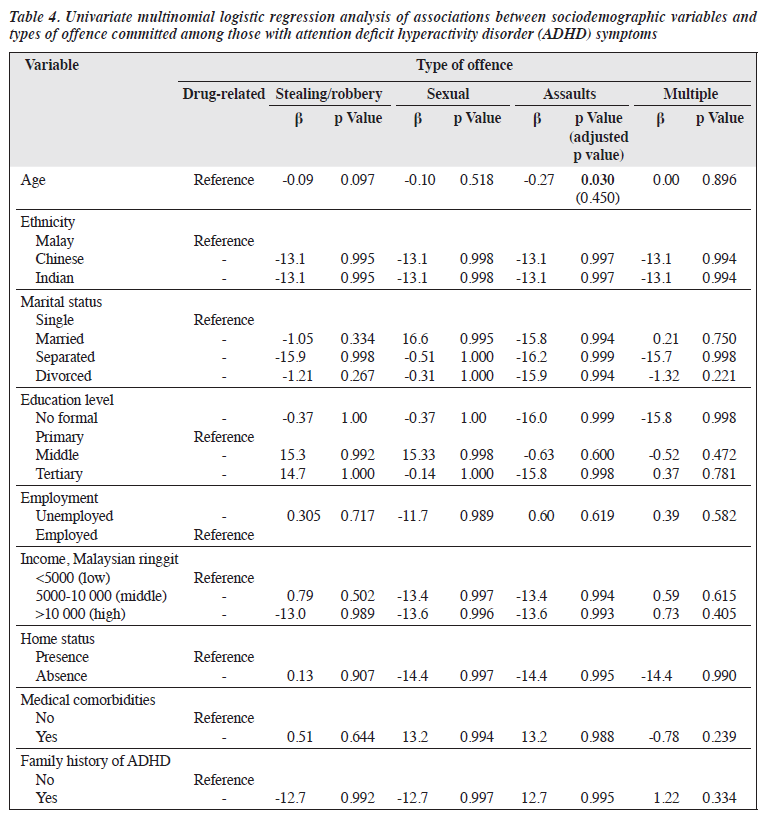

In the multinomial logistic regression analysis, among 146 participants with ADHD symptoms, a higher age was associated with lower odds of committing assaults, compared with drug-related offences (β = -0.27, p = 0.030, Table 4). A 1-year increase in age was associated with a decrease of 0.27 log odds of committing assaults.

Discussion

Among 309 participants with SUDs in Malaysia, 47.2% had ADHD symptoms, consistent with a previous study.7 The presence of ADHD symptoms among those with SUDs may be associated with sociodemographic variables and diagnostic criteria.7 However, our participants with and without ADHD symptoms did not differ significantly in terms of sociodemographic variables, consistent with a previous study.23 However, another study found that ADHD symptoms were associated with age and socioeconomic status among Japanese workers.24 These differences may be attributed to sample heterogeneity and the intricate nature of ADHD in adulthood, which is influenced by diverse environmental and genetic factors.24

The association between ADHD and cannabis use may be attributed to the effect of cannabis on the hippocampus, cerebellum, frontal cortex, and postcentral gyrus, all of which are implicated in ADHD.25,26 Cannabis use can further exacerbate ADHD-related dopamine deficits by reducing striatal dopamine synthesis, potentially compounding the existing neurotransmitter imbalance.26 Pharmacological interactions between methylphenidate and mu opioid receptors may be a pathway for preventing stimulant abuse.27 Furthermore, the sedative and mood- stabilising effects of opioids through mu receptor activation might alleviate ADHD symptoms such as anxiety and depression.28 This mechanism aligns with observations that individuals with chronic non-cancer pain who switch from stimulants to opioids for ADHD symptom management. This suggests a potential association between opioid use and ADHD symptomatology.29

ADHD is associated with impulsivity and sensation- seeking tendencies, which could increase the likelihood of early cannabis use in adolescence as a form of self- medication to alleviate symptoms such as hyperactivity or inattention.30 The effects of methamphetamine can vary between individuals with and without ADHD. Individuals with ADHD who use methamphetamine may experience improvements in cognitive function, sustained attention, and arousal, all of which are beneficial for ADHD symptoms.31 However, individuals without ADHD who use methamphetamine may experience enhanced mood, increased blood pressure, behavioural disinhibition, and euphoria, all of which can lead to addiction.32

Individuals with adult ADHD are at a higher risk of criminal issues including increased rates of imprisonment history and drug-related offences.33 Those with ADHD are more likely to have first imprisonment before the age of 18 years but have fewer number of imprisonments in their lives.33 The effect of ADHD on criminal outcomes is disproportionate, particularly among individuals with SUDs.33 Adolescents and adults with ADHD are associated with a two- to three-fold increase in the risk of arrests, convictions, and incarcerations.33 A significant percentage of imprisoned adults with ADHD have a lifetime history of antisocial personality disorder; this emphasises the complex interplay between ADHD and criminal issues.34

The results of our study underscore the necessity for integrated approaches in clinical practice and policy development to address both ADHD symptoms and SUDs. The complex interplay between these conditions requires comprehensive and coordinated treatment strategies. Management should involve multifaceted approaches that include pharmacological treatments for ADHD, evidence-based psychotherapies, and targeted interventions for SUDs. By managing ADHD symptoms and SUDs concurrently, treatment outcomes can be optimised, and rates of recidivism can be significantly reduced.

People attending substance use rehabilitation programmes should be screened for ADHD symptoms to facilitate early diagnosis and interventions. Simultaneous management of ADHD symptoms and SUDs can reduce relapse risks and enhance overall rehabilitation success. In terms of policy development, there is a pressing need to prioritise the access to comprehensive care and support services. Improved coordination between mental health and SUD treatment can facilitate care delivery.

The present study has several limitations. The cross- sectional design restricts the ability to infer causality; longitudinal studies to follow up ADHD symptoms and SUD outcomes over time are warranted. The small sample size and involvement of only three rehabilitation centres may have limited the statistical power and generalisability of the findings. The self-report measures for substance use history before rehabilitation may have introduced response bias and recall bias. Objective clinical assessments should have been used to enhance validity. Our results should be interpreted cautiously. To reduce type I error, the p values were adjusted using the Holm-Bonferroni correction method. However, this method may affect the statistical power, causing type II error and publication bias. Therefore, it is recommended to focus on the effect size and confidence intervals rather than just p values. There may have been selection bias because only inpatients who were admitted to the rehabilitation centres for ≥1 month were included. The sample may not be representative of all patients with SUDs, because only those admitted voluntarily were included, who differ from those admitted through legal or correctional channels. Future studies should include patients in more comprehensive settings and motivations for treatment.

Conclusion

A high proportion of adults undergoing rehabilitation for SUDs have ADHD symptoms. Screening and interventions for ADHD should be integrated into SUD rehabilitation programmes.

Contributors

All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding / support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia (reference: 100 - FPR (PT.9/19) (FERC-02-23-03)_2.0)). The participants provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures and for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Director General of Malaysia National Anti-Drug Agency (NADA) for the permission to conduct the study. Special thanks to Ahmad Akmal bin Ahmad Zailan, Nikmat Mohamad Bin Md Yusop, and NADA Officers for their contribution in data collection.

References

- Song P, Zha M, Yang Q, Zhang Y, Li X, Rudan I. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Global Health 2021;11:04009.

- Leung VM, Chan LF. A cross-sectional cohort study of prevalence, co- morbidities, and correlates of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder among adult patients admitted to the Li Ka Shing Psychiatric Outpatient Clinic, Hong Kong. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2017;27:63-70.

- Woon LSC, Zakaria H. Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a Malaysian forensic mental hospital: a cross-sectional study. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2019;29:118-23.

- Mirza H, Al-Huseini S, Al-Jamoodi S, et al. Socio-demographic and clinical profiles of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder patients in a university hospital in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2022;22:206-11.

- Badrfam R, Zandifar A, Barkhori Mehni M, Farid M, Rahiminejad F. Comorbidity of adult ADHD and substance use disorder in a sample of inpatients bipolar disorder in Iran. BMC Psychiatry 2022;22:480.

- Manni C, Cipollone G, Pallucchini A, Maremmani AGI, Perugi G, Maremmani I. Remarkable reduction of cocaine use in dual disorder (adult attention deficit hyperactive disorder/cocaine use disorder) patients treated with medications for ADHD. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:3911.

- Rohner H, Gaspar N, Philipsen A, Schulze M. Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among substance use disorder (SUD) populations: meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023;20:1275.

- Coetzee C, Truter I, Meyer A. Differences in alcohol and cannabis use amongst substance use disorder patients with and without comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. S Afr J Psychiatr 2022;28:1786.

- Assayag N, Berger I, Parush S, Mell H, Bar-Shalita T. Attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms, sensation-seeking, and sensory modulation dysfunction in substance use disorder: a cross sectional two-group comparative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:2541.

- Shoham R, Sonuga-Barke E, Yaniv I, Pollak Y. ADHD is associated with a widespread pattern of risky behavior across activity domains. J Atten Disord 2021;25:989-1000.

- Vilar-Ribó L, Sánchez-Mora C, Rovira P, et al. Genetic overlap and causality between substance use disorder and attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2021;186:140-50.

- Vélez-Pastrana MC, González RA, Ramos-Fernández A, Ramírez Padilla RR, Levin FR, Albizu García C. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in prisoners: increased substance use disorder severity and psychiatric comorbidity. Eur Addict Res 2020;26:179-90.

- Libutzki B, Ludwig S, May M, Jacobsen RH, Reif A, Hartman CA. Direct medical costs of ADHD and its comorbid conditions on basis of a claims data analysis. Eur Psychiatry 2019;58:38-44.

- Cure and Care Rehabilitation Centre. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Accessed 1 December 2022. Available from: https://www.adk.gov.my/ en/faq-pusat-pemulihan-penagihan-narkotik.

- Syahril MY, Hazli Z, Fairuz NAR. The psychometric properties of Malay language Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Self-Report Scale (ASRS) and the prevalence of adult ADHD and its associated factors among inmates at Seremban Prison. The 22nd Malaysian Conference on Psychological Medicine (MCPM) Theme: The Biopsychosocial and Collaborative Models in Psychiatry: Walking the Talk; 2018.

- Miovský M, Lukavská K, Rubášová E, Šťastná L, Šefránek M, Gabrhelík R. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among clients diagnosed with a substance use disorder in the therapeutic communities: prevalence and psychiatric comorbidity. Eur Addict Res 2021;27:87-96.

- Heinze G, Schemper M. A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Stat Med 2002;21:2409-19.

- Doerken S, Avalos M, Lagarde E, Schumacher M. Penalized logistic regression with low prevalence exposures beyond high dimensional settings. PLoS One 2019;14:e0217057.

- Šinkovec H, Geroldinger A, Heinze G. Bring more data! A Good Advice? Removing separation in logistic regression by increasing sample size. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:4658.

- Puhr R, Heinze G, Nold M, Lusa L, Geroldinger A. Firth’s logistic regression with rare events: accurate effect estimates and predictions? Stat Med 2017;36:2302-17.

- Gim TH, Ko J. Maximum likelihood and Firth logistic regression of the pedestrian route choice. Int Reg Sci Rev 2016;40:616-37.

- Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat 1979;6:65-70.

- Katzman MA, Bilkey TS, Chokka PR, Fallu A, Klassen LJ. Adult ADHD and comorbid disorders: clinical implications of a dimensional approach. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:302.

- Suzuki T, Wada K, Nakazato M, Ohtani T, Yamazaki M, Ikeda S. Associations between adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) traits and sociodemographic characteristics in Japanese workers. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2023;19:759-73.

- Mitchell JT, Sweitzer MM, Tunno AM, Kollins SH, McClernon FJ. “I use weed for my ADHD”: a qualitative analysis of online forum discussions on cannabis use and ADHD. PLoS One 2016;11:e0156614.

- Rasmussen J, Casey BJ, van Erp TG, et al. ADHD and cannabis use in young adults examined using fMRI of a Go/NoGo task. Brain Imaging Behav 2015;10:761-71.

- Zhu J, Spencer TJ, Liu-Chen LY, Biederman J, Bhide PG. Methylphenidate and μ opioid receptor interactions: a pharmacological target for prevention of stimulant abuse. Neuropharmacology 2011;61:283-92.

- Al Rashid S. The role of probiotics in various diseases. Int J Hum Health Sci 2024;5:375-6.

- Beliveau CM, McMahan VM, Arenander J, et al. Stimulant use for self-management of pain among safety-net patients with chronic non- cancer pain. Subst Abus 2022;43:179-86.

- Cawkwell PB, Hong DS, Leikauf JE. Neurodevelopmental effects of cannabis use in adolescents and emerging adults with ADHD: a systematic review. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2021;29:251-61.

- Lopera SD, O’Kane VM, Goldhirsh JL, Piper BJ. Regional disparities in prescription methamphetamine and amphetamine distribution across the United States. J Atten Disord 2023;27:1322-331.

- Ares-Santos S, Granado N, Moratalla R. The role of dopamine receptors in the neurotoxicity of methamphetamine. J Intern Med 2013;273:437-53.

- Anns F, D’Souza S, MacCormick C, et al. Risk of criminal justice system interactions in young adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: findings from a national birth cohort. J Atten Disord 2023;27:1332-42.

- Etterlid-Hägg V, Pauli M, Howner K. A comparative study of prison inmates with and without ADHD: which neuropsychological and self-report measures are most effective in detecting ADHD within correctional services? J Atten Disord 2023;27:721-30.