East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2010;20:7-13

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Prof Ram Kumar Solanki, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Sawai Man Singh Medical College, Jaipur, India.

Dr Paramjeet Singh, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Sawai Man Singh Medical College, Jaipur, India.

Dr Aarti Midha, MD, SDM Hospital, Jaipur, India.

Dr Karan Chugh, MBBS, Rajindera Hospital, Government Medical College, Patiala, India.

Dr Mukesh Kumar Swami, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, Sawai Man Singh Medical College, Jaipur, India.

Address for correspondence: Prof RK Solanki, D-840, Malviya Nagar, Jaipur, India.

Tel: 0141-2724345; Email: solanki_ramk@yahoo.co.in

Submitted: 4 May 2009; Accepted: 22 July 2009

Abstract

Objective: To assess and compare the quality of life and disability in patients with schizophrenia and obsessive compulsive disorder.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was carried out in the outpatient psychiatry clinics at Jaipur of India. Fifty patients with obsessive compulsive disorder and 47 with schizophrenia (diagnosed as per criteria of the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases), and with a minimum duration of 2 years on maintenance treatments, were evaluated. Evaluation was based on the World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument, the Global Assessment of Functioning scale, and the Indian Disability Evaluation Assessment Scale. The collected data were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics.

Results: Regarding quality of life domains, there was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. Obsessive compulsive disorder patients had lower scores on all domains of disability, all such differences being statistically significant.

Conclusions: The deleterious effect of illness on quality of life and functioning occur not only in schizophrenic but also in obsessive compulsive disorder patients. Thus management should be planned with this consideration to yield better outcomes in both conditions.

Key words: Disability evaluation; Obsessive-compulsive disorder; Quality of life; Schizophrenia

摘要

目的:评估和比较精神分裂症和强迫症患者的生活质素和残障程度。

方法:这项在印度Jaipur医院精神科进行的横断面研究以门诊病人为对象,并根据世界卫生组织生活质素测定量表简化版、整体功能评估量表,以及印度残障评估与评鑑量表,对接受至少2年

康复治疗的50名强迫症和47名精神分裂症患者(以国际疾病分类第十版作为诊断标準)作出评估;有关数据以敍述和推理统计学进行分析。

结果:在生活质素方面,强迫症和精神分裂症患者并没有明显分别。不过,强迫症患者在各种评估障碍範畴的得分却较低,分别也较显著。

结论:病症对生活质素和功能状态的不良影响并不局限於精神分裂症患者,强迫症患者也不容忽视。因此,医护人员应在治疗方案上多加谨慎,使这两类患者能达至更佳治疗效果。

关键词:障碍评估、强迫症、生活质素、精神分裂症。

Introduction

Mental, behavioural, and social health problems are increasingly problematic all over the world. Yet they have received scant attention other than in wealthier, industrialised nations.1 Although the burden of illness resulting from psychiatric and behavioural disorders is enormous, it is grossly under-represented in conventional public health statistics, which tend to focus on mortality rather than morbidity or dysfunction.1

In 1990, the worldwide global burden of disease for neuropsychiatric disorders, as measured by disability- adjusted life years (DALYs), was estimated to be 6.8%.2 Psychiatric disorders account for 5 of the 10 leading causes of disability as measured by years lived with a disability.2 The overall DALYs burden for neuropsychiatric disorders is projected to increase to 15% by the year 2020, which is proportionately larger than that for the increase in cardiovascular disease.3

The World Health Organization (WHO)’s definition of health4 emphasised the importance of well-being besides absence of disease as an essential component of health, to which not much attention has been paid for a considerable period of time. The focus has gradually shifted towards understanding the consequences of health conditions in terms of disabilities that are experienced at the level of the body, person, and society. In addition, the subjective components of health experience (‘quality of life’ [QOL], ‘subjective well-being’) have also acquired a definite place in the understanding of health and its consequences.5

There has been little examination of the extent to which presence of persistent obsessions and compulsions impacts on the QOL and disability of persons with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). A review of the impact of anxiety disorders on QOL enumerated the profound personal, social, and financial costs, though there was a striking dearth of studies on patients with OCD.6

Schizophrenia is a severe and debilitating disorder, which affects general health, functioning, autonomy, subjective well-being, and life satisfaction of those who suffer from it. Despite 50 years of pharmacological and psychosocial interventions, schizophrenia remains one of the top causes of disability in the world.7

We undertook this study to assess, quantify, and compare the disability and QOL in patients suffering from schizophrenia and OCD attending our psychiatric centre in Jaipur. This study has been carried out to assess the impact of mental illnesses on different domains of patient’s life. This might help us to understand, plan, and anticipate appropriately with respect to management and rehabilitation. Schizophrenia being a psychotic disorder, and OCD being a neurotic disorder, were chosen to compare their disabling potential and QOL.

Methods

Study Design

In this study, 50 consecutive demographically comparable patients with OCD and 50 with schizophrenia diagnosed as per the criteria of the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) were reviewed. All of them had a minimum duration of illness (DOI) of 2 years. Moreover, they had all attended the outpatient department (OPD) at the psychiatric centre or psychiatric clinic at Sawai Man Singh (SMS) Medical College, Jaipur, India for maintenance treatment, and fulfilled the criteria detailed below.

The OCD patients fulfilling the respective diagnostic criteria as per ICD-10 were between 18 and 60 years of either gender, and in receipt of maintenance treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. The schizophrenia group of patients fulfilled analogous diagnostic and entry criteria, and were in receipt of maintenance treatment with an atypical antipsychotic, usually risperidone (to maintain homogeneity of the sample). Patients who were illiterate, or had a primary diagnosis of depression or any other co- morbid psychiatric disorder, or any chronic physical illness, organic brain disorder or history of substance dependence were excluded from the study. To be eligible as a caregiver for each patient, he / she must have had at least reasonable contact with the patient (at least every 2 weeks) and over 16 years old.8 Three patients dropped out of schizophrenia group because they felt exhausted being interviewed and did not feel able to complete the pro forma.

Study Instruments

The following instruments were used in this study:

- A specially designed pro forma was used for thorough evaluation of the patients. It included the socio-demographic data sheet and clinical profile sheet.

- Developed by Goodman et al,9 the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS) consists of a 10-item clinician-rated scale for assessing the severity of obsessive compulsive symptoms in patients with OCD. It was designed for use as a semi-structured interview, using the questions provided in the listed order. Items are rated on a 0 to 4 scale (0 = none, 4 = extreme) and based upon information obtained as reported and observed during interview.

- Positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS): this 30-item, 7-point rating instrument is conceived as a carefully defined and operationalised method that evaluates positive, negative or other symptom dimensions on the basis of a formal semi-structured clinical interview and other informational sources. In these 30 items, 7 are grouped to form a positive scale measuring symptoms that are superadded to a normal mental status; the other 7 items constitute negative scale assessing features absent from a normal mental status. The remaining 16 items constitute a general psychopathology scale that gauges the overall severity of schizophrenic disorder by summation of each of the item scores.10

- The WHOQOL-BREF instrument is a structured self- reported interview developed by the WHO division of mental health. It consists of 26 items designed to assess a person’s QOL. It assesses patients under 4 domains: physical, psychological, social, and environmental. Its psychometric properties have been found to be comparable to that of the full version of the WHOQOL-100 tool.11

- The Indian Disability Evaluation Assessment Scale (IDEAS) was developed by the rehabilitation committee of Indian Psychiatric society. It has 4 items: self-care; interpersonal activities (social relationship); communication and understanding; and work. Each item is scored between 0 and 4. The global disability score is calculated by adding the total disability score (ie total score of the above 4 items) and the DOI score (1 means a duration of illness < 2 years, 2 for 2-5 years, 3 for 6-10 years, and 4 for > 10 years). It has been tested in various centres. The alpha value of 0.87 indicates good internal consistency for its items.12

- The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale measures the level of functioning of patients; it was developed in early 1990 to rate Axis V of the 4th edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. It is a clinician-rated 100-point scale based on all available information with a clear description of 10-point intervals.13

Operational Procedures

Subjects in both groups who met the criteria laid down for the purpose of this study were counselled about it, and written consent obtained from patients and accompanying primary caregivers. Most patients were interviewed immediately after their registration at the psychiatric centre OPD of SMS Medical College, Jaipur, during the period May 2005 to April 2006. For patients whose caregivers were in a hurry to return home or to office and could not stay for interview, arrangements were made to interview them at an alternative time.

The interview was semi-structured and all information was recorded in a carefully designed structured pro forma. Following this, the OCD and schizophrenic patients were administered the YBOCS and PANSS, respectively. Furthermore all the patients were subjected to detailed evaluation using WHOQOL-BREF, IDEAS, and GAF instruments.

Statistical Analysis

Mean (standard deviation [SD]) and percentages were used for descriptive purposes. Chi-square tests were applied to compare the socio-demographic and clinical variables in both groups. Student’s t test was applied for group comparisons of demographic variables, clinical characteristics, QOL, disability, and GAF.

Results

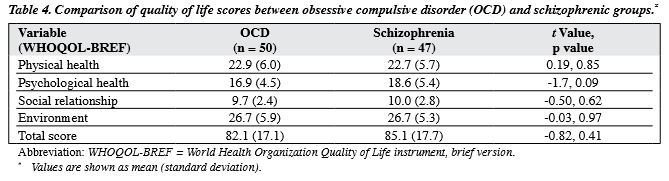

The mean (SD) age of the OCD subjects was 29 (9) years and that of the schizophrenic patients was 36 (11) years. Most respondents included in our study were married males, following the Hindu religion, living in joint families, and having an urban background. The majority of patients in both groups had attained a matriculation or higher level of education (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference between the groups with respect to socio-demographic and clinical variables (Tables 1 and 2). The OCD patients showed lower mean scores than the schizophrenic patients on all domains of disability, all differences being statistically significant. The former also had a higher mean GAF score than the schizophrenics, which was also statistically significant. Regarding QOL domains, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups (p > 0.05) [Tables 3 and 4].

Discussion

Psychological Measures

The OCD patients had moderate obsessive compulsive symptoms as reflected in the mean YBOCS score of 13.8 (SD = 8.2), with the obsession score being higher than the compulsion score. The lower score in the current study sample was possibly because all subjects in this study were receiving maintenance treatment and thus their symptoms might have been partially controlled.

The schizophrenic patients with a mean total PANSS score of 57.1 reflected low level of psychopathology. This is understandable as schizophrenics included in the study were taking maintenance treatment.

Global Assessment of Functioning and Quality of Life

Of the 47 patients with schizophrenia, 25 had moderate disability (≥ 40%) and 22 had mild disability (< 40%). Whilst a majority of OCD patients (43 of 50) had mild disability, only 7 had moderate disability. Mean GAF scores of OCD and schizophrenic patients were 66.6 and 55.0 respectively (Table 3), which means there was mild functional impairment in OCD patients and moderate functional impairment in those with schizophrenia. Mild-to- moderate functional impairment is explained by the fact that both groups were taking maintenance treatment. Steketee14 reported an average GAF score of 40 (range, 15-61) in 55 inpatients with OCD (major impairment in several areas). This contrasts with more typical GAF scores of 50 to 60 in their outpatient samples.14

Table 4 indicates the existence of impoverished QOL among OCD and schizophrenic patients. Patients with chronic illnesses suffer from more than just symptoms, as such illness affect QOL.

On QOL measures, OCD and schizophrenic patients had the lowest scores on the social relationship domain. Patients with chronic mental illness dislike the stigma of mental illness, which excludes them from social life. They are subject to many different kinds of formal and informal discriminations. In OCD patients moreover, social relationships frequently suffer due to the overriding focus on completion of rituals. This finding was also noted in earlier studies on OCD, which consistently reported more problems in social relationships in these patients.15,16

In this study, low scores on the social relationship domain of QOL in schizophrenics could be due to the negative symptoms these patients presented with; among which, asociality, avolition, and apathy are known to be prominent. This finding is supported by an earlier study by Gupta et al.17

Group Comparisons

The OCD patients were found to have lower mean scores that were statistically significant on all domains of disability, indicating that they were less disabled than the schizophrenic patients (Table 3). This finding is consistent with the study by Mohan et al,18 but contrary to that Bobes et al19 who found higher level of disability in OCD patients than schizophrenics in the area of social and occupational functioning. Another report20 revealed that OCD patients had greater disruption of their careers and relationships with family and friends.

On the GAF measure, OCD patients had significantly higher scores than the schizophrenics, indicating better ability to function. On QOL domains, evidently there were no statistically significant differences between the groups.

Lowering of expectations seems to be a mechanism preferred by the schizophrenics living in the community, in order to maintain self-esteem and subjective well-being. While subjectively assessed QOL of schizophrenic patients living in the community is mostly lower than that of healthy controls, it is surprising how many of these patients are satisfied when their QOL is assessed by quantitative scales of subjective well-being.20 Some studies even find no differences compared to the general population.21

This finding is quite similar to a comparative study by Bobes et al19 regarding OCD and schizophrenic patients on maintenance treatment, which reported similar QOL in both groups using subscales of the 36-item Short Form (SF- 36) survey like bodily pain, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health. The scores were even better in the physical health domain (physical functioning, role physical, and general health substances). The difference found in the area related to physical health was surprising to some extent. Since the role physical area of the SF-36 scale refers to role limitation due to physical problems, conceivably schizophrenic patients were less able to differentiate their role limitations as due to physical or emotional problems.

Health-related QOL was similar in OCD and schizophrenic patients as in the report by Calvocoressi et al.22 This is particularly relevant because schizophrenia has traditionally been considered the most devastating psychotic illness.

Most QOL studies have been conducted in developed countries, but very few published studies from developing countries.23 In developing countries, differences due to cultural factors influencing the prognosis of psychiatric disorders (especially in schizophrenia) have been documented by Kulhara.24 In India, most psychiatric patients live with their families in the community. There is some evidence to suggest that the perception of QOL by Indians differs from that of persons living in developed countries.17 According to Chaturvedi,25 Indians gave priority to peace of mind and spiritual satisfaction over physical and psychological functioning, while Europeans gave highest priority to physical functioning.26

Limitations

The results of the current study should be interpreted against the background of the following limitations, which might have affected our observations:

- Small sample size might have affected results, for example; difference in psychological health subscale of the WHOQOL (p = 0.09) may reached statistical significance in a larger sample.

- The current study was based on an exclusively hospital-based outpatient sample that might not be representative of patients in the community.

- The current study included patients with DOI of 2 years or more to make the sample homogenous, which limits the generalisation of results to OCD and schizophrenic patients having an acute illness.

- The WHOQOL-BREF used in the current study is a generic instrument that was not designed specifically for OCD and schizophrenic patients. Using a combination of both generic and specific instruments may be more sensitive and accurate in reflecting the clinical impact.

- As chronic stable patients were included in this study, data from patients with more severe illness were missing.

Conclusions

This study confirms disability and poor QOL in patients with OCD and schizophrenia despite significant improvements associated with pharmacological treatment. Chronic stable patients showing mild-to-moderate disability also require interventions that enhance functioning and QOL and thus decrease disabilities.

References

- Kumar N. Developments in mental health scenario: need to stop exclusion — dare to care. ICMR Bulletin 2001; Volume 31, Number 4.

- World Bank. World Development Report 1993: investing in health. New York, Oxford University Press; 1993: 213.

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD. The global burden of diseases: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Boston, Harvard School of Public Health, World Health Organization and World Bank; 1996: 325.

- World Health Organization. WHO Constitution. Geneva: WHO; 1948.

- Saxena S. Functioning, disability and quality of life assessment in mental health. In: Bhugra D, Ranjith G, Patel V, editors. Handbook of psychiatry: a South Asian perspective. New Delhi: Byword Viva Publishers; 2005.

- Mendlowicz MV, Stein MB. Quality of life in individuals with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:669-82.

- Murray CL, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1996.

- Szmukler GI, Burgess P, Herrman H, Benson A, Colusa S, Bloch S. Caring for relatives with serious mental illness: the development of the Experience of Caregiving Inventory. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1996;31:137-48.

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989;46:1006- 11.

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987;13:261-76.

- Saxena S, Chandiramani K, Bhargava R. WHOQOL-Hindi: a questionnaire for assessing quality of life in health care settings in India. World Health Organization Quality of Life. Natl Med J India 1998;11:160-5.

- Indian Psychiatric Society. IDEAS (Indian Disability Evaluation and Assessment Scale) — a scale for measuring and quantifying disability in mental disorders. Chennai, Indian Psychiatric Society; 2002.

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976;33:766-71.

- Steketee G. Disability and family burden in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Can J Psychiatry 1997;42:919-28.

- Koran LM, Thienemann ML, Davenport R. Quality of life for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:783- 8.

- Stein DJ, Roberts M, Hollander E, Rowland C, Serebro P. Quality of life and pharmaco-economic aspects of obsessive-compulsive disorder. A South African survey. S Afr Med J 1996;86(12 Suppl):S1579,1582- 5.

- Gupta S, Kulhara P, Verma SK. Quality of life in schizophrenia and dysthymia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998;97:290-6.

- Mohan I, Tandon R, Kalra H, Trivedi JK. Disability assessment in mental illnesses using Indian Disability Evaluation Assessment Scale (IDEAS). Indian J Med Res 2005;121:759-63.

- Bobes J, González MP, Bascarán MT, Arango C, Sáiz PA, Bousoño M. Quality of life and disability in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Psychiatry 2001;16:239-45.

- Lehman AF, Ward NC, Linn LS. Chronic mental patients: the quality of life issue. Am J Psychiatry 1982;139:1271-6.

- Larsen EB, Gerlach J. Subjective experience of treatment, side-effects, mental state and quality of life in chronic schizophrenic out-patients treated with depot neuroleptics. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996;93:381-8.

- Calvocoressi L, Libman D, Vegso SJ, McDougle CJ, Price LH. Global functioning of inpatients with obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, and major depression. Psychiatr Serv 1998;49:379-81.

- Solanki RK, Singh P, Midha A, Chugh K. Schizophrenia: impact on quality of life. Indian J Psychiatry 2008;50:181-6.

- Kulhara P. Outcome of schizophrenia: some transcultural observations with particular reference to developing countries. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994;244:227-35.

- Chaturvedi SK. What’s important for quality of life to Indians — in relation to cancer. Soc Sci Med 1991;33:91-4.

- van Knippenberg FC, de Haes JC. Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: psychometric properties of instruments. J Clin Epidemiol 1988;41:1043-53.