East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2024;34:128-33 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2447

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Abstract

Background: Anxiety is common among house officers. Psychological inflexibility increases the risk of anxiety. This study aimed to determine the associations between anxiety and sociodemographic factors, work-related variables, and psychological inflexibility, and to identify predictors for anxiety among house officers in a hospital in Malaysia.

Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted at Hospital Tengku Ampuan Rahimah, Klang, Selangor, Malaysia. House officers were recruited from seven departments (general surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology, paediatrics, orthopaedics, emergency, anaesthesiology, and psychiatry) between December 2023 and March 2024 using convenience sampling. Participants were asked to rate their levels of psychological flexibility (using the seven-item Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II) and anxiety (using the seven-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale [AAQ-II]), as well as their perceived factors for anxiety.

Results: In total, 43 male and 95 female participants (mean age, 27.5 years) were included in the analysis. Of the 138 participants, 75 (54.3%) were classified as having anxiety. Participants with anxiety were more likely to have a psychiatric condition (10.7% vs 1.6%, p=0.031), work more hours per week (73.95 vs 67.84, p=0.017), and have higher AAQ-II scores (31.61 vs 19.63, p<0.001). Common factors that the house officers perceived to be associated with anxiety included poor work-life balance (85.5%), hospital bureaucracy (77.5%), and performance pressure (73.9%). Predictors for anxiety were the AAQ-II score (adjusted odds ratio=1.19, p<0.001) and working hours per week (adjusted odds ratio=1.04, p=0.034).

Conclusion: Psychological inflexibility and excessive working hours are predictors for anxiety among house officers in a hospital in Malaysia.

Nur Rasyidah Binti Mohd Sabri, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh Campus, Selangor, Malaysia

Azlina Wati Binti Nikmat, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh Campus, Selangor, Malaysia

Salina Binti Mohamed, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh Campus, Selangor, Malaysia

Norni Binti Abdullah, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital Tengku Ampuan Rahimah, Klang, Selangor, Malaysia

Address for correspondence: Dr Azlina Wati Binti Nikmat, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh Campus, Selangor, Malaysia. Email: azlinawati@uitm.edu.my

Submitted: 5 September 2024; Accepted: 20 November 2024

In Malaysia, house officers are required to undergo mandatory supervised clinical training before registration as practising doctors. There are six compulsory postings, and each rotation lasts for at least 4 months. House officers often present with psychological distress (such as anxiety), which affects functioning, quality of life, commitment, and performance. The prevalence of anxiety among house officers in Malaysia has been reported as 33.7%1; factors associated with anxiety are mainly work-related stressors such as performance pressure, poor relationships with colleagues or superiors, lack of career pathway, frustration with hospital bureaucracy, poor work-life balance, and avoidance-based coping strategies.2-5

Psychological flexibility is the capacity to accept, adapt, and change in response to changing internal and external stimuli, whereas psychological inflexibility is the incapacity to do so.6-8 Psychological flexibility is a mediator in the manifestation of psychological distress such as anxiety. Thus, a high level of psychological inflexibility is associated with an increased risk of anxiety and poor overall psychological health. Psychological inflexibility can worsen stress and lead to the development of depression and anxiety.6 A population-based study in Sweden showed that psychological inflexibility was positively correlated with anxiety symptoms.9 Similarly, psychological inflexibility is a mediator of the negative impact on anxiety among senior undergraduate and graduate students of healthcare careers (medicine, nursing, and clinical psychology).10 This study aimed to determine the associations between anxiety and sociodemographic factors, work-related variables, and psychological inflexibility, and to identify predictors for anxiety among house officers in a hospital in Malaysia.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted at Hospital Tengku Ampuan Rahimah, Klang, Selangor, Malaysia, which is the second-busiest hospital for inpatient admissions and the busiest for outpatient services in Malaysia.11 House officers aged ≥18 years were recruited from seven departments (general surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology, paediatrics, orthopaedics, emergency, anaesthesiology, and psychiatry) between December 2023 and March 2024. House officers who were involved in primary care postings at nearby healthcare clinics were excluded, as were those from the medical department (because the head of the department did not grant permission).

Based on a study in Malaysia that reported the prevalence of anxiety among house officers as 33.7%,1 the estimated number of participants needed was 135, assuming a 5% margin of error and a 20% attrition rate. Convenience sampling was used.

House officers were approached during continuous medical education sessions. Those who consented to participate were given a QR code to access a questionnaire. Data recorded included sociodemographic profiles and environmental/work-related variables. Participants were asked to rate their levels of psychological flexibility and anxiety, as well as their perceived factors for anxiety (based on previous study findings2-4).

Psychological flexibility was assessed using the seven- item Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II).12 Each item is rated on a seven-point Likert scale from ‘never true’ to ‘always true’. Total scores range from 7 to 49; higher scores indicate less psychological flexibility. The Malay version of the AAQ-II has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 among non-clinical samples, with good reliability and validity,13 comparable with the 0.84 for the original AAQ-II.14 The cut-off scores of 24 to 28 are associated with depression and anxiety.15

Presence of anxiety over the previous 2 weeks was assessed using the seven-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale. Each item is rated on a four-point Likert scale from ‘not at all’ to ‘nearly every day’. Total scores range from 0 to 21; higher scores indicate more severe anxiety. A cut-off score of 8 has 92% sensitivity and 76% specificity in identifying clinically relevant anxiety.16

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Windows version 29.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States). A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data distributions were tested for normality. Non-parametric distributed data were presented as median (interquartile range). Participants with and without anxiety were compared using the independent t test for continuous variables or the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Simple logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine whether any significant variables were associated with anxiety. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to determine predictors for anxiety.

Results

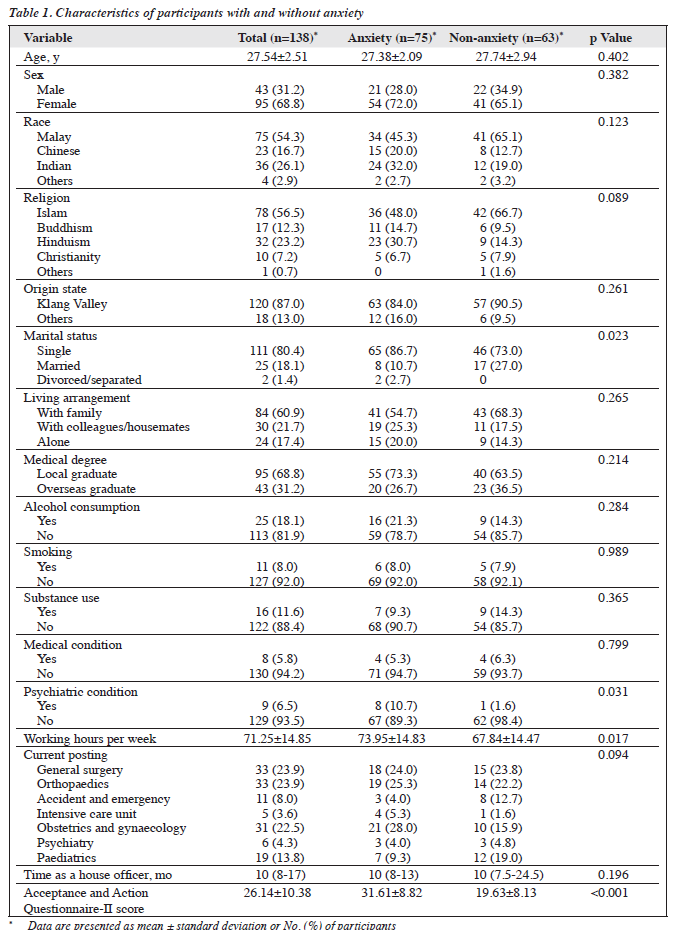

In total, 43 male and 95 female participants (mean age, 27.5 years) were included in the analysis (Table 1). Of the 138 participants, 75 (54.3%) were classified as having anxiety based on their GAD-7 scores. The anxiety and non-anxiety groups were comparable in terms of baseline characteristics, except for marital status (p=0.023). Participants with anxiety were more likely to have a psychiatric condition (10.7% vs 1.6%, p=0.031), work more hours per week (73.95 vs 67.84, p=0.017), and have higher AAQ-II scores (31.61 vs 19.63, p<0.001).

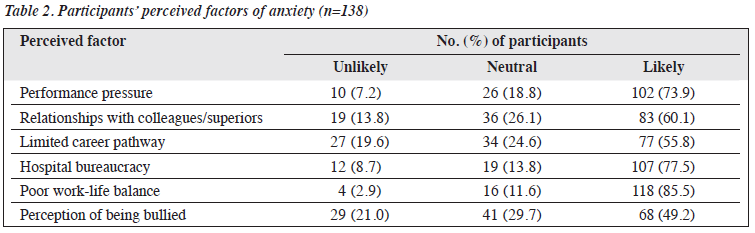

Common factors that the house officers perceived to be associated with anxiety included poor work-life balance (85.5%), hospital bureaucracy (77.5%), and performance pressure (73.9%) [Table 2]. Predictors for anxiety were the AAQ-II score (adjusted odds ratio=1.19, p<0.001) and working hours per week (adjusted odds ratio=1.04, p=0.034), after adjustment for sex, marital status, and psychiatric condition (Table 3).

Discussion

The prevalence of anxiety among house officers in our hospital was 54.3%, which is higher than the 33.7% among house officers in Malaysia during the COVID-19 pandemic and the 39.9% before the pandemic.5 However, it was consistent with other studies for house officers in teaching hospitals, with the prevalence ranging from 50% to 60%.2,19 The prevalence of anxiety among the general population in Selangor, Malaysia was only 8.2%.20

Although marital status differed significantly between participants with and without anxiety, marital status is not correlated with anxiety among Malaysian house officers,2 consistent with other studies involving healthcare workers. However, marriage does appear to be a protective factor against psychological distress,21 whereas being single can predispose people to anxiety.22 This can be explained by the positive effect of social support in marriages.23 Nevertheless, marital status is context-dependent and influenced by cultural and societal norms, with varying exposure to stressors and mental health risks being associated with different marital statuses.24

Anxiety is a common comorbidity in mental health conditions. However, the present study showed no significant associations between anxiety and medical history, substance use, smoking, or alcohol consumption.

The working hours among house officers were approximately 71 hours per week, consistent with the Malaysian Graduate Medical Officer Flexi Timetable system, which stipulates that house officers should work 65 to 75 hours per week.25 Each department has flexibility as long as it adheres to the initial framework. Notably, participants with anxiety had significantly longer working hours per week, consistent with a study of junior doctors in Australia that found associations between poor mental health outcomes and working ≥50 hours per week.26 Long working hours are also factor in mental health issues among the general population.27

Seniority in housemanship is not associated with anxiety.2,28 However, a study in West Malaysia reported that working experience was a protective factor for anxiety among house officers, probably owing to the increased coping experience with the tasks and duties.3

Most house officers reported that poor work-life balance was the primary cause of anxiety, followed by hospital bureaucracy and performance pressure. Work-life balance is the leading cause of stress.4 Anxiety is associated with imbalances between work effort, job demands, and home-related stress,29 which are components of work-life balance. Additionally, relationships with colleagues and superiors were also a common cause of anxiety, consistent with findings from a similar population.30

The mean score for psychological flexibility among house officers was 26.14, which was higher than that in other studies involving medical students and early- career professionals.10,30 Participants with anxiety had less psychological flexibility and longer working hours per week, consistent with findings of other studies.31-36 Psychological inflexibility is associated with poor mental health outcomes.37 High job demands and the need for rapid decision making can exacerbate feelings of anxiety when coupled with an inflexible capacity to adapt, accept, and change accordingly. Work-related stressors can affect the mental health of junior doctors; extended shifts and the pressure of life-or-death decisions can affect the wellbeing of practitioners.

Despite multiple interventions aimed at reducing working hours, stakeholders should ensure effective implementation of these interventions. There is still a gap in enhancing support systems that foster adaptive coping mechanisms and psychological resilience among house officers. Our findings suggest incorporating an acceptance and commitment therapy–based programme into housemanship to cultivate a flexible attitude toward challenging psychological events. Additionally, the AAQ-II can serve as a screening tool to identify individuals with high psychological inflexibility, allowing for early intervention.

There is a need to reassess work schedules to balance professional demands and wellbeing. Efforts have been made to enhance working conditions for junior doctors. For example, the European Working Time Directive limits doctors to a maximum of 48 working hours per week. However, any adjustments to working hours must not compromise the training to acquire sufficient knowledge. The challenge lies in determining the optimal balance. Longitudinal studies could shed light on the long-term impact of working hours on anxiety among house officers, potentially guiding policy changes in the healthcare sector.

The present study has several limitations. Convenience sampling was used, and thus participants were not randomly chosen; the sample may therefore not be representative of the population being studied. The use of self-report questionnaires is subject to recall bias and reporting bias. The cross-sectional design can identify associations only, not causal relationships. Data were collected from a single hospital and thus the generalisability of our findings may be limited, although Hospital Tengku Ampuan Rahimah is one of the busiest hospitals in Malaysia. Other factors associated with mental wellbeing such as sleep and fatigue,38 burnout,39 coping styles,5,40 and personality traits that may be confounders were not assessed. Given these limitations, the results should be interpreted with caution. Future research should aim at understanding the role of psychological inflexibility in anxiety among house officers.

Conclusion

Psychological inflexibility and excessive working hours are predictors for anxiety among house officers in a hospital in Malaysia. Institutional changes and individual-level interventions could lead to a healthier, more effective workforce.

Contributors

All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding / support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Faculty Ethics Review Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA (reference: 100 - FPR (PT.9/19) (FERC-02-23-02)) and registered under the National Medical Research Register (reference: 23-00833-ROY). The participants were treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The participants provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures and for publication.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the director and heads of departments and the Clinical Research Unit at Hospital Tengku Ampuan Rahimah, Klang, Selangor for their valuable cooperation.

References

- Lim YS, Abu Nowajish S, Amin Z, Anbarasan U, Lim UKG, Pinto J. Siew LY. Mental health of house officers during COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. ASEAN J Psychiatry 2022;23:1-12.

- Tan SM, Jong SC, Chan LF, et al. Physician, heal thyself: the paradox of anxiety amongst house officers and work in a teaching hospital. Asia Pac Psychiatry 2013;5 Suppl 1:74-81.

- Shahruddin SA, Saseedaran P, Salleh AD, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of stress, anxiety and depression among house officers in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah. Educ Med J 2016;8:31-40.

- Gopalakrishnan V, Umabalan T, Affan M, Zamri AA, Kamal A, Sandheep S. Stress perceived by houseman in a hospital in northern Malaysia. Med J Malaysia 2016;71:8-11.

- Ismail M, Lee KY, Sutrisno Tanjung A, et al. The prevalence of psychological distress and its association with coping strategies among medical interns in Malaysia: a national-level cross-sectional study. Asia Pac Psychiatry 2020;13:e12417.

- Stange JP, Alloy LB, Fresco DM. Inflexibility as a vulnerability to depression: a systematic qualitative review. Clin Psychol (New York) 2017;24:245-76.

- Rottenberg J, Yoon S. Whither inflexibility in depression? Clin Psychol Sci Pract 2017;24:277-80.

- Burton CL, Bonanno GA. Measuring ability to enhance and suppress emotional expression: the Flexible Regulation of Emotional Expression (FREE) Scale. Psychol Assess 2016;28:929-41.

- McCracken LM, Badinlou F, Buhrman M, Brocki KC. The role of psychological flexibility in the context of COVID-19: associations with depression, anxiety, and insomnia. J Contextual Behav Sci 2021;19:28-35.

- Bonilla-Sierra P, Manrique-G A, Hidalgo-Andrade P, Ruisoto P. Psychological inflexibility and loneliness mediate the impact of stress on anxiety and depression symptoms in healthcare students and early-career professionals during COVID-19. Front Psychol 2021;12:729171.

- Ganasegeran K, Perianayagam W, Manaf RA, Jadoo SA, Al-Dubai SA. Patient satisfaction in Malaysia’s busiest outpatient medical care. ScientificWorldJournal 2015;2015:714754.

- Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, et al. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: a revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav Ther 2011;42:676-88.

- Shari NI, Zainal NZ, Guan NC, Ahmad Sabki Z, Yahaya NA. Psychometric properties of the acceptance and action questionnaire (AAQ II) Malay version in cancer patients. PLoS One 2019;14:e0212788.

- Mohd Bahar FH, Mohd Kassim MA, Pang NTP, Koh EBY, Kamu A, Ho CM. Malay version of Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II): a reliability and validity analysis in non-clinical samples. IIUM 2022;21:67-75.

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: the Process and Practice of Mindful Change: Guilford Press; 2011.

- Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, McMillan D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016;39:24-31.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092-7.

- Sidik SM, Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F. Validation of the GAD-7 (Malay version) among women attending a primary care clinic in

Malaysia. J Prim Health Care 2012;4:5-11.

- Yeoh CM, Thong KS, Seed HF, Nur Iwana AT, Maruzairi H. Psychological morbidities amongst house officers in Sarawak General

Hospital Kuching. Med J Malaysia 2019;74:307-11.

- Kader Maideen SF, Mohd Sidik S, Rampal L, Mukhtar F. Prevalence, associated factors and predictors of anxiety: a community survey in Selangor, Malaysia. BMC Psychiatry 2015;15:262.

- Farahmand S, Karimialavijeh E, Vahedi HS, Jahanshir A. Emergency medicine as a growing career in Iran: an Internet-based survey. World J Emerg Med 2016;7:196-202.

- Cheung T, Yip PS. Depression, anxiety and symptoms of stress among Hong Kong nurses: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:11072-100.

- Fincham FD, Beach SRH. Marriage in the new millennium: a decade in review. J Marriage Fam 2010;72:630-49.

- Ta-Johnson VP, Gesselman AN, Perry BL, Fisher HE, Garcia JR. Stress of singlehood: marital status, domain-specific stress, and anxiety in a national US sample. J Soc Clin Psychol 2017;36:461-85.

- Chua Y, Lim MY, Mohd Shafiaai MSF, Tan Y. Policy Brief POL-2021-01. Improving Houseman Training in Malaysia. Malaysian Medics International: 2021.

- Petrie K, Crawford J, Shand F, Harvey SB. Workplace stress, common mental disorder and suicidal ideation in junior doctors. Intern Med J 2021;51:1074-80.

- Bannai A, Tamakoshi A. The association between long working hours and health: a systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Scand J Work Environ Health 2014;40:5-18.

- Henning MA, Sollers J, Strom JM, et al. Junior doctors in their first year: mental health, quality of life, burnout and heart rate variability. Perspect Med Educ 2014;3:136-43.

- Sen S, Kranzler HR, Krystal JH, et al. A prospective cohort study investigating factors associated with depression during medical internship. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:557-65.

- Al-Dubai SA, Ganasegeran K, Perianayagam W, Rampal KG. Emotional burnout, perceived sources of job stress, professional fulfillment, and engagement among medical residents in Malaysia. ScientificWorldJournal 2013;2013:137620.

- Szarko AJ, Ramona H, Smith GS, et al. Impact of acceptance and commitment training on psychological flexibility and burnout in medical education. J Contextual Behav Sci 2022;23:190-9.

- Bluett EJ, Homan KJ, Morrison KL, Levin ME, Twohig MP. Acceptance and commitment therapy for anxiety and OCD spectrum disorders: an empirical review. J Anxiety Disord 2014;28:612-24.

- Masuda A, Mandavia A, Tully EC. The role of psychological inflexibility and mindfulness in somatization, depression, and anxiety among Asian Americans in the United States. Asian Am J Psychol 2013;5:230-6.

- Gilbert KE, Tonge NA, Thompson RJ. Associations between depression, anxious arousal and manifestations of psychological inflexibility. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2019;62:88-96.

- Tavakoli N, Broyles A, Reid EK, Sandoval JR, Correa-Fernández V. Psychological inflexibility as it relates to stress, worry, generalized anxiety, and somatization in an ethnically diverse sample of college students. J Contextual Behav Sci 2019;11:1-5.

- Uğur E, Kaya Ç, Tanhan A. Psychological inflexibility mediates the relationship between fear of negative evaluation and psychological vulnerability. Curr Psychol 2021;40:4265-77.

- Cicek I, Tanhan A, Bulus M. Psychological inflexibility predicts depression and anxiety during COVID-19 Pandemic. i-Manag J Educ Psychology 2021;15:11-24.

- Afonso P, Fonseca M, Pires JF. Impact of working hours on sleep and mental health. Occup Med (Lond) 2017;67:377-82.

- Lim LEC, Heng GMYT, Chan YH, et al. Factors associated with burnout among healthcare workers in a Singaporean hospital during the post-COVID era. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2024;34:58-64.

- Shao R, He P, Ling B, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety and correlations between depression, anxiety, family functioning, social support and coping styles among Chinese medical students. BMC Psychol 2020;8:38.