East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2023;33:114-9 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2342

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Abstract

Background: Suicidal behaviour can be influenced by attitudes towards suicide and psychological distress. This study aimed to investigate the associations between psychological distress, attitudes towards suicide, and suicidal behaviour and to determine the prevalence of suicidal behaviour among students of a public university in East Malaysia.

Methods: A total of 521 students from a public university in East Malaysia were asked to complete the Malay versions of the Suicidal Behaviour Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R), the Attitudes Towards Suicide Scale, and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale.

Results: 197 women and 290 men (mean age, 19.13 years) completed the questionnaires, giving a response rate of 93.4%. The prevalence of high-risk suicidal behaviour (SBQ-R score ≥7) was 23.8%. Suicidal behaviour was positively associated with psychological distress and favourable attitudes towards suicide, and negatively associated with unfavourable attitudes towards suicide. Predictors for suicidal behaviour were psychological distress and favourable attitudes towards suicide (‘the ability to understand and accept suicide’).

Conclusion: The prevalence of suicidal behaviour is high among students in a public university in East Malaysia. Services and education for mental health awareness and screening for early detection and intervention of psychological distress should be provided to university students. Implementation of suicide awareness policies and suicide prevention training is crucial.

Mohd Nur Shakir Bin Kamaruddin, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh Campus, Selangor Branch, Selangor, Malaysia

Nurul Azreen Binti Hashim, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh Campus, Selangor Branch, Selangor, Malaysia

Salina Binti Mohamed, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh Campus, Selangor Branch, Selangor, Malaysia

Zahir Izuan Bin Azhari, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh Campus, Selangor Branch, Selangor, Malaysia

Address for correspondence: Dr Nurul Azreen Binti Hashim, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh Campus, Selangor Branch, 47000 Jalan Hospital, Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia. Email: azreen@uitm.edu.my

Submitted: 14 August 2023; Accepted: 16 November 2023

Introduction

Suicidal behaviour can affect individuals of all ages, sexes, and backgrounds. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 703 000 people worldwide die by suicide every year, and the suicide mortality rate in 2019 was 9.0 per 100 000 people.1 Suicide was the fourth-highest cause of death among young people aged 15 to 29 years.2 However, many cases are unreported owing to misclassification (eg, recorded as accidents) or underreported owing to their sensitive nature.

Many individuals attempt suicide or have suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation and behaviours are a unidimensional construct, with passive ideation, active intent, and behaviour existing along a continuum. Young adults are at the highest risk of suicidal behaviour.3,4 The risk factors for suicidal behaviour are female sex, younger age, fewer years of formal education, prior mental disorder, earlier age of onset of suicidal behaviour, physical health, illicit substance dependence, alcohol dependence, personality disorder, loneliness, hopelessness, and adverse life events.3,5 Protective factors for suicidal behaviour include strong religious affiliation and orthodoxy, family cohesion and support, and good coping skills.3,5

Attitudes towards suicide also exist along a continuum, ranging from a more accepting and permissive attitude that understands suicide under some circumstances without approving of it to condemnation of suicide under any circumstances.6 Suicide is considered a sin, and attitudes towards it are negative. However, attitudes towards suicide among young people are more agreeable nowadays.7 Favourable or permissive attitudes towards suicide are positively associated with suicidal behaviour, whereas unfavourable or rejecting attitudes towards suicide are negatively associated with suicidal behaviour.8-10

The prevalence of psychological distress (depression, anxiety, and stress) is high among undergraduate students,11,12 and psychological distress is positively associated with suicidal behaviour.13-15 In Malaysia, psychological distress and permissive attitudes towards suicide have been found to affect suicidal behaviour.16 In West Malaysia, religious affiliation, psychological distress, family support, and a permissive attitude towards suicide affect suicidal behaviour.8,17-19 This study aimed to determine the associations between suicidal behaviour, psychological distress, and attitudes towards suicide, as well as the prevalence of suicidal behaviour among university students in East Malaysia.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted among students attending a public university in East Malaysia between November and December 2022. Based on a reported 7% prevalence of suicide in a similar population20 and a potential non-response rate of 20%, a sample size of 521 was required to achieve 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error. The inclusion criteria were being undergraduate students at the university, age ≥18 years, and able to communicate in Bahasa Melayu. Using convenience sampling, every fourth student was randomly selected to ask to complete the Malay versions of the Suicidal Behaviour Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R), the Attitudes Towards Suicide Scale, and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale - 21 items.

The SBQ-R consists of four items that measure dimensions of suicidality to screen for suicide risk. The items include lifetime suicidal ideation and/or suicide attempts, the frequency of suicidal ideation over the past 12 months, threats of suicide, and the likelihood of future suicidal behaviour. Suicidal behaviour is dichotomised as high or low suicidal behaviour; the cut-off score for high suicidal behaviour is ≥7. The SBQ-R has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76-0.88) and good concurrent validity (r = 0.61-0.93).8 The Malay version has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.65 to 0.80.8,20

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale - 21 items measures psychological distress in terms of depression, anxiety, and stress. It has high reliability and validity, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.74 to 0.93.21,22 The Malay version has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84 to 0.86.23

The Attitudes Towards Suicide Scale comprises 37 items in 10 subscales; each item is measured in a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate more positive attitudes towards suicide.6 The Cronbach’s alpha of the subscales ranges from 0.35 to 0.84.6 The Malay version has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.72 overall and 0.57 to 0.76 for the subscales; the four factors with the highest loading were ‘ability to understand and accept suicide’, ‘believability of suicidal threats’, ‘judgement and ability to help’, and ‘acceptability of assisted suicide’.24

Data were analysed using SPSS (Windows version 23.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], USA). Factors associated with suicidal behaviour were determined using the Pearson Chi-squared test. Independent factors associated with suicidal behaviour were determined using both simple and multiple logistic regression.

Results

Of 521 students included, 197 women and 290 men (mean age, 19.13 years) completed the questionnaires, giving a response rate of 93.4% (Table 1). The prevalence of high- risk suicidal behaviour (SBQ-R score ≥7) was 23.8%. The prevalence was highest among those of the Kadazan-Dusun- Murut ethnicity (29.1%), followed by Malay (25.8%), other ethnicities (22.3%), and Bajau (11.4%); it was also higher in Christians than in Muslims (27.8% vs 22.2%), in females than males (33.0% vs 17.6%), and in those of the middle 40% income group than in those of the bottom 40% income group or top 20% income group (24.3% vs 23.9% vs 20.0%).

Psychological distress was extremely severe in 17 (3.5%) participants, moderate to severe in 115 (23.6%) participants, and normal to mild in 355 (72.9%) participants. Anxiety was extremely severe in 116 (23.8%) participants, moderate to severe in 143 (29.3%) participants, and normal to mild in 228 (46.7%) participants. Depression was extremely severe in 32 (6.6%) participants, moderate to severe in 133 (27.3%) participants, and normal to mild in 322 (66.1%) participants.

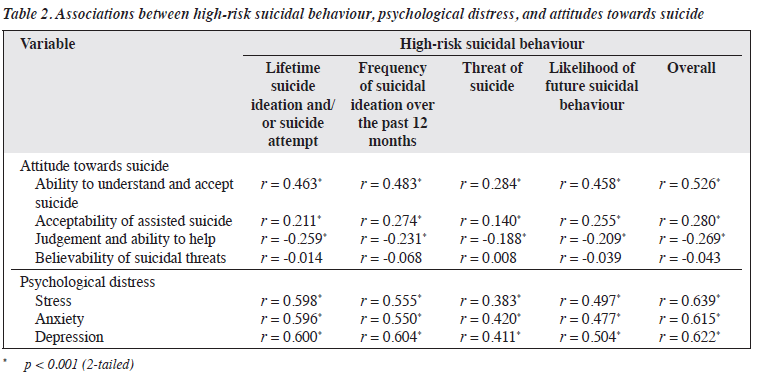

High-risk suicidal behaviour was positively associated with favourable attitudes towards suicide (‘ability to understand and accept suicide’ and ‘acceptability of assisted suicide’) and psychological distress (stress, anxiety, and depression) and negatively associated with unfavourable attitudes towards suicide (‘judgement and ability to help’) [all p < 0.01, Table 2].

In simple logistic regression analysis, high-risk suicidal behaviour was independently associated with female sex (odds ratio [OR] = 2.31, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.51-3.52, p < 0.001), ‘ability to understand and accept suicide’ (OR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.20-1.33, p < 0.001), ‘judgement and ability to help’ (OR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.73-0.87, p < 0.001), ‘acceptability of assisted suicide’ (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.12-1.37, p < 0.001), stress (OR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.16-1.25, p < 0.001), anxiety (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.13-1.20, p < 0.001), and depression (OR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.14-1.22, p < 0.001) [Table 3].

In multiple logistic regression analysis, high-risk suicidal behaviour was independently associated with stress (adjusted OR = 2.84, 95% CI = 1.49-5.43, p = 0.002), depression (adjusted OR = 1.92, 95% CI = 1.09-3.38, p = 0.03), anxiety (adjusted OR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.16-3.03, p = 0.01), and permissive attitude towards suicide (‘ability to understand and accept suicide’) [adjusted OR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.05-1.22, p = 0.04] (Table 3).

Discussion

In the present study, 23.8% of students in a public university in East Malaysia reported high-risk suicidal behaviour, which is higher than the 7% reported in a study among college students in West Malaysia, which has a higher level of urbanicity.20 Rural areas have a higher prevalence of suicidal behaviour, compared with urban areas.25,26 Furthermore, 60.2% of participants were from low- income households, which is also associated with suicidal behaviour.27 The present study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic; since that time the prevalence of suicidal ideation has increased.28 Although 23.8% of participants reported high-risk suicidal behaviour, only 2.9% reported being diagnosed with a psychiatric illness. This may reflect a gap in psychiatry services or poor mental health literacy among undergraduate students in East Malaysia.29

Female participants had a higher prevalence of suicidal behaviour, consistent with findings in other studies.3,4,20,30 Psychological distress is more prevalent among females12,14,31 and is positively associated with suicidal behaviour.13-15 Possible reasons for this include hormonal changes and differing psychosocial stressors in females.32

Suicidal behaviour was found to be positively associated with favourable or permissive attitudes towards suicide and psychological distress and negatively associated with unfavourable or rejecting attitudes towards suicide, consistent with findings in other studies.8-10,16,33,34 Stress, anxiety, depression, and a permissive attitude towards suicide (‘ability to understand and accept suicide’) were predictors of suicidality, consistent with findings in other studies.13,15,31

Religion has been reported as a predictor of suicidality,35 but the present study did not find any such association. One possible explanation is that religious devotion or degree of religiosity is the actual variance for suicidal behaviour, rather than the type of religion. Religiosity refers to an individual’s appraisal of the meaning of life through religious beliefs, values, and practices. Strong religious affiliation is associated with a more rejecting attitude towards suicide and a lower prevalence of suicidal behaviour.8,19,36,37 People from similar religions differ significantly in their attitudes towards suicide and suicidal behaviour based on their levels of religiosity.38 Among Muslim countries, those with higher degrees of religiosity are less accepting of suicide and have lower suicidality.39 Strong religious devotion is a protective factor against suicidal behaviour.3,5

This study has several limitations. The cross- sectional design cannot infer causal relationships. Self-report questionnaires are prone to bias, and participants tend to underreport symptoms. For example, only 1% of participants reported drinking alcohol, but the Malaysia National Health and Morbidity Survey 2019 shows a much higher percentage, especially in East Malaysia.40 Another example is that 23.8% of participants reported high-risk suicidal behaviour, compared with only 7% in another study; this difference might be due to biases arising from self- report questionnaires. Additionally, mental health disorders were not assessed using DSM-5 or ICD-10 by a trained professional. In our university, 60.2% of students were from low-income households, and there were fewer students of Chinese and Indian ethnicities. Therefore, generalisation of our results to university students in West Malaysia may not be applicable. Future studies should include factors such as academic stress and pressure, social isolation, and family and relationship issues.

Conclusion

The prevalence of suicidal behaviour is high among students in a public university in East Malaysia. Predictors for suicidal behaviour were psychological distress and favourable attitudes towards suicide (‘the ability to understand and accept suicide’). Services and education for mental health awareness and screening for early detection and intervention of psychological distress should be provided to university students. Attitudes towards suicide are multidimensional, and not all influence suicidal behaviour. Implementation of suicide awareness policies and suicide prevention training is crucial.

Contributors

All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding / Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Universiti Teknologi MARA (reference: 600-TNCPI (5/1/6), REC/06/2022 (FB/33)).

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide worldwide in 2019: global health estimates. Geneva. 2021. Accessed 14 August 2023. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1350975/retrieve

- Bilsen J. Suicide and youth: risk factors. Front Psychiatry 2018;9:540 Crossref.

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry 2008;192:98-105. Crossref

- Maniam T, Marhani M, Firdaus M, et al. Risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts in Malaysia: results of an epidemiological survey. Compr Psychiatry 2014;55(Suppl 1):S121-5. Crossref

- Gearing RE, Alonzo D. Religion and suicide: new findings. J Relig Health 2018;57:2478-99. Crossref

- Renberg ES, Hjelmeland H, Koposov R. Building models for the relationship between attitudes toward suicide and suicidal behavior: based on data from general population surveys in Sweden, Norway, and Russia. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2008;38:661-75. Crossref

- Zemaitiene N, Zaborskis A. Suicidal tendencies and attitude towards freedom to choose suicide among Lithuanian schoolchildren: results from three cross-sectional studies in 1994, 1998, and 2002. BMC Public Health 2005;5:83. Crossref

- Foo XY, Alwi MN, Ismail SI, Ibrahim N, Osman ZJ. Religious commitment, attitudes toward suicide, and suicidal behaviors among college students of different ethnic and religious groups in Malaysia. J Relig Health 2014;53:731-46. Crossref

- Kim MJ, Lee H, Shin D, et al. Effect of attitude toward suicide on suicidal behavior: based on the Korea National Suicide Survey. Psychiatry Investig 2022;19:427-34. Crossref

- Otsuka H, Anamizu S, Fujiwara S, et al. Japanese young adults’ attitudes toward suicide and its influencing factors. Asian J Psychiatr 2020;47:101831. Crossref

- Shao R, He P, Ling B, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety and correlations between depression, anxiety, family functioning, social support and coping styles among Chinese medical students. BMC Psychol 2020;8:38. Crossref

- Islam MA, Low WY, Tong WT, Wan Yuen CC, Abdullah A. Factors associated with depression among university students in Malaysia: a cross-sectional Study. KnE Life Sci 2018;4:415. Crossref

- Wang YH, Shi ZT, Luo QY. Association of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among university students in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6476. Crossref

- Casey SM, Varela A, Marriott JP, Coleman CM, Harlow BL. The influence of diagnosed mental health conditions and symptoms of depression and/or anxiety on suicide ideation, plan, and attempt among college students: findings from the Healthy Minds Study, 2018-2019. J Affect Disord 2022;298:464-71. Crossref

- Asfaw H, Yigzaw N, Yohannis Z, Fekadu G, Alemayehu Y. Prevalence and associated factors of suicidal ideation and attempt among undergraduate medical students of Haramaya University, Ethiopia. A cross sectional study. PLoS One 2020;15:e0236398. Crossref

- Tan L, Yang QH, Chen JL, Zou HX, Xia TS, Liu Y. The potential role of attitudes towards suicide between mental health status and suicidal ideation among Chinese children and adolescents. Child Care Health Dev 2017;43:725-32. Crossref

- Ibrahim N, Amit N, Che Din N, Ong HC. Gender differences and psychological factors associated with suicidal ideation among youth in Malaysia. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2017;10:129-35. Crossref

- Ibrahim N, Che Din N, Ahmad M, et al. The role of social support and spiritual wellbeing in predicting suicidal ideation among marginalized adolescents in Malaysia. BMC Public Health 2019;19(Suppl 4):553. Crossref

- Ooi MY, Rabbani M, Yahya AN, Siau CS. The relationship between religious orientation, coping strategies and suicidal behaviour. Omega (Westport) 2023;86:1312-28. Crossref

- Tin TS, Sidik SM, Rampal L, Ibrahim N. Prevalence and predictors of suicidality among medical students in a public university. Med J Malaysia 2015;70:1-5.

- Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 2005;44:227-39. Crossref

- Oei TPS, Sawang S, Goh YW, Mukhtar F. Using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21) across cultures. Int J Psychol 2013;48:1018-29. Crossref

- Bin Nordin R, Kaur A, Soni T, Por LK, Miranda S. Construct validity and internal consistency reliability of the Malay version of the 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (Malay-DASS-21) among male outpatient clinic attendees in Johor. Med J Malaysia 2017;72:264-70.

- Siau CS, Wee LH, Ibrahim N, Visvalingam U, Wahab S. Cross- cultural adaptation and validation of the attitudes toward suicide questionnaire among healthcare personnel in Malaysia. Inquiry 2017;54:46958017707295. Crossref

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. Household Income & Basic Amenities Survey Report 2019. 2020:5-8.

- Yang LS, Zhang ZH, Sun L, Sun YH, Ye DQ. Prevalence of suicide attempts among college students in China: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0116303. Crossref

- Raschke N, Mohsenpour A, Aschentrup L, Fischer F, Wrona KJ. Socioeconomic factors associated with suicidal behaviors in South Korea: systematic review on the current state of evidence. BMC Public Health 2022;22:129. Crossref

- Shanmugam H, Juhari JA, Nair P, Ken CS, Guan N. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in Malaysia: a single thread of hope. Malaysian J Psychiatry 2020;29:78-84.

- Pang NTP, Shoesmith WD. The interpretation of depressive symptoms in urban and rural areas in Sabah, Malaysia. ASEAN J Psychiatry 2016;17:42-53.

- Li ZZ, Li YM, Lei XY, et al. Prevalence of suicidal ideation in Chinese college students: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e104368. Crossref

- Demenech LM, Oliveira AT, Neiva-Silva L, Dumith SC. Prevalence of anxiety, depression and suicidal behaviors among Brazilian undergraduate students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2021;282:147-59. Crossref

- Pope CJ, Oinonen K, Mazmanian D, Stone S. The hormonal sensitivity hypothesis: a review and new findings. Med Hypotheses 2017;102:69-77. Crossref

- Milligan M, See HP, Beck HP, Crawford S, Doss K. Suicidality: college students’ attitudes and behaviours in Malaysia. Int J Asia Pac Stud 2022;18:151-67. Crossref

- Eskin M, Kujan O, Voracek M, et al. Cross-national comparisons of attitudes towards suicide and suicidal persons in university students from 12 countries. Scand J Psychol 2016;57:554-63. Crossref

- Lew B, Kõlves K, Zhang J, et al. Religious affiliation and suicidality among college students in China: a cross-sectional study across six provinces. PLoS One 2021;16:e0251698. Crossref

- Saiz J, Ayllón-Alonso E, Sánchez-Iglesias I, Chopra D, Mills PJ. Religiosity and suicide: a large-scale international and individual analysis considering the effects of different religious beliefs. J Relig Health 2021;60:2503-26. Crossref

- Hamdan S, Peterseil-Yaul T. Exploring the psychiatric and social risk factors contributing to suicidal behaviors in religious young adults. Psychiatry Res 2020;287:112449. Crossref

- Boyd KA, Chung H. Opinions toward suicide: cross-national evaluation of cultural and religious effects on individuals. Soc Sci Res 2012;41:1565-80. Crossref

- Eskin M, Baydar N, El-Nayal M, et al. Associations of religiosity, attitudes towards suicide and religious coping with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in 11 Muslim countries. Soc Sci Med 2020;265:113390. Crossref

- Institute for Public Health, Ministry of Health Malaysia. National Health and Morbidity Survey 2019: Non-Communicable Diseases: Risk Factors and Other Health Problems. Accessed 14 August 2023. Available from: https://iku.moh.gov.my/images/IKU/Document/ REPORT/NHMS2019/Report_NHMS2019-NCD_v2.pdf